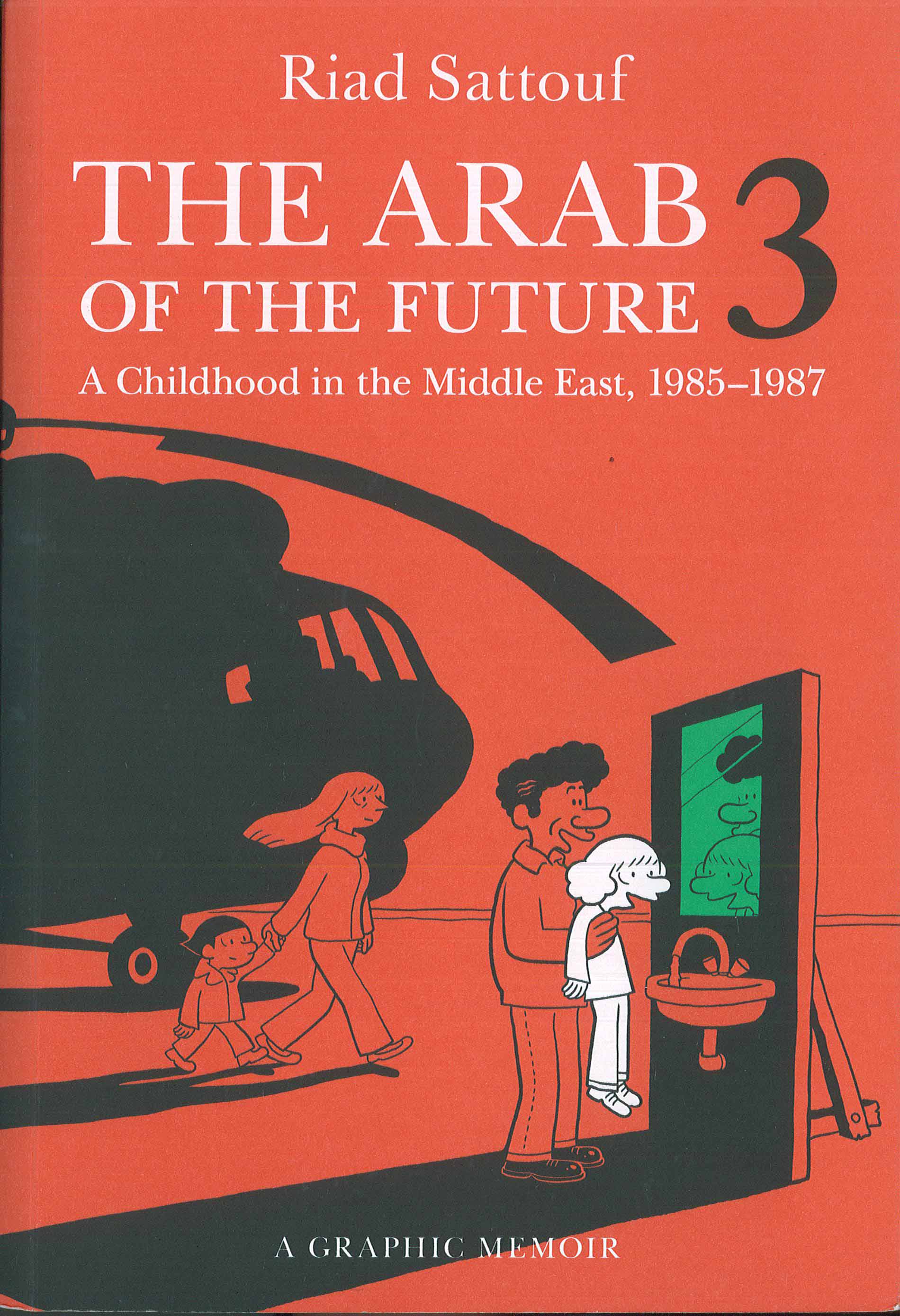

“The Arab of the Future 3: A Childhood in the Middle East, 1985-1987,” by Riad Sattouf. Metropolitan Books. Aug. 2018. Translated from French by Sam Taylor. 160 pp. Paper, $27. Adult.

