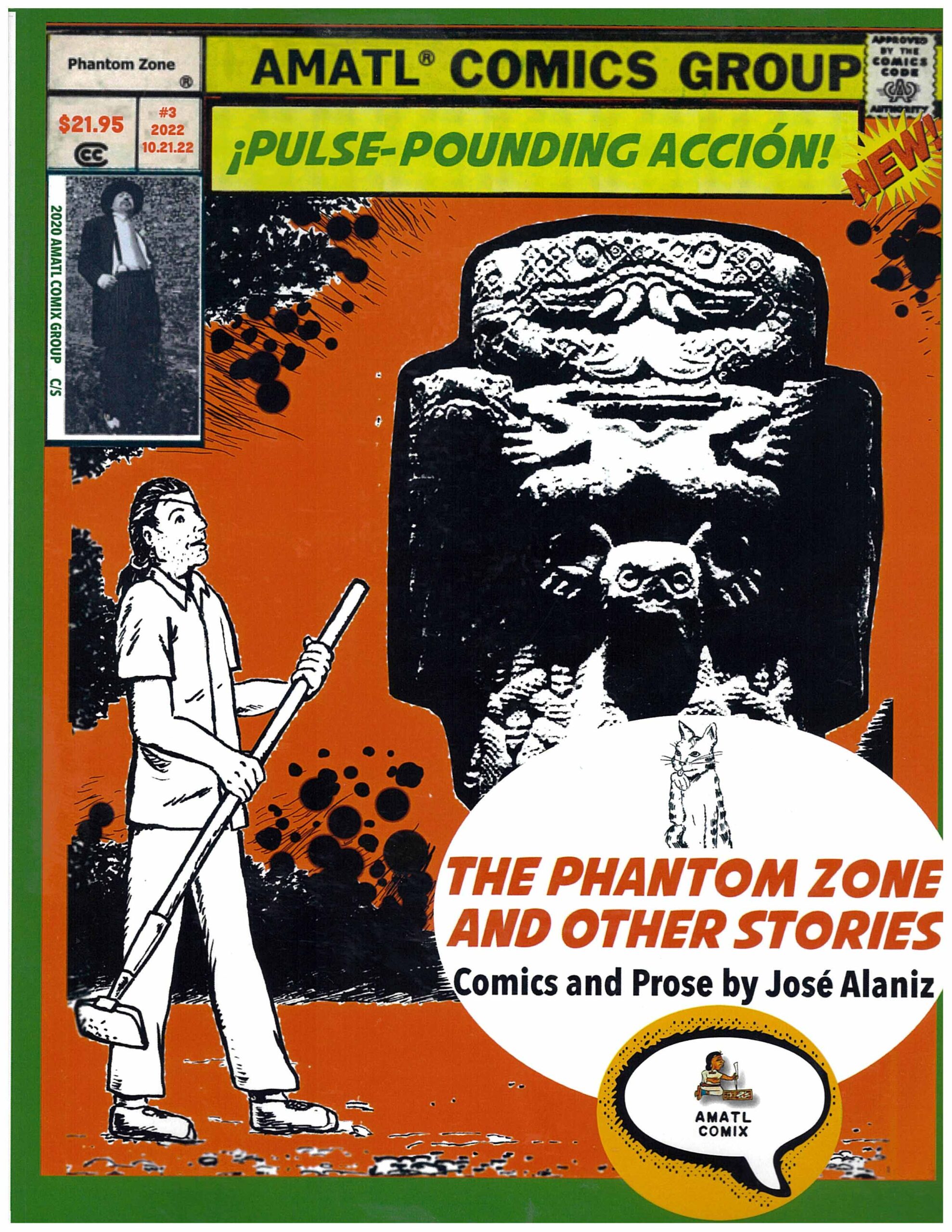

“The Phantom Zone and Other Stories.” Written and illustrated by José Alaniz. San Diego State University Press: Amatl Comix Series, $18.95 direct from SDSU, January 2020. 128 pp. Adult: drug references, some depictions of violence, some sexual content.

Thanks to Fables Books, 215 South Main Street in downtown Goshen, Indiana, for providing Commons Comics with books to review.

Check Fables out online at www.fablesbooks.com, order over the phone at 574-534-1984, or email them at fablesbooks@gmail.com.

NOTE: José and I are fellow comics academics, and he gave me a free copy of this book.

