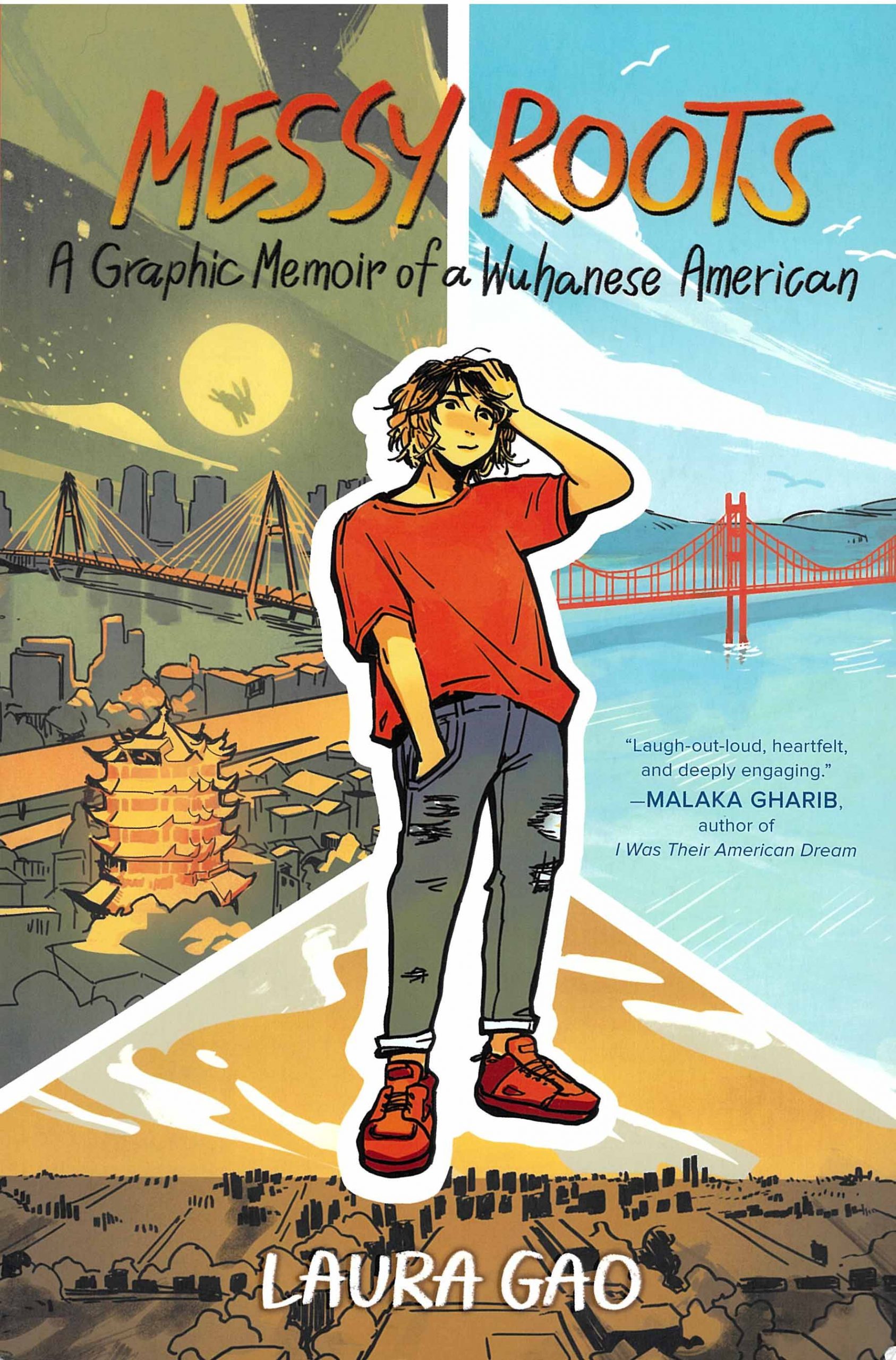

“Messy Roots: A Graphic Memoir of a Wuhanese American.” Written and illustrated by Laura Gao. Color and additional illustration by Weiwei Xu. HarperCollins/Balzer + Bray, $22.99. March 2022. 272 pp. Teen and up.

