Originally published on GoshenCommons.org January 20, 2014

On this Martin Luther King Jr. Day, I encourage you to read, whether again or for the first time, “March,” written by the Congressman and civil rights leader John Lewis and Andrew Aydin, and illustrated by Nate Powell. See the November archives for a review.

Within “March,” Lewis mentions a 1957 comic that inspired him and college students across the country to organize the lunch-counter sit-ins that gave the civil rights movement critical momentum.

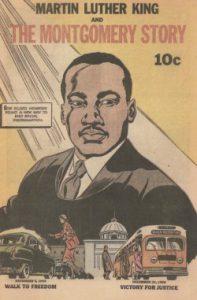

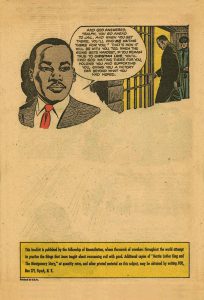

“Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story” was released and distributed by the Fellowship of Reconciliation, or the FOR. This international organization for peace and nonviolence was formed during World War One and sponsored the first U.S. freedom ride in the 1940s, which led to a close relationship with Martin Luther King Jr. in the 1950s.

You can read the whole comic online (see link at the end of this post), but very few print copies exist because it was potentially dangerous to carry it, especially in the South. Readers were told to memorize and destroy it. (If you’re local to Goshen, you can see a copy at the Mennonite Historical Library.)

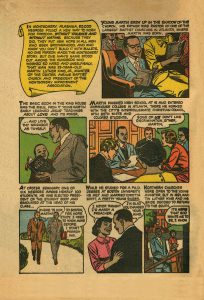

In a recent interview, Lewis referenced not only the role of this particular comic in his life, but also the power of comics more generally to educate young African-Americans and other civil rights sympathizers, many of whom had been denied access to a solid education. Asked last August on “The Colbert Report” whether comics were “dignified” enough to represent such an important history, Lewis credited this comic with making him more aware of the injustice in the South, and inspiring him to head to school in Tennessee, educate himself and begin to take action. Here are the first two pages:

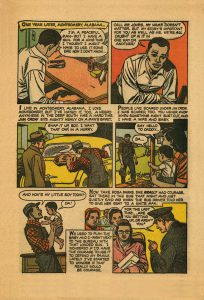

This classic comic style—matte pages, limited colors, and narration that generally stays within the frames—is refreshing to read in a comics age with a lot fewer rules, which can be exciting, but too often exhausting, confusing or both. Also striking in these first two pages of the comic is the mere presence of African-American protagonists—rare at the time—and the simplicity of their stories as they meet the standard milestones of the American dream: education, marriage and having children.

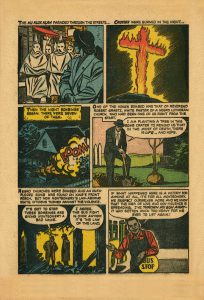

As the story moves into the violence that arose after the Montgomery bus strike, even the “Boom!” comes across as refreshingly traditional—these days writers feel as if they need to come up with a “skreeeeet” or “blammo” or something more creative but often distracting.

There are no authors or artists credited on the comic itself, but sites selling the comic now list the authors as Alfred Hassler, head of publications at the time for the FOR, and Benton Resnik, an artist and writer known mostly for horror comics like this:

According to a documentary video interview with Hassler’s daughter, like a lot of other artists in the McCarthy era, Resnik had been blacklisted for his political views, and was happy for the work. Resnik wrote the text, and Hassler persuaded a comics studio to do the drawings for free.

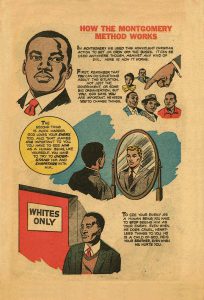

The comic’s classic style breaks down in fascinating ways in the end section, however, as the work turns instructional rather than narrative. “How the Montgomery Method Works” shifts to a white background and four main frameless images per page.

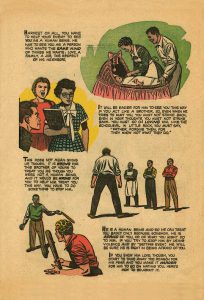

This section, the very one that instructed Congressman Lewis and his fellow student protesters, illustrates the power of comics. You can see echoes of historic images like the famous picture of Elizabeth Eckford, one of the nine African-American students who integrated Little Rock High School just a few months before the comic was released. The artists also work to help readers see themselves in these figures, however—the white space that surrounds them allows the reader in, and the focus is on the individual.

Perhaps the most powerful page, which walks the reader through the “steps” to successful nonviolent protest, has a more detailed and disturbing parallel in “March”:

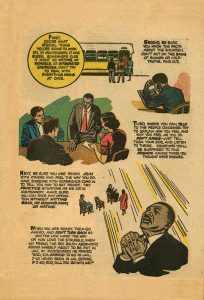

In both “March” and the 1957 comic, however, we get to see a young Martin Luther King Jr.:

The way that these images in both of the comics humanize a man who has become larger than life helps readers then and now realize the power of the individual, not as a cliché phrase, but as a real means of making the world a better and more peaceful place. Thanks to the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute, you can read the whole comic for yourself online: http://mlk-kpp01.stanford.edu/index.php/encyclopedia/documentsentry/ the_montgomery_story_comic_book/.

Next up for review—for real this time!—another historical comic with an entirely different approach: “Woman Rebel: The Margaret Sanger Story,” by Peter Bagge.

Thanks as always to Better World Books in Goshen, Indiana, and see you in another two weeks.