“It’s a marketing term. . . . The problem is that ‘graphic novel’ just came to mean ‘expensive comic book.’ Because ‘graphic novels’ were getting some attention, [publishers would] stick six issues of whatever worthless piece of crap they happened to be publishing lately under a glossy cover and call it The She-Hulk Graphic Novel, you know?”

–Alan Moore, creator of Watchmen and other acclaimed long-form comics, in a 2000 interview on blather.net

A lot of people ask me what the difference is between a comic and a graphic novel. In simple terms, a graphic novel is a comic with more “literary” goals than most serial comics. In the same interview cited above, Moore also lists “density, structure, size, scale, [and] seriousness of theme” as some of the qualities that might lead someone to classify a comic as a graphic novel instead.

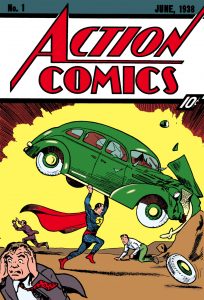

As you can tell from the tone of Moore’s quote, though, many artists and writers in the field hate the term, especially because of the snobbery they think it implies. (Although Moore is being pretty snobbish himself: She-Hulk is a fascinating character.) Many people highly invested in the term “graphic novel” have had a tendency to dismiss superhero comics as less worthwhile—a pet peeve of mine, not only because I love it all, but also because the current zeitgeist of “graphic novels” owes a debt to the men and women in tights that paved its way. The superhero comics from the Golden Age of the genre taught so many people to read comics, that the more highbrow titles wouldn’t be around without Superman holding them up, like he held the car over his head on the cover of his 1938 debut in Action Comics #1.

I don’t love the term either, but my problems with it are rooted as much in its imprecision as its perceived snobbery. “Graphic narrative” is much more specific: many graphic novels aren’t novels at all—at least in the current sense of the term—but memoirs, short stories, even poems, all of which experiment with the productive tension between word and image. Yet a word like “narrative” can add to the impression that the genre has its nose in the air, too highfalutin to bother with the mainstream.

Nevertheless, the term graphic novel can be useful to mark a quick distinction between mass market titles and smaller works with very different goals, whether literary, experimental, or otherwise niche.

I give my students a much longer, more detailed lecture on the history of the term, and I’m happy to fill in those details for you all if there’s a demand. But the real point is that it doesn’t serve much of anyone, except marketers, to make a big deal out of these distinctions. As we all do with more traditional books, decide what you like, read it, and enjoy!

And learn what you can, as well. As a parting word, here’s one of my favorite artists and writers, Gene Luen Yang—just appointed in 2016 as U.S. National Ambassador of Young People’s Literature—arguing for comics in the classroom. Check out my review of Yang’s “Boxers and Saints,” and keep an eye out for my review of the just-released fourth installment of “Secret Coders,” a series that my kids and I have been reading for fun, but which has also been teaching us stealth binary code and computer programming.

You can find Yang’s works, and all of the works I review in this blog, at the ever-awesome Better World Books in Goshen:

Stay tuned for a new review in two weeks!