Thanks to Fables Books, 215 South Main Street in downtown Goshen, Indiana, for providing Commons Comics with books to review.

Check Fables out online at www.fablesbooks.com, order over the phone at 574-534-1984, or email them at fablesbooks@gmail.com.

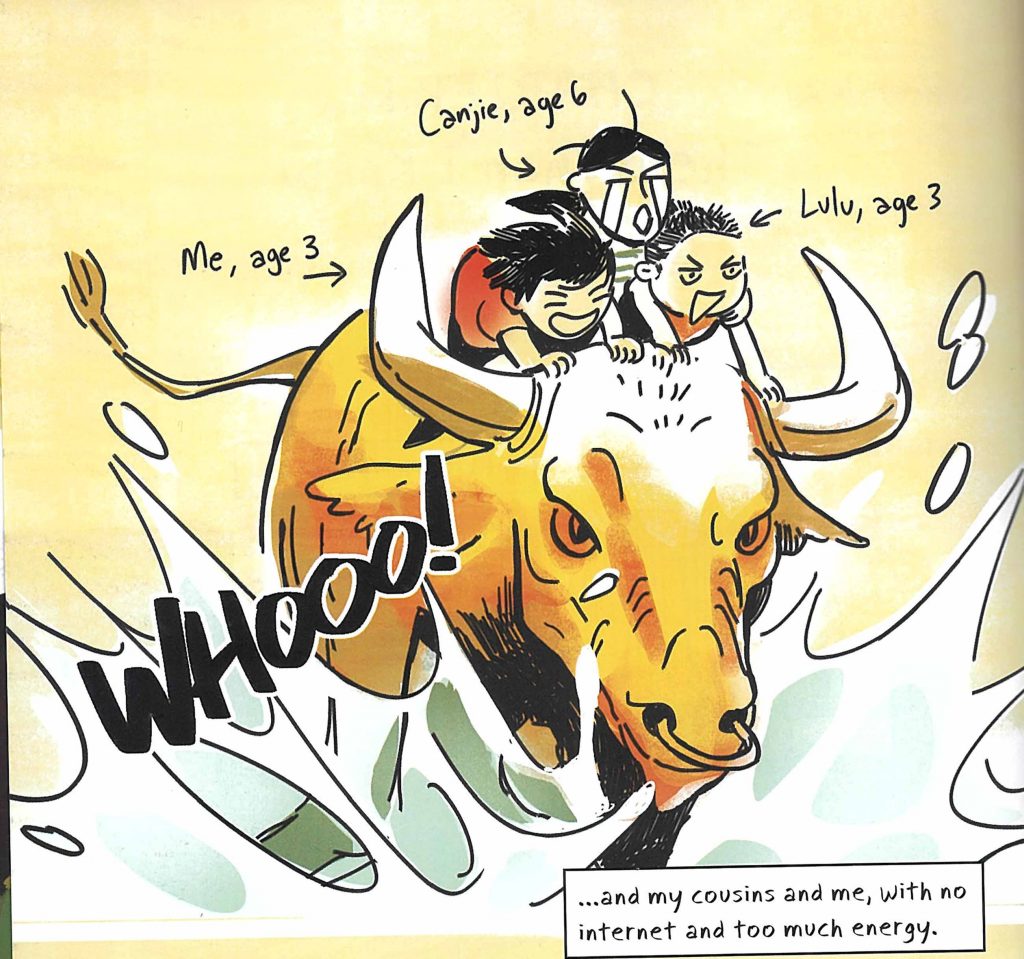

In her graphic memoir “Messy Roots,” Laura Gao begins with her earliest years in Wuhan, China. She was raised by her grandparents while her parents started graduate school in the US. Gao was quite young, but still holds fond memories of playing with her cousins:

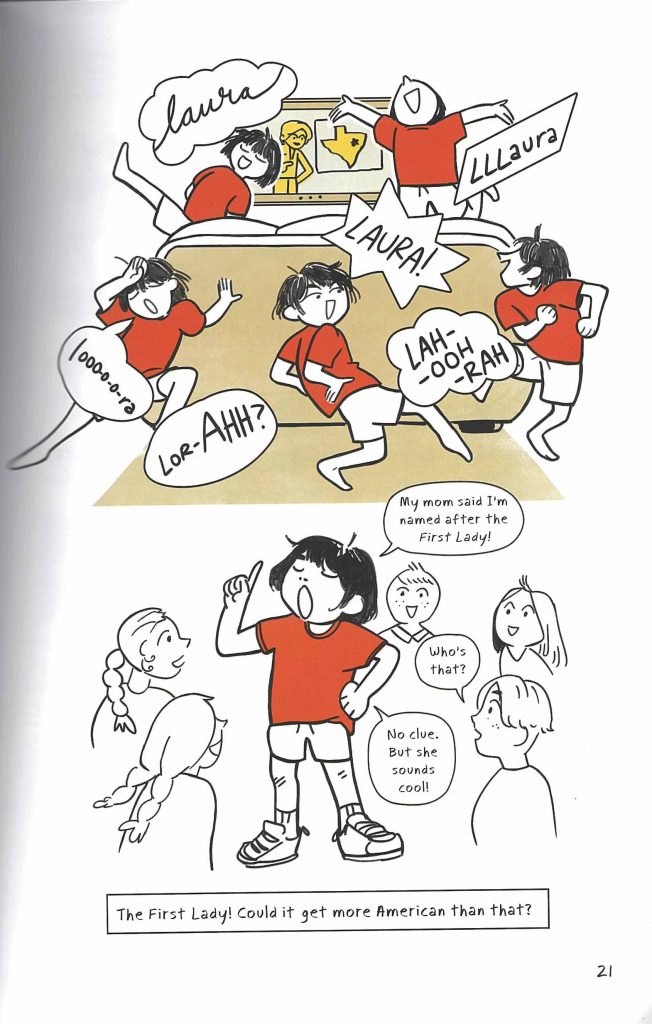

Gao’s parents returned to China to fetch her when she was four, and brought her back to the US with them, to the small Texas town of Coppell. It was a shock: she didn’t at first know her parents any better than she knew English or the US. As a survival strategy, she pushed the Wuhan elements of her identity into the background. Since school roll call was “a living nightmare” for pre-K Gao, she asked her parents if she could change her name from Yuyang to something more American-sounding. Her mom suggested Laura, after Laura Bush, first lady at the time.

Gao felt that her name change had made her school life so much better that she convinced her parents to let her name her newborn brother: hence Jerry, after the slapstick cat-and-mouse cartoon Tom and Jerry, “the first official American of the family.”

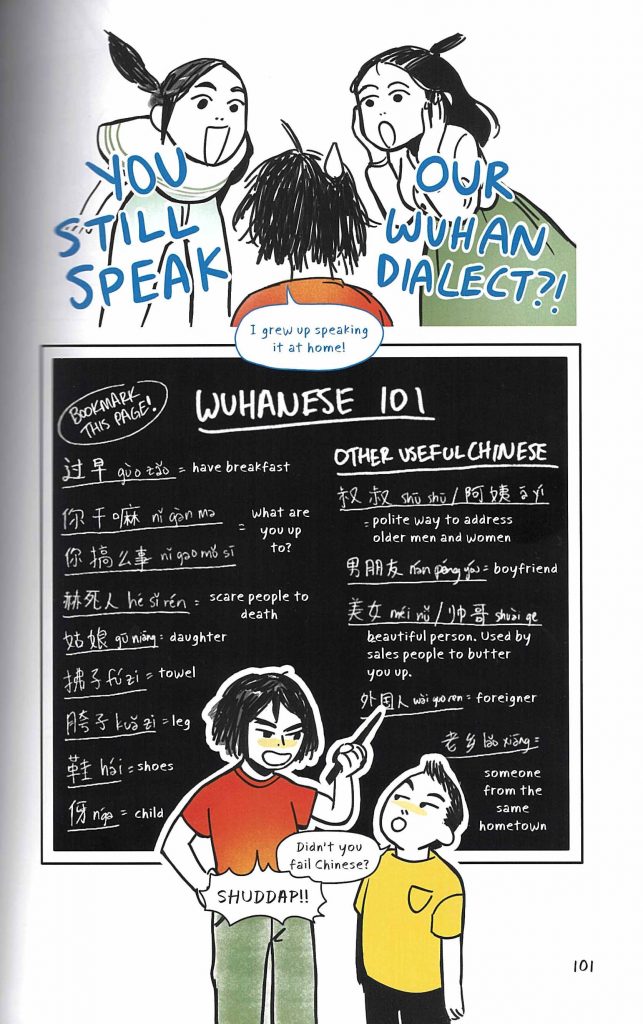

Gao didn’t return to Wuhan until she was a teenager. Her parents had made her go to Chinese school on the weekends for years, but she had resisted it so much, she was almost as surprised as her relatives were that she could still speak with her cousins:

Gao was planning to visit Wuhan again in early 2020, but the pandemic canceled her trip. By that time, she was a recent college graduate working at Twitter, illustrating on the side, and fed up with the US media’s clumsy and often racist representation of her ancestral hometown. In answer to the in-person and online abuse she encountered on a daily basis, she created and posted a comic called “The Wuhan I Know.” Her timing was perfect: the comic went viral, answering questions about the pandemic’s ground zero, a city that many in the US were hearing about for the first time. Gao leveraged the comic’s meteoric rise into a book deal for “Messy Roots,” this full-fledged memoir.

Gao cites a letter from an Asian mother as a crucial moment in the development of the book. The mom said that her daughter loved and related to “The Wuhan I Know” so much, she was frustrated that she had been unable to find anything else like it. She asked Gao for more work. Gao was both touched and anxious. As she explained to “Input Magazine,” “I was 23, and I was still playing identity tug-of-war with my therapist. . . . I was like, ‘Man, I can’t even use chopsticks correctly. I don’t know if you want me as the expert on this.’” But Gao also realized how much she would have appreciated reading a story like hers when she was younger. She fortified her workspace with sticky note reminders of her newfound purpose: “You are writing this for younger Laura and other younger Lauras out there.”

Gao’s story of her struggles to reconcile her Wuhan roots and her US youth is already rich and complex material for a substantive y.a. memoir. But as she worked to expand her short comic into a full book, she knew that she wouldn’t be telling the whole story if she didn’t weave her queer coming of age into the threads of the narrative as well. Gao’s openness and honesty are key to this book’s success: she doesn’t try to hide her experiences with racism, sexism, and homophobia. One of the funniest and most touching pages is when she comes out to her brother Jerry:

Neither is Gao shy about the moments when she herself makes mistakes. Her willingness to share stories she’s not proud of is not only disarming, but a gift to her young readers. On the below page, she shares an embarrassing moment that helped her come to terms with her own internalized stereotypes. New to college—the University of Pennsylvania—and visiting her first Chinese Student Association event, a new acquaintance welcomes Gao into a conversation, saying, “We were chatting about the number of Asians at Penn. There’s too—”

Gao may be young, but pages like this showcase not only maturity—how many of us share the worst things we’ve said with a bestseller-level audience?—but expertise in paneling, pacing, and simple but powerful facial and bodily expression. On the page above, for example, witness how easy it is to grasp the contrast between Laura’s nonchalance and the shock of the rest of the group, yet how few lines and details convey this explosive moment.

Much like the style of Malaka Gharib, an early proponent of Gao’s work, “Messy Roots” values exuberance over precision. Her advice about building an artistic practice is useful for artists of any age and in any format: “Always start small and post that work, no matter how crappy it looks! The quicker you get over your perfectionism, the faster you’ll finish projects, get feedback, improve, and overcome imposter syndrome or ‘artist stage fright.’ . . . Ultimately my goal is to tell a story; I don’t need to be perfect to be impactful.”

Similarly, Gao’s most common refrain in her interviews when discussing her own messy process of growing up is “and that’s okay!” When “The Honey Pop” asked what advice she had for queer young readers “still trying to find themselves,” she suggested, “Think of it less as a “coming out” and more of a “coming into” yourself”—useful advice that the book as a whole embodies.

Gao puts a lot of weight on the extended metaphor of her book’s title, as well as her other metaphors such as “genes” and “jeans.” Such wordplay works hard to reinforce exactly what her youth audience—and the younger Laura of her sticky notes—needs to hear: find yourself, be yourself, and you don’t have to have all the answers yet. Frankly, she seems to add, you might not ever have all the answers. And that’s okay.