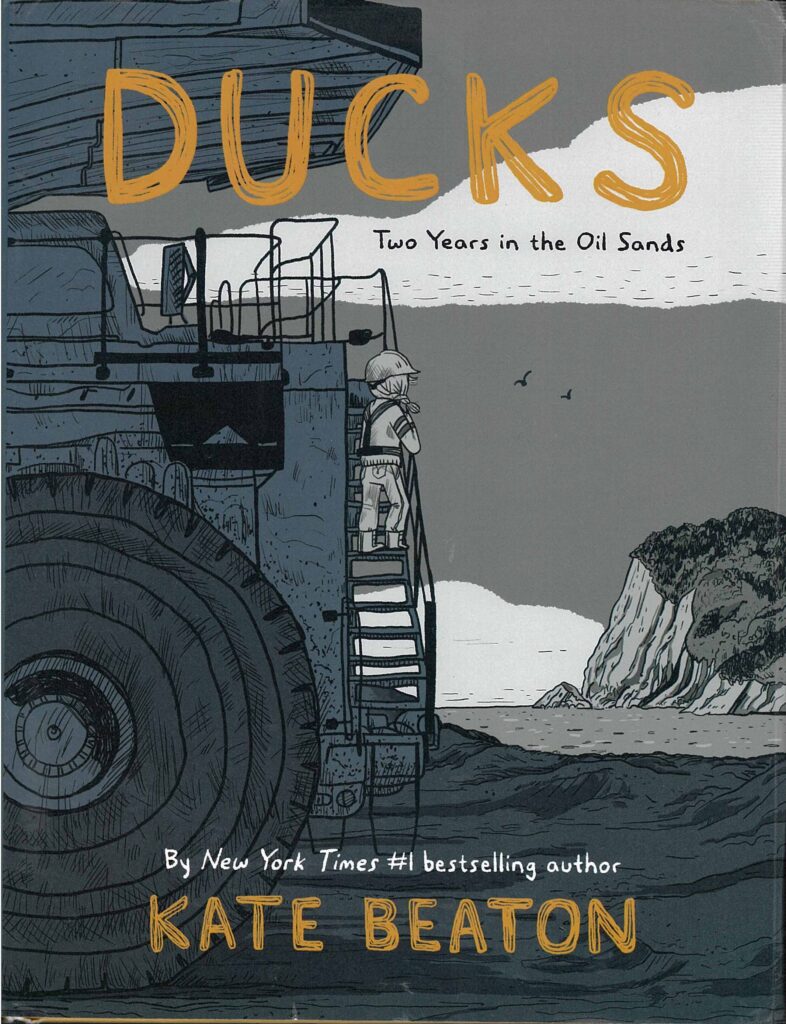

“Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands.” Written and illustrated by Kate Beaton. Drawn and Quarterly: $39.95. September 2022, 436 pages.

Adult: salty language, drug references, sexual assault

Thanks to Fables Books, 215 South Main Street in downtown Goshen, Indiana, for providing Commons Comics with books to review.

Check Fables out online at www.fablesbooks.com, order over the phone at 574-534-1984, or email them at fablesbooks@gmail.com.