Thanks to Better World Books, 215 S. Main St. in Goshen, for providing me with books to review. You can find or order all of the books I review at the store.

Many readers who love humor have a tendency to condescend to it, to see it as superficial. Franco-Syrian comics artist Riad Sattouf, however, dismisses this stereotype. “It’s very easy to make a drama. I prefer to make something funny out of a drama,” he told The Guardian in 2016, after the release of the first volume of his five-part series, “The Arab of the Future.” “I think sad things are easier to accept and are even sadder when they’re told with humour.”

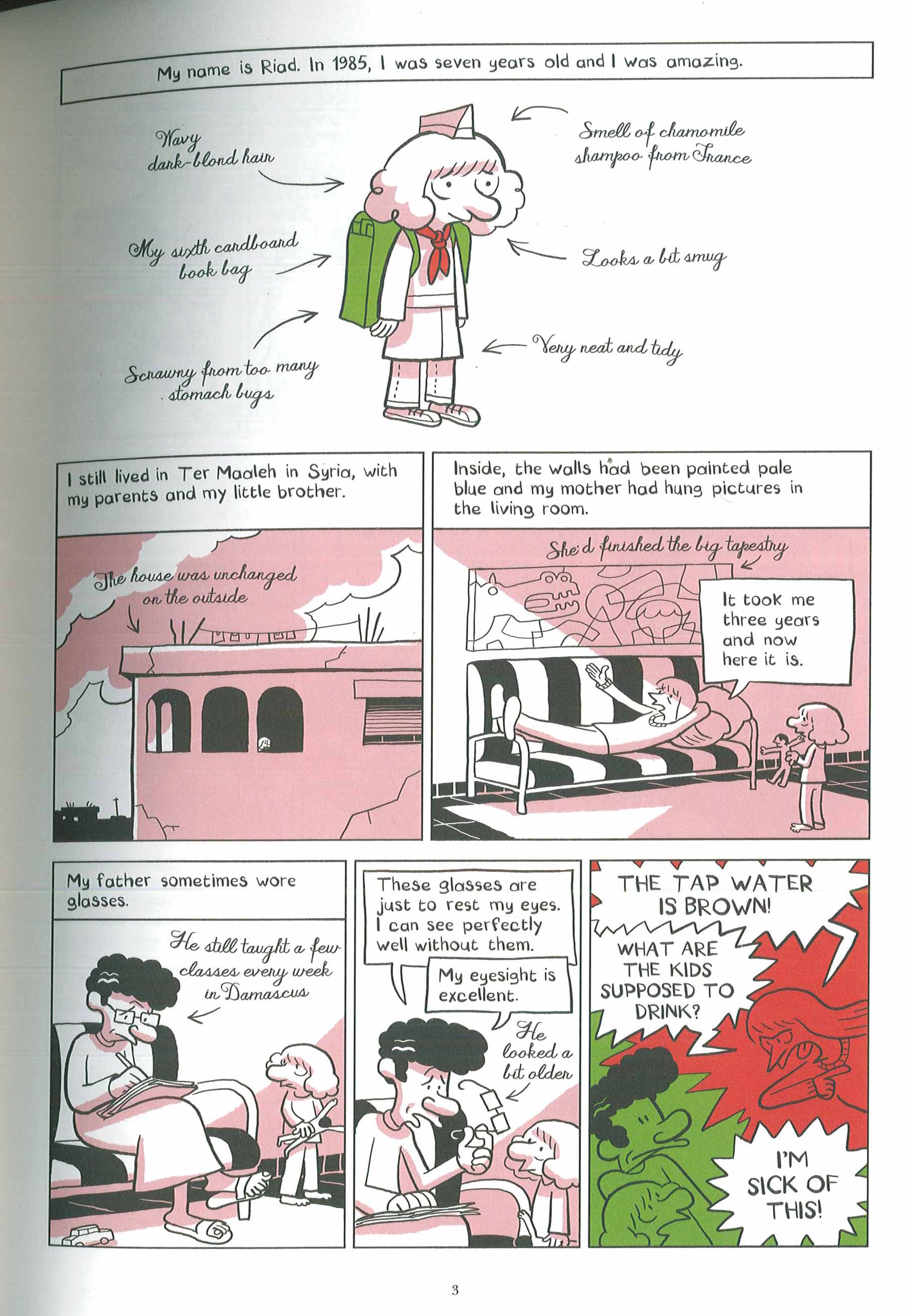

A rich and wrenching graphic memoir of Sattouf’s childhood, “The Arab of the Future” is set in Libya, small-town Syria, and France in the 70s and 80s. Sattouf packs complex emotional and historical resonance into a handful of colors and a simple-looking style. Volume three, released in the U.S. last August, hits readers full force on its first page with equal parts humor and tension:

First, no worries about jumping into the series in the third volume: Sattouf deftly fills in necessary background about his “amazing” childhood self without bogging the story down.

Also more than clear on this first page is that despite the helicopter on the cover, the main battle that young Riad and his readers will witness in this book is between his parents. His mom, Clementine, is desperate to move back to France, while his dad, Abdel-Razak, holds onto a university teaching job that he’s been unable or unwilling to translate into a position outside of the Middle East. Sattouf’s father is so dedicated to a “Pan-Arabist” vision of a unified Arab society in North Africa and the Middle East that he turned down a teaching position at Oxford for a post in Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya, the main setting for the first volume of the series.

For the observant reader, however, the page contains even smaller points of tension, as suggested by the arrows and asides that tend to contradict the dialogue. Even though narrator Riad notes that “the walls had been painted pale blue,” the frame is pale pink. There’s no blue to be found on the page, only green and red clashing innocently on young Riad’s school uniform, and angrily in the frame on the bottom right. Flip through the book as a whole, and red is used almost entirely in flashes of fear, anger, and violence, with the exception of classroom kerchiefs, berries, an Etch-a-Sketch, and a brief Santa Claus cameo.

Sattouf’s measured use of bold red and green is visually powerful enough in itself, but there’s a logic behind his color choices, as he told the “L.A. Review of Books.” “For each country I allowed myself to use the colors of the country’s flag, because this is a comic about nationalism. In Syria I use pink, red, and green. In France I use red, white, and blue. In Libya I only use green.”

Much like in Marjane Satrapi’s “Persepolis,” which used the innocent perspective of young Marjane to teach Western readers about life in revolutionary Iran, Sattouf’s readers learn about these often stereotyped and oversimplified parts of the Middle East through young Riad’s observant, yet non-judgmental eyes.

Sattouf has taken flak for this approach. Volume one, a bestseller in France in 2015, triggered a wave of backlash because his critics believed its success was fueled by France’s racism and xenophobia—which may very well be true.

Yet as his supporters have noted, Sattouf works hard to spread his critique as equally as he can. As Adam Shatz points out in a “New Yorker” profile, cruelty and xenophobia didn’t magically disappear when young Riad moved to a French school—it just changed form. In Syria the kids’ main form of torment was to (inaccurately) label him a Jew, while in France they taunted his high voice and mocked him as gay. “Those experiences gave me an immense affection for Jews and gays,” Sattouf told Shatz.

As dark as Sattouf’s humor sometimes runs, that “immense affection” extends beyond the ostracized, and into the flawed countries and family members he depicts. Many reviewers have noted that Gaddafi and Al-Assad aren’t the only dictators young Riad lives under: he also lives in the shadow of a father with tyrannical tendencies of his own. Yet as he told the “L.A. Review of Books,” “I wanted to put the reader in an embarrassing, awkward position. Sometimes you love the character and say, ‘Oh, he’s nice!’ And other times, you are horrified, because you realize, ‘I am liking this horrifying person.’”

