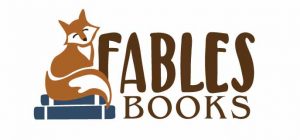

“The Keeper: Soccer, Me, and the Law That Changed Women’s Lives.” Written and illustrated by Kelcey Ervick. Avery (Penguin Random House), $27.00. October 2022. 336 pp. Teen to adult.

Thanks to Fables Books, 215 South Main Street in downtown Goshen, Indiana, for providing Commons Comics with books to review.

Check Fables out online at www.fablesbooks.com, order over the phone at 574-534-1984, or email them at fablesbooks@gmail.com.

NOTE: The publisher sent me a free review copy of this book, and Ervick and I are friends and fellow Michiana-area comics nerds.

HISTORICAL NOTE: It’s an auspicious day for a post about women’s soccer! On November 30, 1991, the US Women’s National Team beat Norway 2-1 in the first official Women’s World Cup. Hall-of-famer Michelle Akers scored both goals.

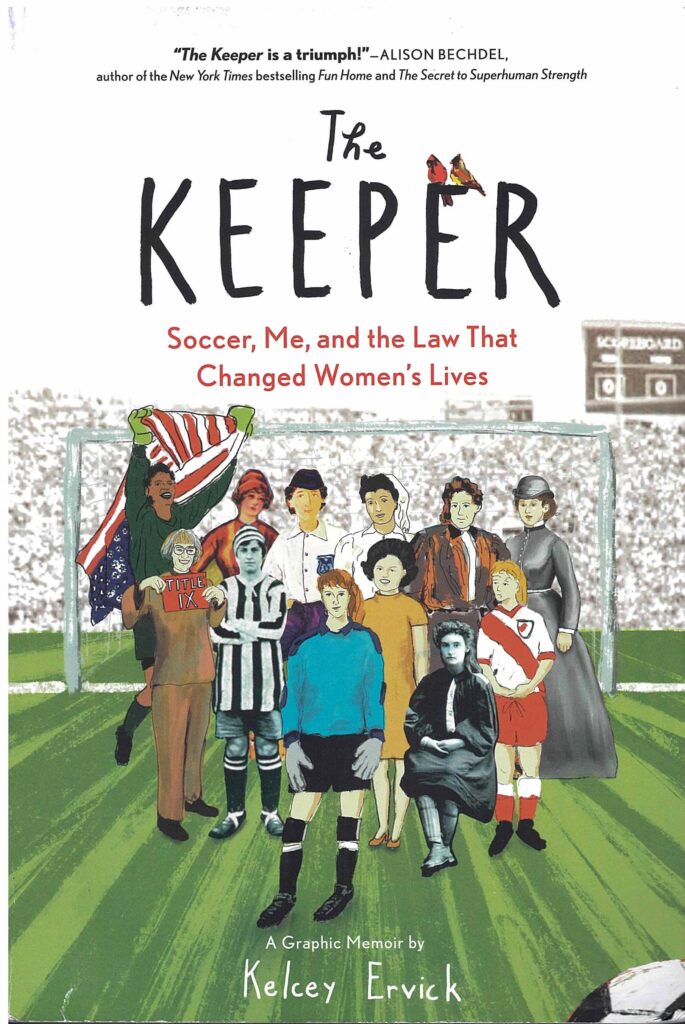

When Kelcey Ervick was growing up, she played on as many of her local sports teams as she could: football, baseball, basketball. She was often the only girl—there were no separate leagues for her to join. As Ervick relates in the image below, her father had hoped for a son, but didn’t let the designation on her birth certificate alter her training:

As Ervick makes clear on this two-page spread and throughout the book, striving for success as a female athlete was, and still is, complicated. “Draw blood!” her dad yells on the left page, while on the right, elementary school “career cards” reinforce less aggressive, as well as drastically less ambitious dreams. Outside of the arts and, inexplicably, biology, Ervick’s check-box options were restricted to traditional helping roles like secretary or nurse. The presence of “mother” on the girls’ side without an equivalent “father” on the boys’ side likewise speaks volumes.