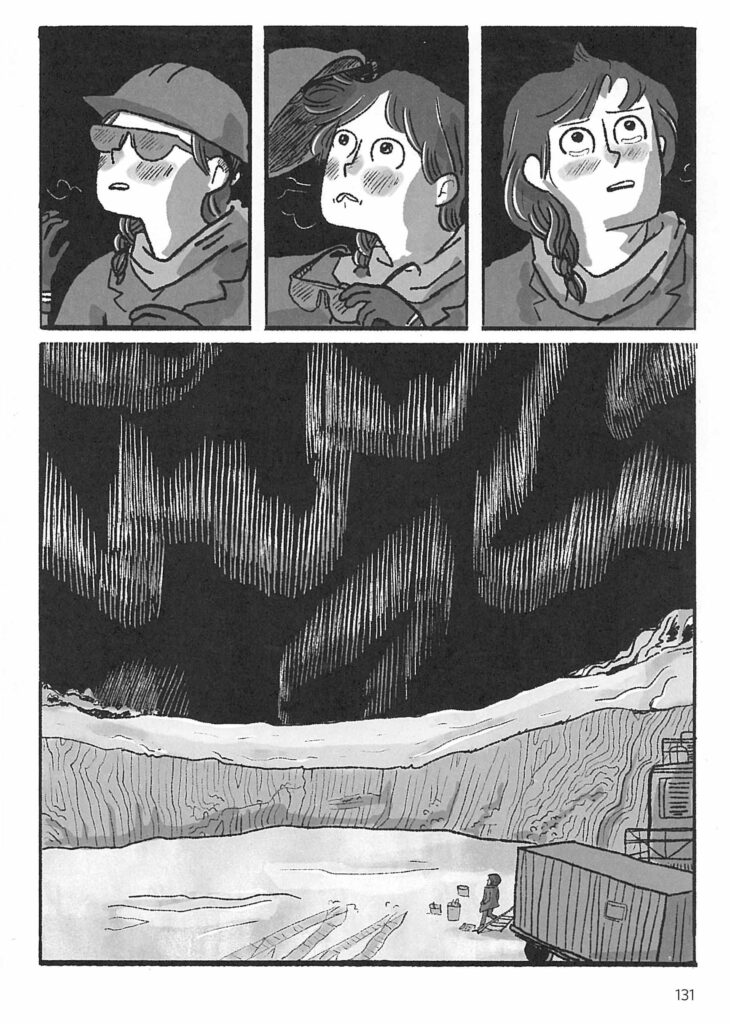

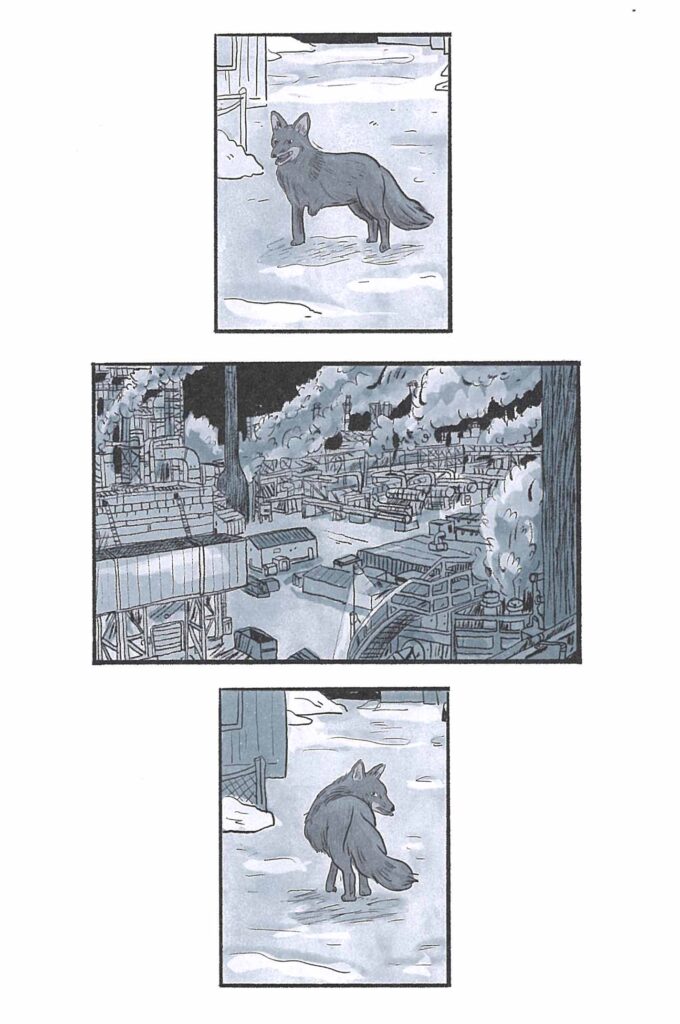

“Two Years in the Oil Sands,” the subtitle of Kate Beaton’s memoir, “Ducks,” makes it clear that Beaton’s time in this alien landscape will be finite: two years. What readers don’t know is just how difficult that time will be. But difficult doesn’t mean bereft of beauty:

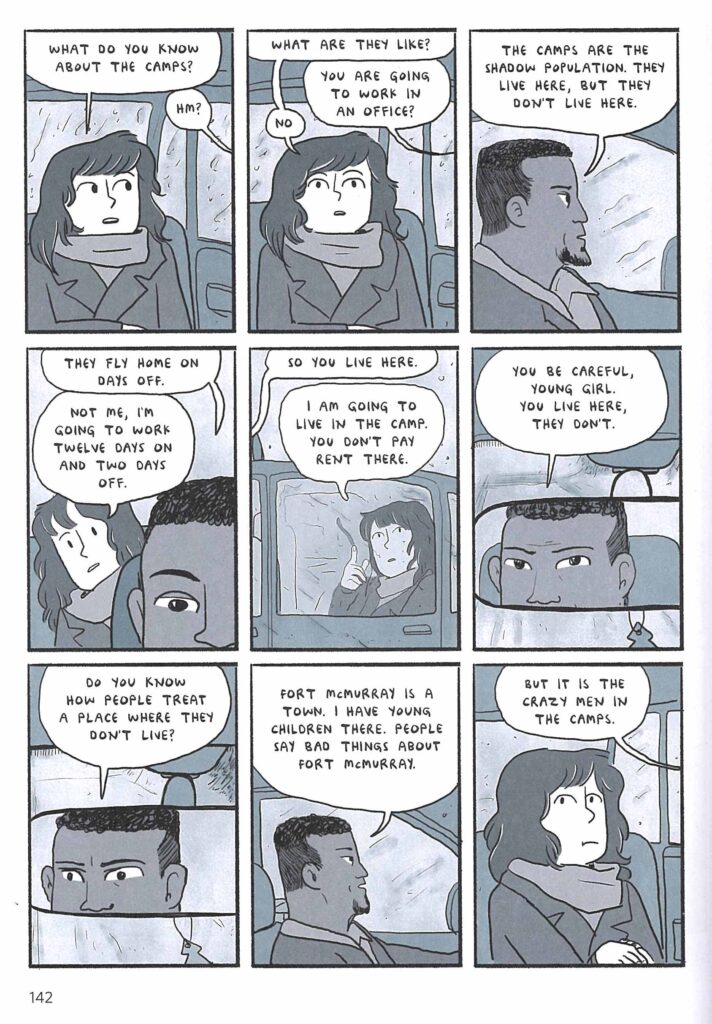

The oil sands occupy a region in Alberta, Canada, roughly the size of England, which has been scarred not only by toxic industrial oil extraction, but, as “Ducks” makes clear, by the toxic masculinity that feeds the oil corporations’ profit-driven culture. Especially at the higher-paying but more isolated camps, identities on the outskirts—bipoc, female, even creative—suffer not only ostracization, but violence. On the page below, a Somali taxi driver warns “Katie,” Beaton’s narrative self, who is transferring to a job with higher wages at a more remote camp:

Conversations can be difficult to convey effectively in comics: it takes expertise to trim the words, and to keep the visuals dynamic. Beaton is a pro, however, and makes this largely dialogue-driven book difficult to put down. She built her expertise with her webcomic “Hark, a Vagrant!” which enlivened Western literary and historical figures who also did a lot of talking. “Hark” brought to life characters from Richard III to Ida B. Wells, Edgar Allen Poe to Jane Austen, infusing their conversations with panel-driven punchlines. Beaton launched “Hark” in the early days of webcomics, during a brief midpoint break from her stint in the oil sands. Regularly creating and posting the strip when she returned to work in the sands after the hiatus proved a necessary lifeline to a more stable and livable world—and fanbase—outside of her bleak, cold, and often lonely day-to-day job.