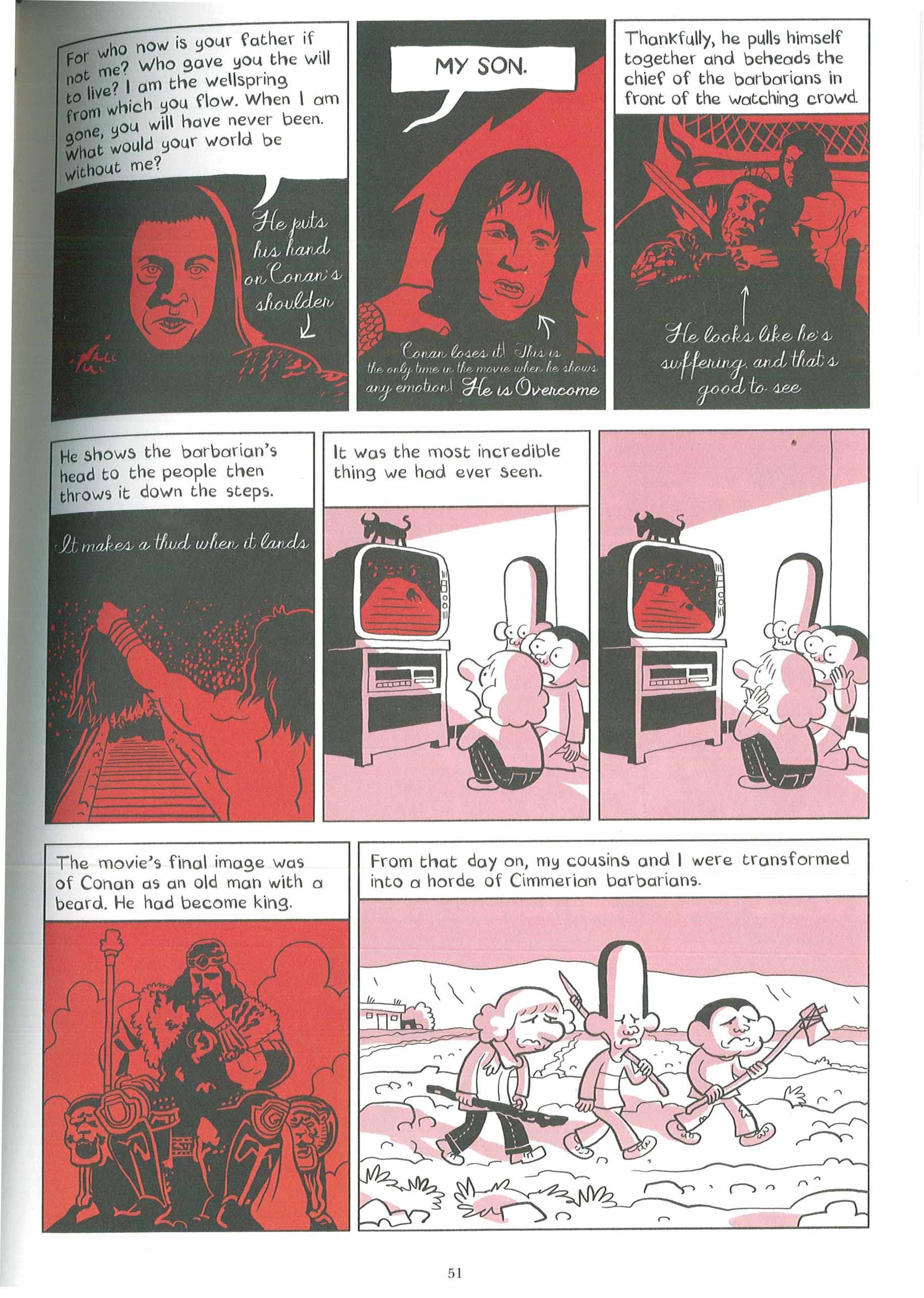

Sattouf, in short, reserves his strongest critique not for flawed individuals, but for the systems that create them. One of the most brutal influences on young Riad and his Syrian cousins in this volume, for example, is Hollywood. They score a copy of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s 1982 melodramatic fantasy “Conan the Barbarian,” and as might be expected of pre-teen boys in a rigidly patriarchal society, they’re transfixed.