Comics “rewired my brain at a very early age,” says comics scholar and artist José Alaniz in the introduction to his retrospective comics collection, “The Phantom Zone and Other Stories.” Alaniz says that he viewed the world through comics-tinted lenses—so much so that the first time he saw the New York City skyline, he “could have sworn [he] saw caped figures flitting among the skyscrapers.”

He developed his own strip, “The Phantom Zone,” while a student at University of Texas at Austin in the early 90s. The 90s was a zeitgeist period for Austin’s campus comics: Alaniz’s strip ran alongside early work by now-superstars Chris Ware, filmmaker Robert Rodriguez, and animators Tom King and Jeanette Moreno King. The complete run of “The Phantom Zone,” which takes up about half of this book, provides a funny, dark, and fascinating alternate window back into 90s Austin. Many of us know this milieu mainly through the Richard Linklater film “Slacker,” which helped popularize Austin, and may also have helped to define Generation X (although Linklater resists that reading of the film).

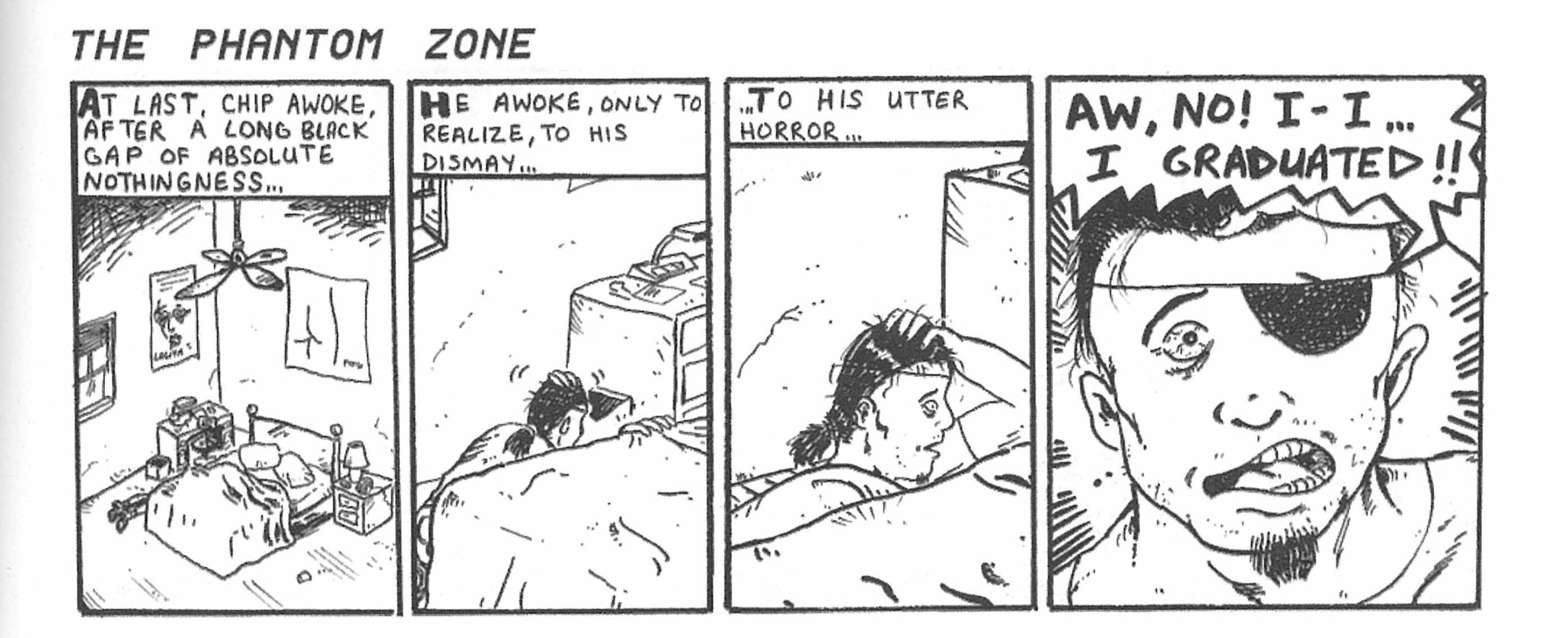

In the four-panel opening strip, Chip, Alaniz’s protagonist, passes into the “phantom zone” of post-college life. His hangover is both literal and philosophical:

Superman fans will recognize the strip’s title as the alter-dimensional jail where Kryptonian society imprisoned its villains. This holding pen, which flattened its exiles into a rotating pane of space glass, proves an apt metaphor for the existential weirdness of post-college life. Chip is in his own phantom zone after both his girlfriend and, in a sense, his college, have “broken up” with him and left him to fend for himself. This book’s 2020 release feels particularly appropriate, highlighting the time of the pandemic as a phantom zone in its own right.