After both print collections of “Hark” became bestsellers, Beaton moved into children’s books. The most beloved of those books, “The Princess and the Pony,” about a would-be warrior princess and her odd-looking, farting pony sidekick, has now been transformed into a television series, “Pinecone and Pony.”

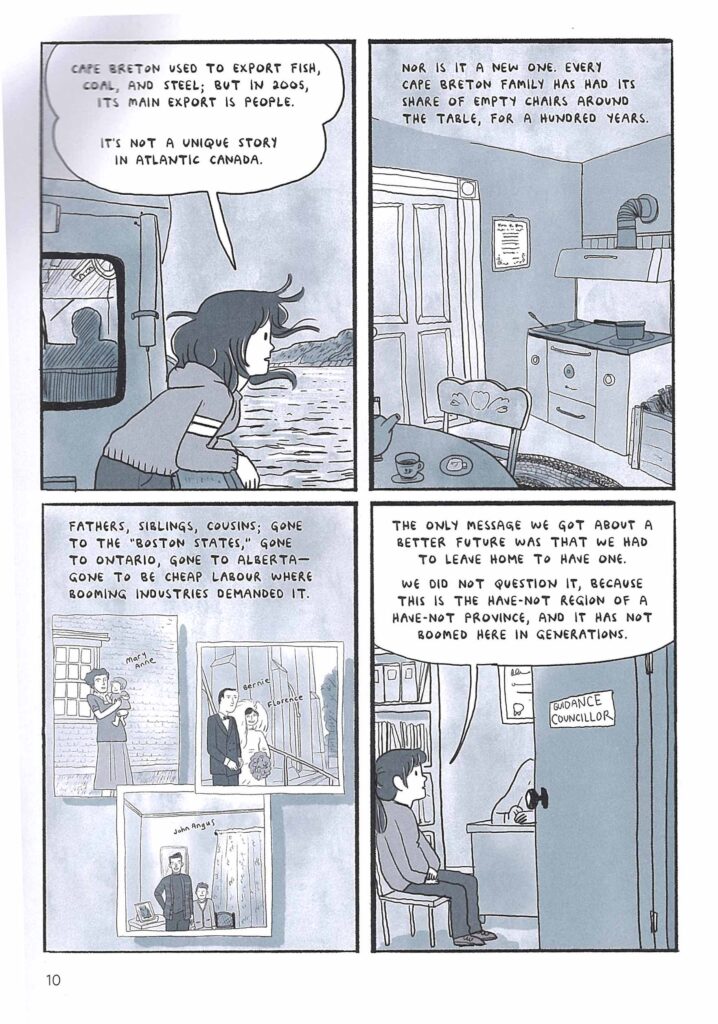

Stunning success story, right? In 2005, however, Beaton had just graduated with a degree in history and anthropology, heavy student debt, and no financially sustainable job prospects on or near Canada’s Cape Breton Island, where she grew up. She chose to join a long tradition of economically-motivated exodus from the region. As she has discussed in interviews, it seemed like the only option at the time, especially since Canada’s student loan repayment program wasn’t designed for artists’ wages. Today, thanks to remote connectivity options for creatives, Beaton lives blissfully in a Cape Breton farmhouse with her husband and two children. She was raised with the belief, however, that she would have to leave home to make her way in the world.