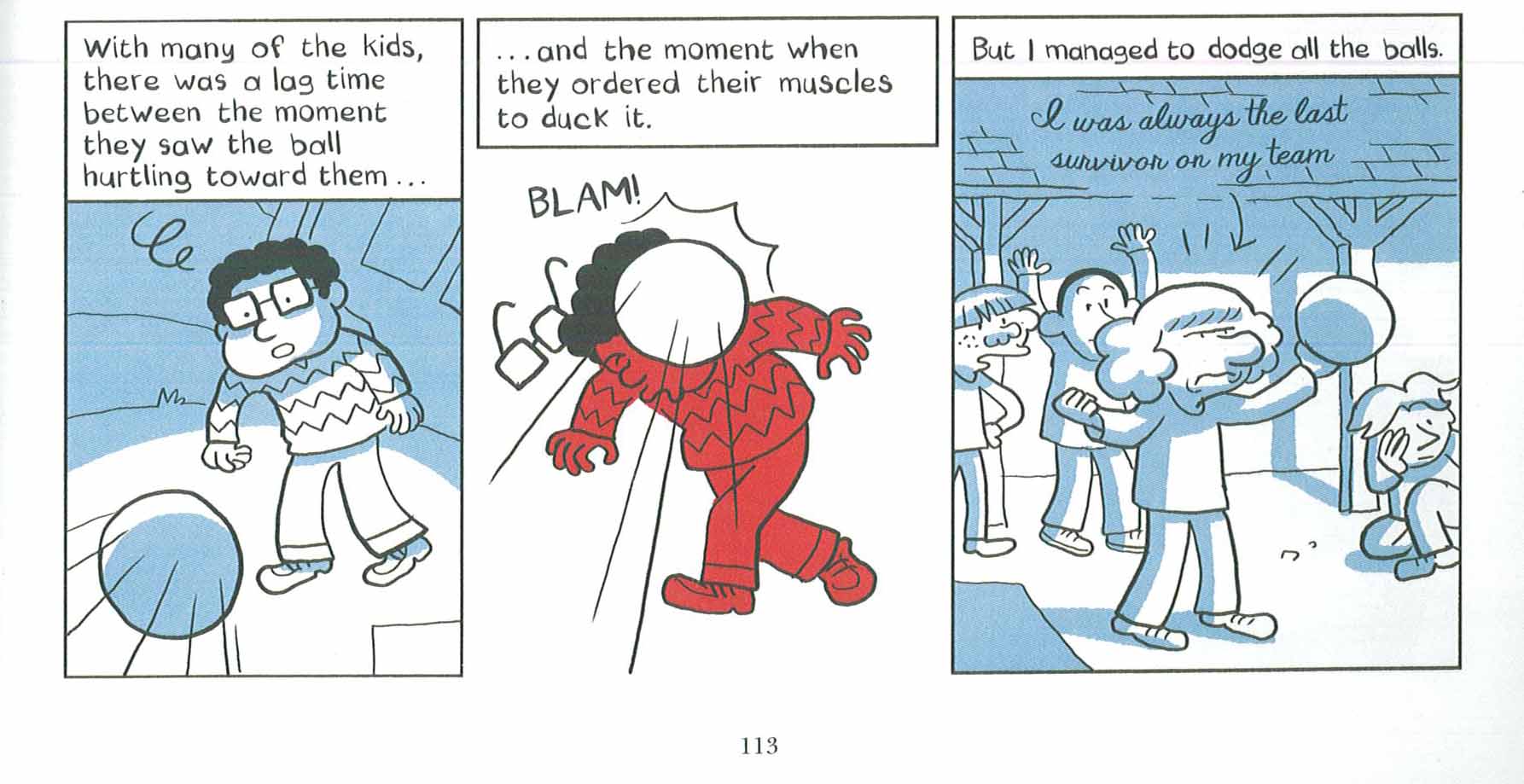

Violence isn’t reserved to Syria or Hollywood, however. Young Riad’s French school sanctions a form of playground violence that many Western readers might recognize:

But lest readers start to think that Riad’s childhood was “just like” her or his own in the U.S., Sattouf jolts us back to systemic problems that young Riad, and especially his mother, can’t fix or even challenge. When Clementine, pregnant with a third child, tells her black-clad Syrian mother-in-law that “this little boy, or girl, is very calm,” the older woman immediately exclaims, “It will be a boy, thanks be to God!” then adds, “Girls are a catastrophe.”