The release of Ervick’s book coincides with the fiftieth anniversary of Title IX, the law that paved the way for women’s equal access to education, and that played out most visibly in athletics. You don’t have to love sports to love this book, however. As Ervick recounts in a recent “Washington Post” article, Title IX itself had little to do with sports when it was enacted in 1973. The core group of women who fought for Title IX had been barred from careers in law, medicine, politics, and engineering, as well as academia, where Ervick, a college professor at Indiana University South Bend, has made her professional home.

“I thought that the reason I was involved in all these sports growing up was because my dad was an athlete,” Ervick explained in an IU news article. “I didn’t realize there had been a whole movement, and the only reason there was a team at my high school or college was because of Title IX.”

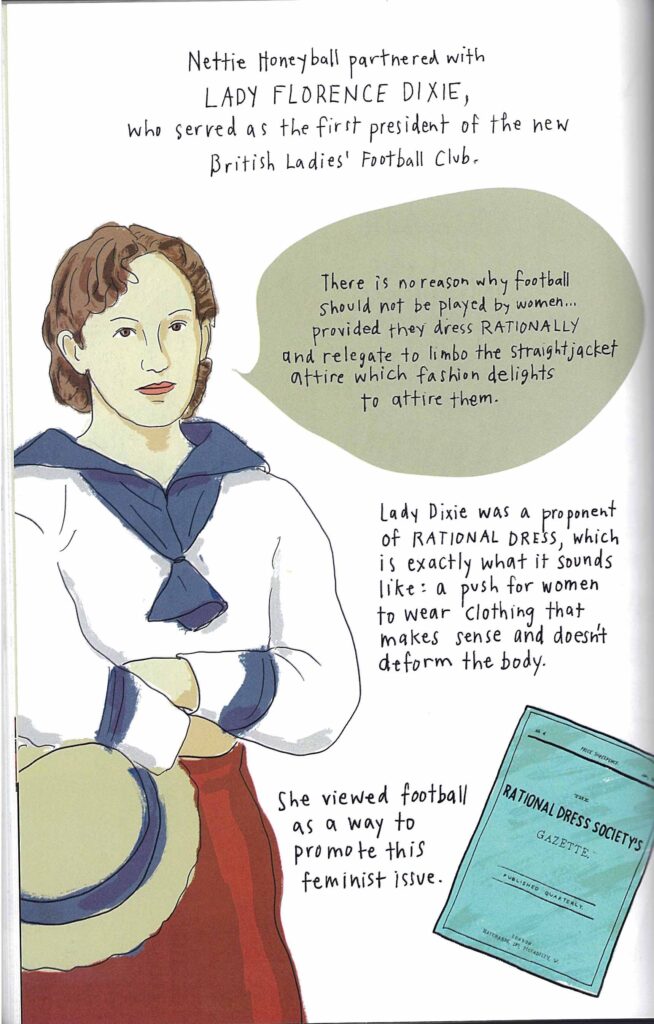

Some of the book’s most fascinating sections dive into the history of organized women’s soccer. The Scottish woman who started a series of “Ladies’ Football” exhibition matches in 1881 in England had to advertise under a pseudonym (“Mrs. Graham”) to protect herself from threats and abuse. Fourteen years later, “Nettie Honeyball”—clearly another pseudonym—stared the first women’s league. As the press began its torrent of, as Ervick puts it, “mockery, condescension, and obsession with [the players’] bodies,” Honeyball focused on marketing, recruiting a feminist writer to serve as president of the league:

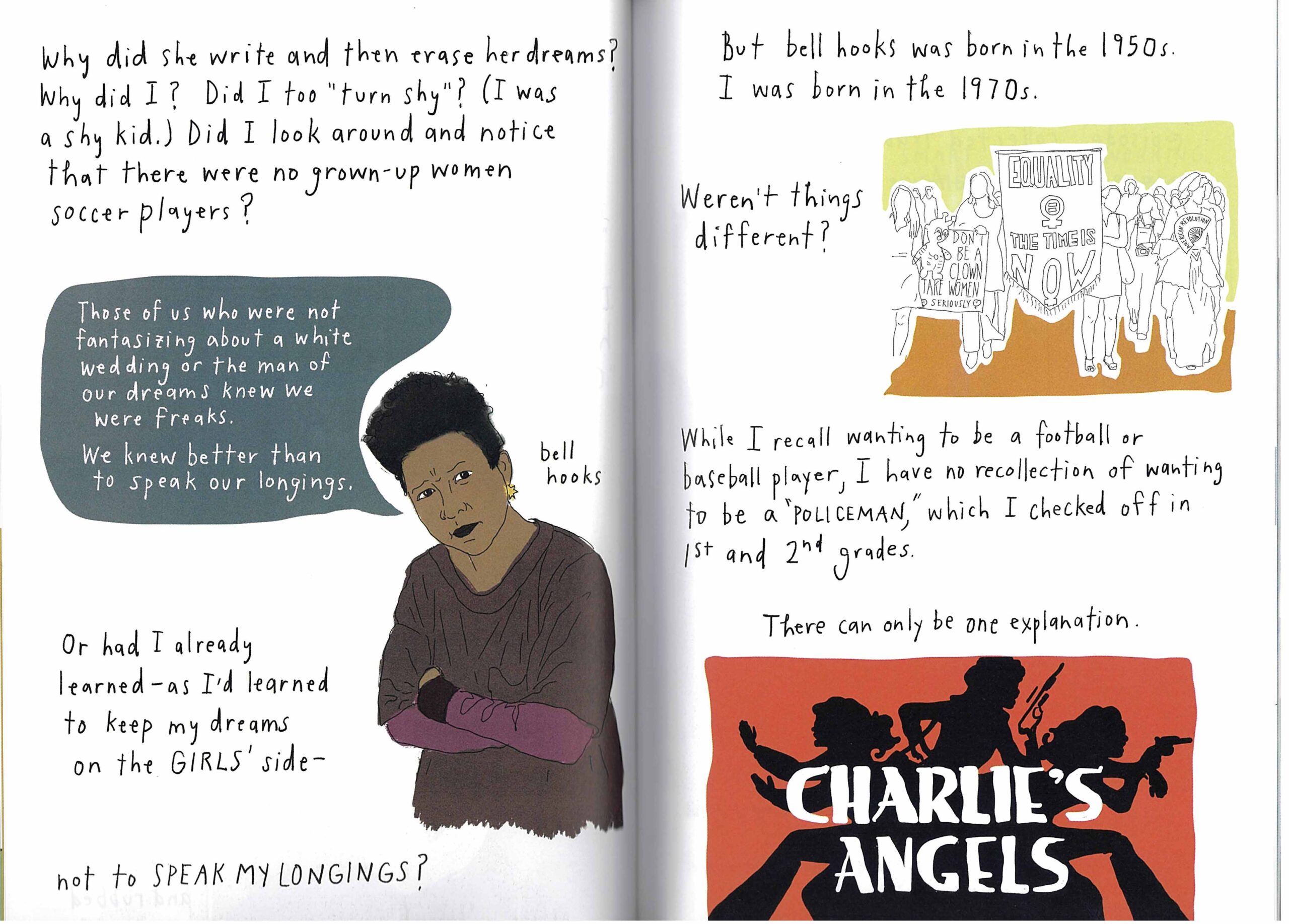

The struggles of these early British women’s teams—including the best known of them, the Dick, Kerr Ladies—weave into and around tales of Ervick’s own struggles to navigate a supposedly “liberated” Western society not only as a female athlete, but also as a writer, and eventually a mother. Ervick puts her English professor training to work by interspersing the voices of Nabokov (a fellow goalkeeper), Oscar Wilde, Virginia Woolf, bell hooks, and other literary luminaries. One especially striking two-page spread extends out of a passage by Woolf, who recalls seeing her sister, the artist Vanessa Bell, write and then furiously erase the phrase “When I am a famous painter.”