“Ducks” might at first seem like a drastic shift from the slapstick of “Hark, A Vagrant!” but this story had been bubbling in the back of Beaton’s mind for a long time: she knew it needed to be told. As she explained to “Wired” magazine, she became a bit like Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s crazed narrator in his 1798 poem, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”: “If I started talking about the oil sands to someone, I couldn’t stop, because there was no point at which I could be satisfied I’d explained it.” According to Beaton, her crack editors worked hard to trim her near-thousand-page rough draft to less than five hundred pages. If that sounds long to you, be forewarned: you will have a hard time putting this book down once you begin to read.

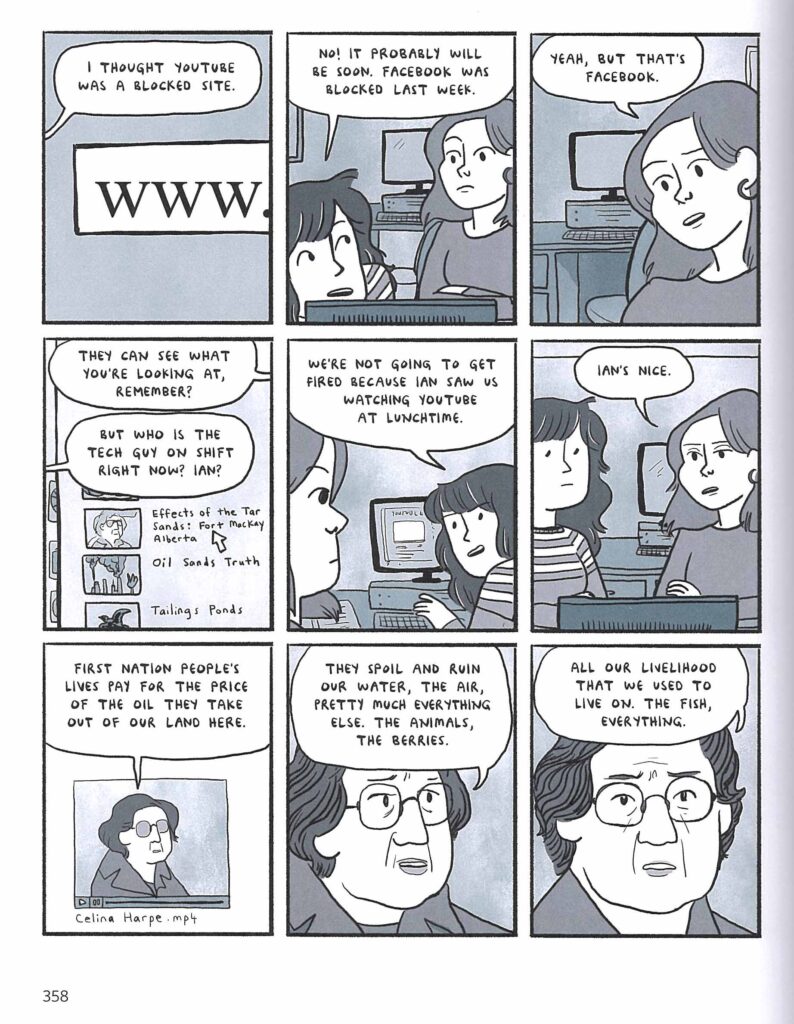

Beaton’s narrator begins the story naïve—almost literally wide-eyed—and ready to work as hard as necessary to pay off her loans and start the rest of her life. Readers are educated alongside her, gaining knowledge little by little about the environmental and human costs of the operations that fuel not only paychecks, but the national coffers. In these very early days of the internet, the extraction companies actively try to restrict outside information about the bubble within which Beaton and her coworkers are enclosed:

The First Nations woman in this video testimony is Celina Harpe, who has been living her whole life in Fort McKay, a town centered amidst multiple extraction sites. Harpe has been witnessing the rise of rare cancers and other health problems in Fort McKay and its surrounding area since the corporations first set up shop in the oil sands. She began to speak out after seeing more and more otherwise healthy people—especially young people—die.