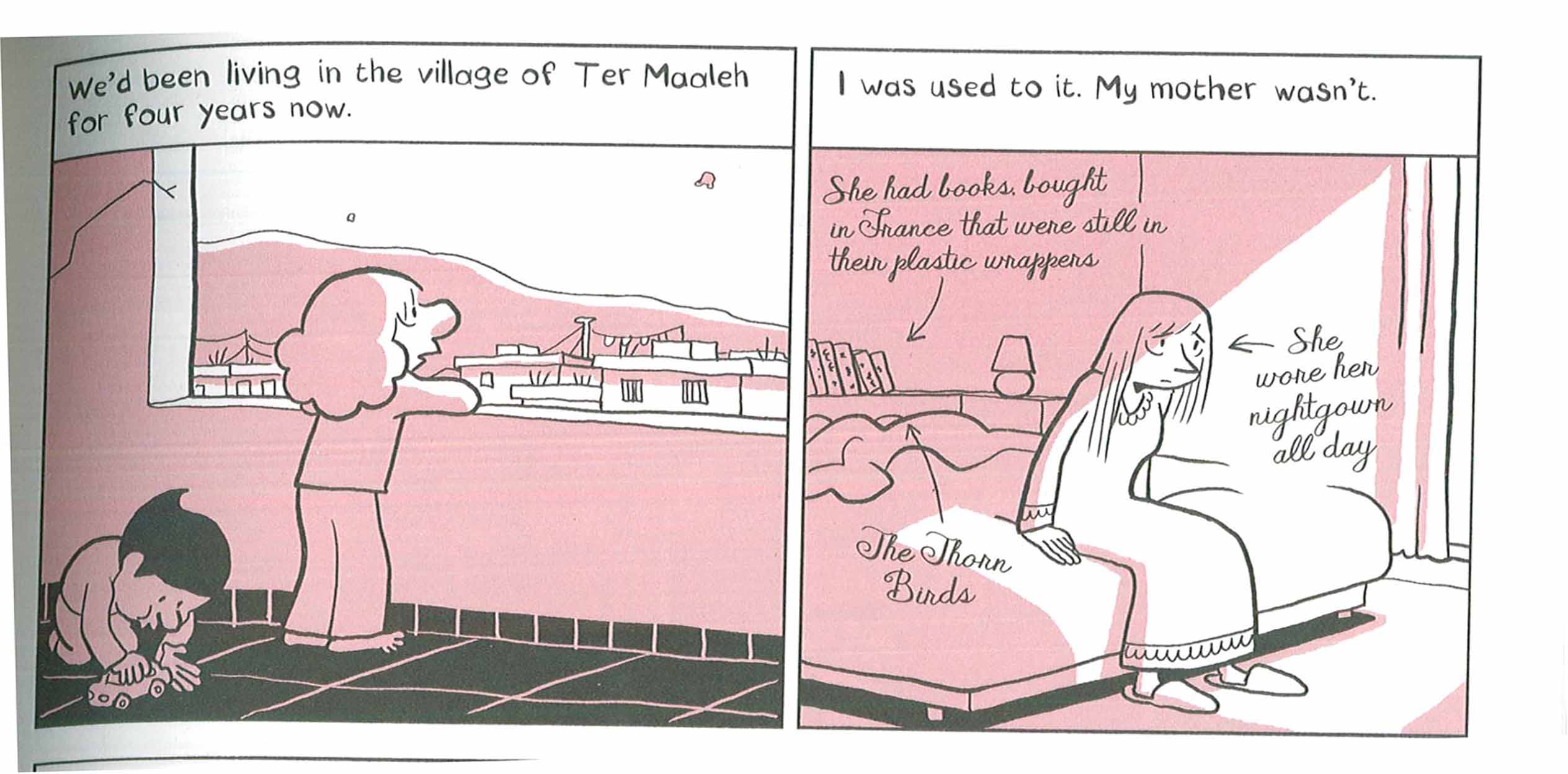

And young Riad’s mom also becomes a catastrophe in this setting:

That airborne plastic bag in the left-hand frame reappears periodically throughout the book. As depicted by Sattouf, Syria’s sweeping views, much like its people, are lovely, but rarely unmarred. Yet it’s precisely such odd but engaging details—is it a bag or a really fat bird?—that pull readers in, keep them reading, and keep them thinking while they wait for volume four.