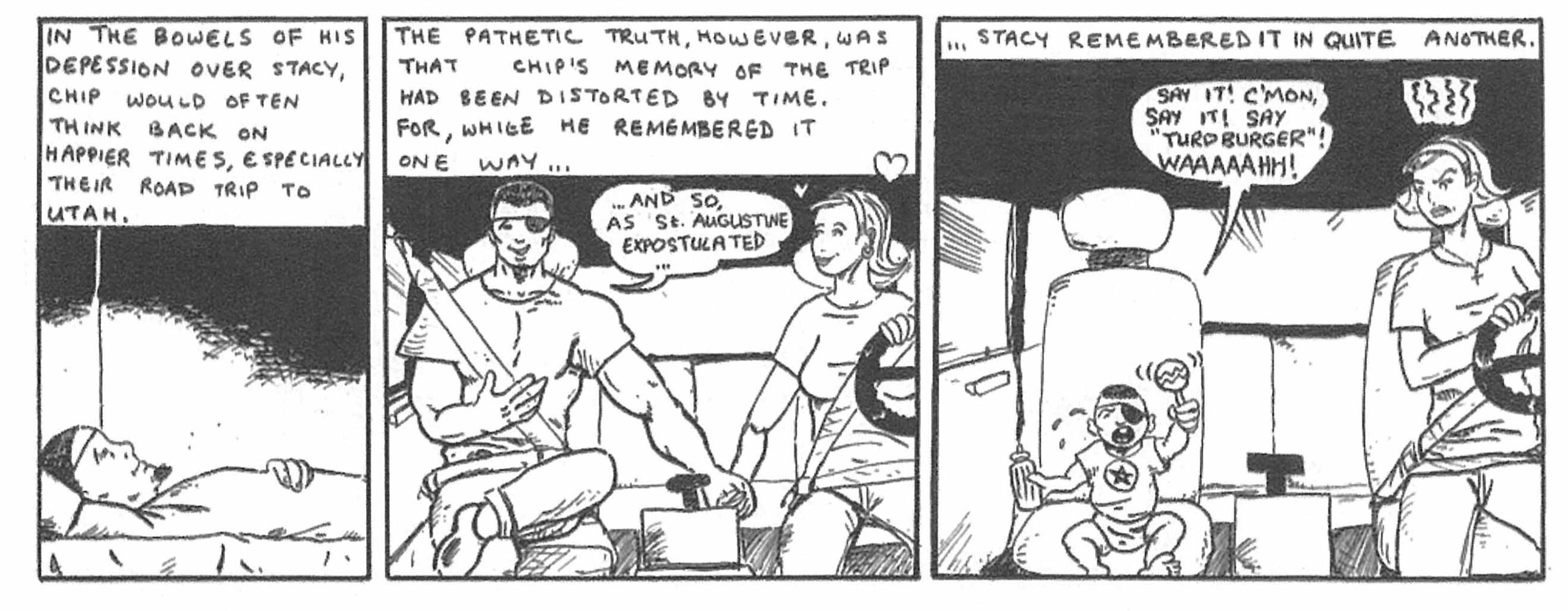

If that all sounds heavy, rest assured that the strip tempers its more intense content with expert black humor. Alaniz manages the (usually) four-panel beat with depth and dexterity; I almost spit out my coffee snort-laughing on more than one fourth-panel punchline. The best lines are often delivered by the talking cat Seymour, who serves as both sidekick and moral compass, until he becomes trapped in an animal research facility:

Much of this strip feels ahead of its time, especially in its address of issues of gender and sexuality. Witness, for example, this commentary on what we now label toxic masculinity:

Like “Peanuts,” “Calvin and Hobbes,” and many more of its distinguished comics precursors than I have room to discuss here, “The Phantom Zone” is a stealth philosophical strip—but be forewarned that its edgy, adult content is better suited for Mad Magazine than the Sunday funnies.