You might expect flat-out rage or a diatribe in the face of such blatant injustice. Make no mistake: Beaton is clearly angry. Yet she has never been one to flatten a multi-dimensional story. She is also well aware that the best way to convince the people who haven’t already made up their minds is to let them decide for themselves. Beaton encourages readers to witness the pressure, struggles, and heartbreak that her co-workers deal with on a daily basis—and to note how few of them are lucky enough to have an exit strategy, like she does. As Beaton explained in an interview with “Fort McMurray Today,” a paper located smack in the middle of oil sands operations, “If you’re not involved in the industry, I feel the image is very distorted. . . . Most people associate it with . . . gigantic trucks and huge mines, but they rarely think about the human beings inside them.”

Beaton’s compassion for her co-workers doesn’t let them off the hook, however. The men working at these sites outnumber the women approximately 50 to 1, and readers witness Katie dealing with appalling harassment. She is barked at like a dog, repeatedly solicited for sex, and her body is discussed at length, within earshot, by the worst of her coworkers. These are the more harmless examples, because they don’t extend into physical contact or violence.

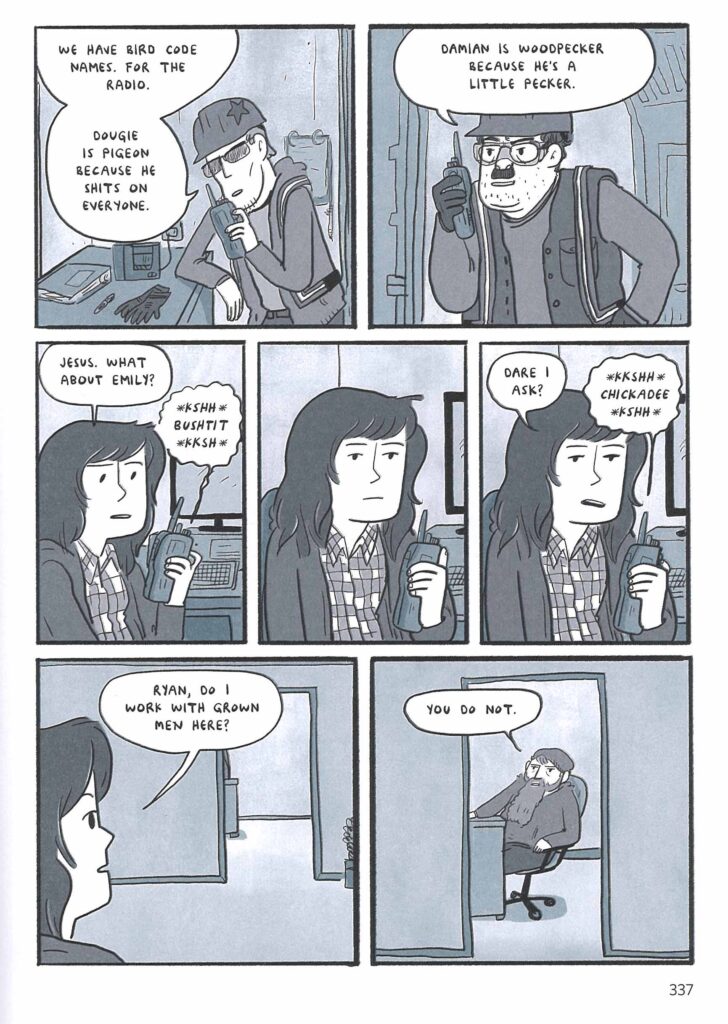

Yet Beaton also demonstrates how, among the co-workers she gets to know best, she learns to recognize the ways—albeit exhausting, and sometimes offensive—that they attempt to bring her into the fold:

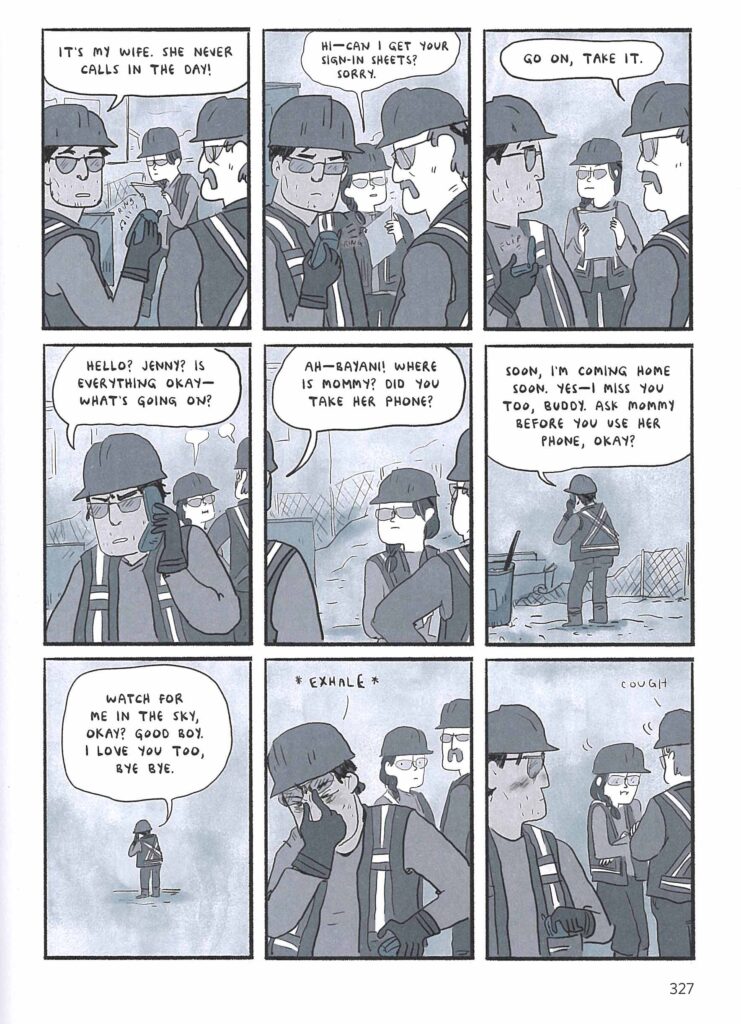

Scenes like this elicit more than one Charles Schulz-style “Good grief!” eye roll, a relatable combination of annoyance and affection. Other scenes work to combat media-driven oversimplification of her co-workers from a more heart-wrenching angle. Here, a colleague gets a phone call from home:

As Beaton told the Canadian journal “The Narwahl,” she never forgot the moment when the man “dropped his facade in front of us, in a place where you’re performing a certain kind of masculinity in the workplace. . . . [I]t broke my heart.” Still makes me tear up every time I read it, too.

I mentioned that Beaton is angry, and she is, yet she directs her anger where it belongs: toward the profit-driven social structures—and a handful of higher-ups—that bring out the worst in her co-workers. Beaton also doesn’t claim innocence herself. When asked by “Fort McMurray Today” to reflect on her time in the oil sands, she replied, “It’s complicated. I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing if I hadn’t gone out there to pay off my student loans.” As she told “Wired,” “All I could do was tell things with honesty.” Beaton suggests in her afterword that she—and especially her family—paid a high price for the choices they made at this difficult time. Nevertheless, she continues to choose radical compassion over reductive retreat.

“Ducks” puts the language of comics to its best use, presenting the oil sands’ tangle of ethics and survival and encouraging readers to think more and more deeply—on this page, for example:

Nature versus industry, right? But that reading only scratches the surface in a Kate Beaton comic. A conversation about this fox a few pages later encourages readers to flip back to this sequence and look more carefully for details they might have missed in the image. Perhaps to solve the problem of the oil sands rather than simply rail against it, readers would also benefit from more complicated thinking, revisiting what they might have missed, to create a more productive vision of how to move forward.