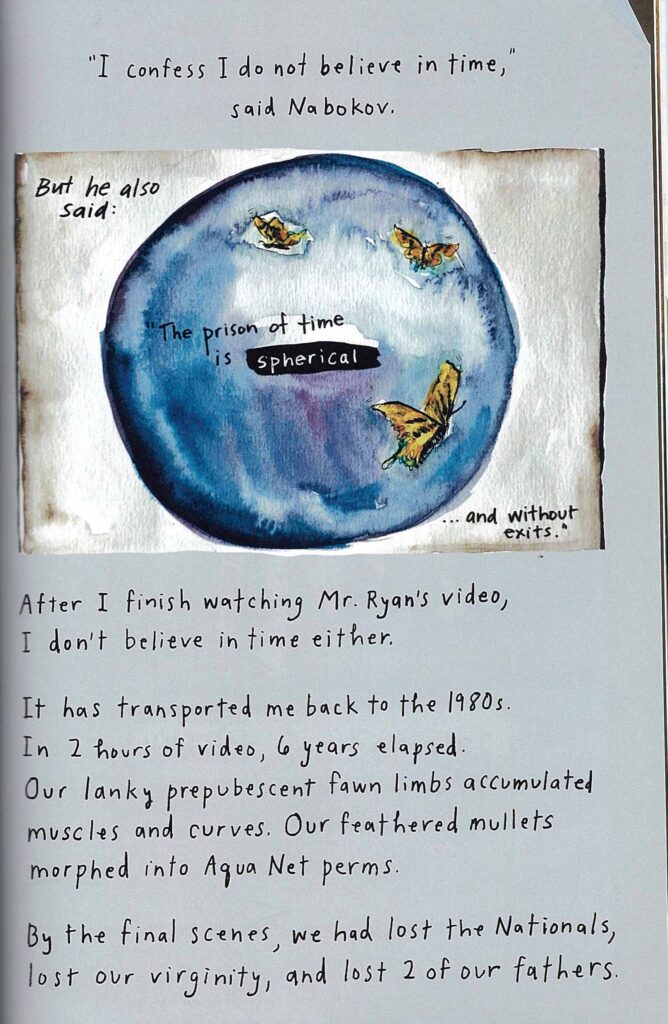

The effortless transit from Woolf to hooks to Charlie’s Angels is typical within this book. The narrative’s fakes and feints are carried out as seamlessly and expertly as Megan Rapinoe threads through her opposing team’s defense to score a goal. Every time I began turning the pages too fast, carried away with the story, Ervick would slow me down, reminding me to savor the writing, the art, and especially the electricity created by the two in combination:

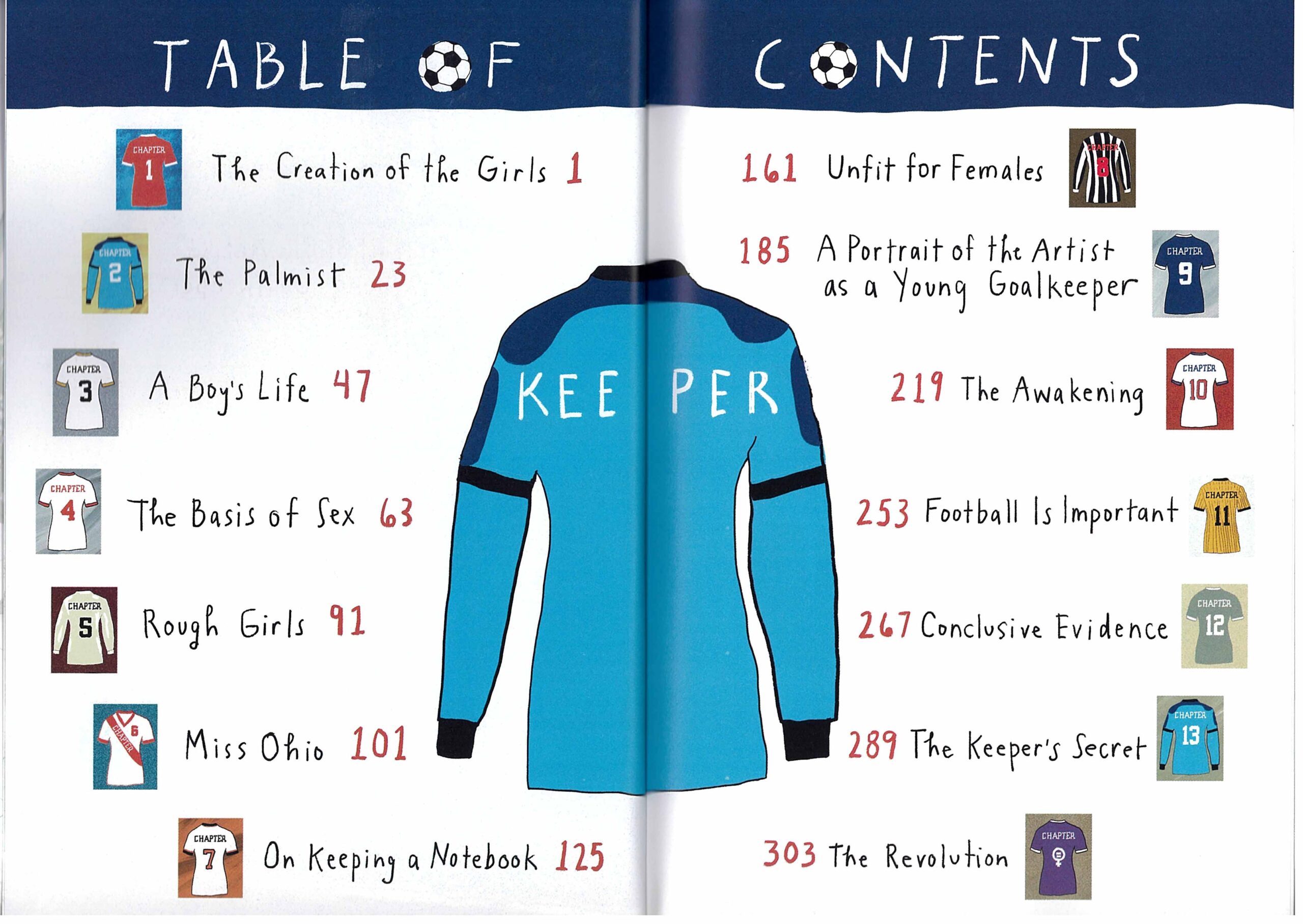

You can watch the video referenced above, made by travel team dad Mr. Ryan, on the homepage of Ervick’s website. Ervick’s prose conveys the unnerving yet oddly warm and enveloping experience of watching an earlier self—both so foreign and so familiar—in old home footage. Yet she doesn’t dwell on the insular trap of nostalgia, instead looping in and out of past and present, as her table of contents quite literally illustrates:

Ervick revisits those “career cards” throughout the story, discussing how she toggled back and forth between writing “soccer” and “athlete” on the blank line—sometimes, like Vanessa Bell, writing them in only to cross them out. By the time Ervick reached sixth grade, however, she had abandoned the fill-in-the-blank option. She stopped checking the “mother” and “biologist” boxes, restricting her imagined future to “model.”

I remain grateful that Ervick ultimately chose not to follow the sixth-grade version of her future down the fashion runway, and I believe you will be grateful too, whether you’re a fan of soccer, literature, human rights, a good read, or all of the above.