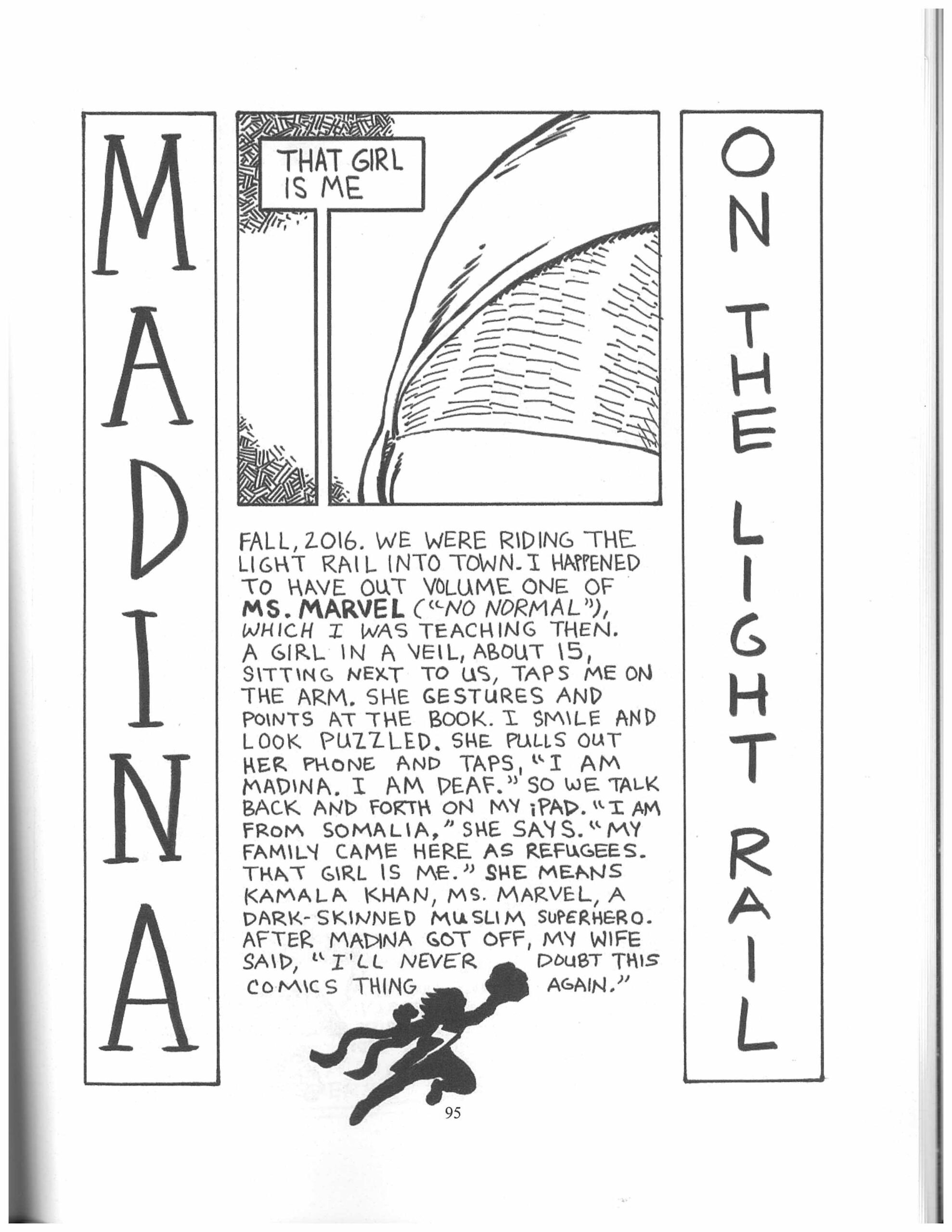

The second half of the collection heads into a mostly chronological mix of styles, and it’s both entertaining and fascinating to witness the breadth of and changes in Alaniz’s voice and visual style. As he told fellow comics artist Maxx FG on the YouTube channel Push Pull, “I think you get to see that I’m not really adhering to any one style, . . . and that’s important to me.” Part Two journeys from a superhero narrative to a fotonovela (a term from Spanish-speaking countries for comics made from photos rather than illustrations), complete with musical score. The last portion of the book settles into Alaniz’s current style: slice-of-life vignettes, often only one page, with striking framing and design:

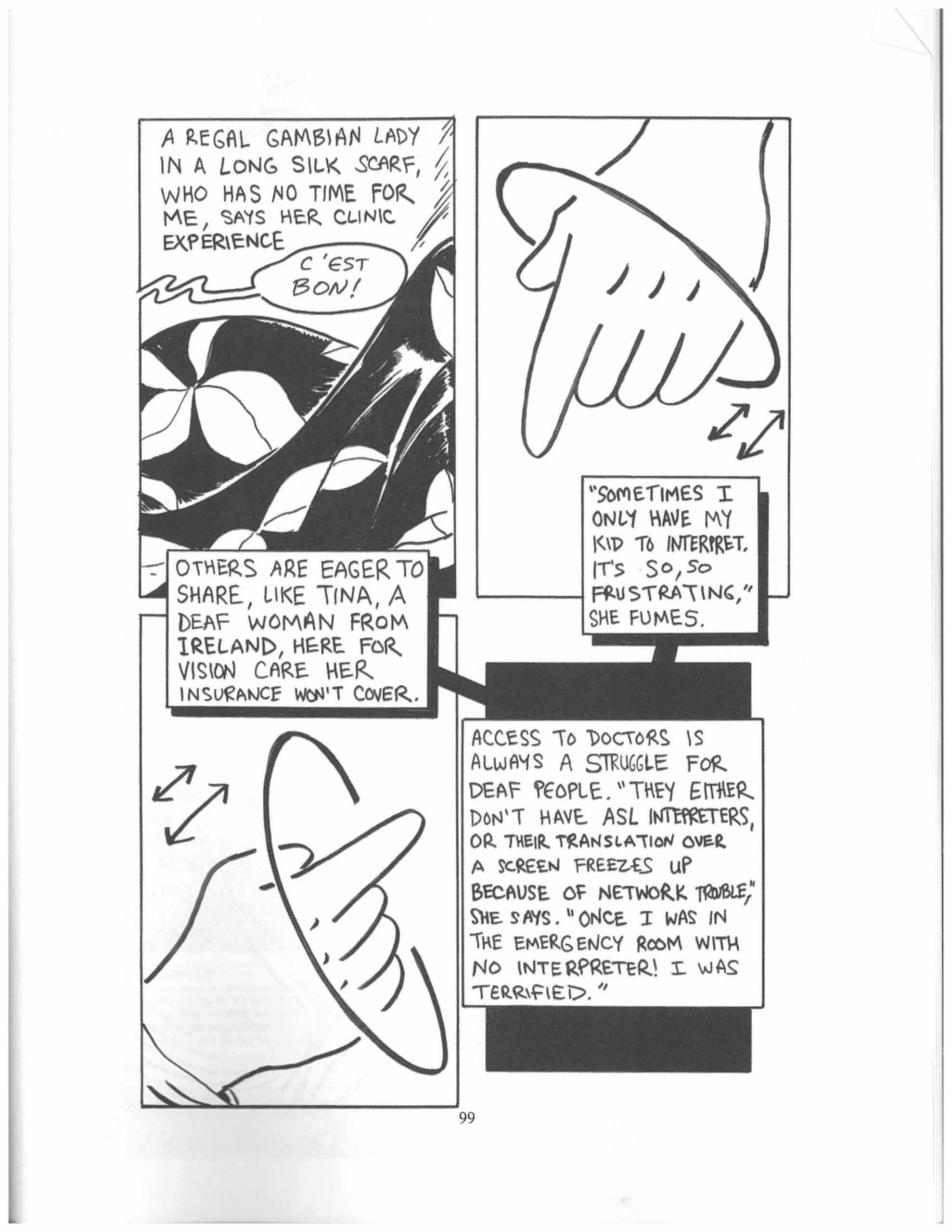

In a stylistically similar piece called “The Unseen,” Alaniz documents his volunteer work at a local health clinic, turning his artist’s lens to witness its stunning array of humans by means of setting, dialogue, movement, and articles of clothing, but no faces:

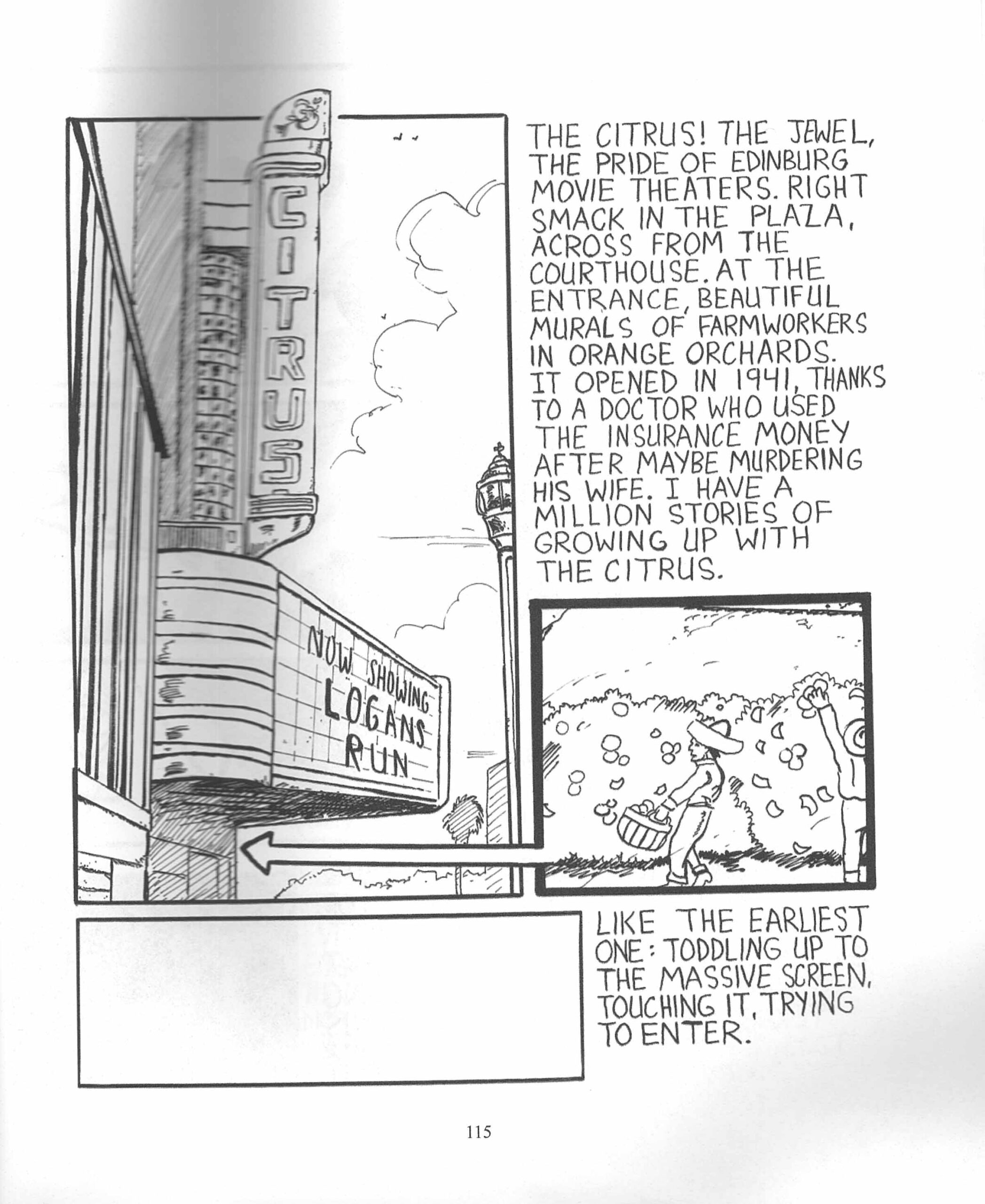

Some of the strongest pieces in the second half of the book center around the buildings that have disappeared or might soon disappear from Edinburg, Alaniz’s Texas hometown, since he lived there as a kid:

These brief vignettes are my favorites: stained-glass windows that provide illustrative architecture for the intersections between memory, nostalgia, and cultural and historical significance. Alaniz is working on a whole book of pieces like this, as he told Peter Kelley at the University of Washington, where he’s a professor of Slavics and Comparative Literature. The working title for the collection is “Fronteras de Fierro: Life on the Border in the Age of Walls,” and Alaniz is in the process of compiling “interviews, on-the-scene reporting, and my own memories of growing up in the Rio Grande Valley of South Texas, to convey a sense of how the border wall has impacted the culture and environment there, especially since the 1990s.”

“[W]onderful and wonderfully demented,” is the description novelist Gary Shteyngart applied to Alaniz’s most recent collection of strips, “The Compleat Moscow Calling,” which Alaniz wrote as a college and post-college expatriate in Moscow. Readers of “The Phantom Zone and Other Stories,” with its 30 years of eclectic work, from Austin in 1992 to Seattle of 2020, get to experience the dark humor of his more “demented” stories, as well as the compassionate economy of his more recent pieces. No matter the shape his comics take on the page from here, I look forward to seeing more of the world through Alaniz’s still comics-tinted lenses.