I was planning on posting my Elkhart Truth archives in a more orderly fashion, starting with the most recent, but in the wake of the news in Charlottesville this morning, this review clearly needs to be prioritized. Stay tuned for a review of March: Book Three.

Thanks to Better World Books, 215 S. Main St. in Goshen, for providing me with books to review. You can find all of these books at the store.

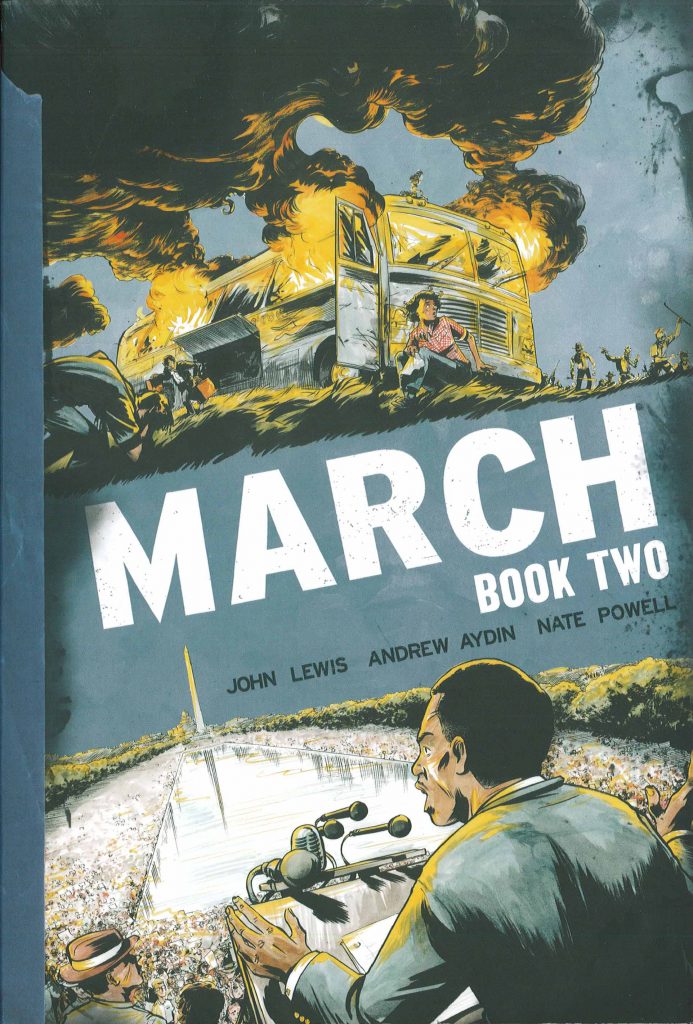

Comics are often associated with violence. Superheroes beat each other up a lot, and war stories, particularly after World War II, have been an especially popular subgenre of comics. There’s plenty of violence in “March: Book Two,” a graphic memoir written by Georgia Congressman John Lewis and his former staffer Andrew Aydin, and illustrated by Nate Powell. The violence is part of the reason why this Young Adult book is classified for older kids, grades 7 to 12. Not an ounce of that violence, however, is gratuitous. Rarely has Common Sense Media—a nonprofit that provides ratings to help parents make smart decisions about the media their children consume—given a book the highest ranking for violence as well as for “Educational value,” “Positive messages,” and “Positive role models.”

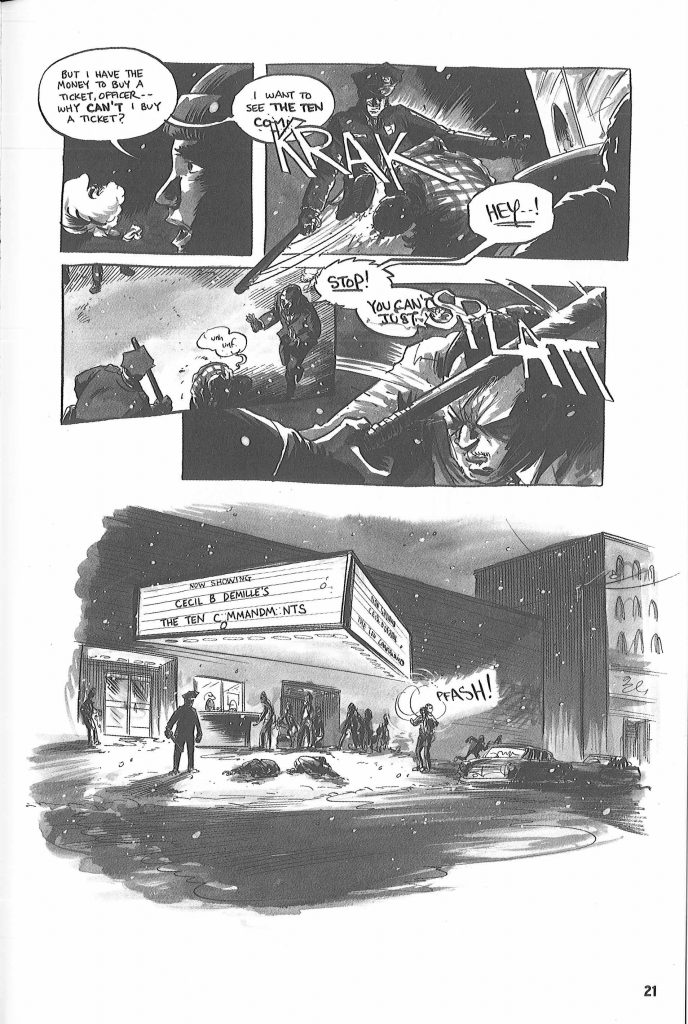

Throughout the book, small but powerful details, like the irony of the film listed on the marquee (The Ten Commandments, if you’re having trouble enlarging the image) pull the careful reader more deeply into the story in a way that only comics can.

If you haven’t yet read “March: Book One,” please do; everyone from Bill Clinton to “Reader’s Digest” put it on their must-read lists for 2013 and beyond. (Check the 2013 archives for my review.)

By no means, however, do you need to read the first installment to understand the second. “March: Book Two” is set mostly in Birmingham, Alabama, beginning in 1961 at the start of the freedom bus rides and ending in 1963 with the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church. That attack killed four young girls and so horrified the nation that many argue it turned the tide of public opinion and cleared the way for the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

But as this book shows, there was plenty of violence to be horrified about well before that church bombing, even if it didn’t all reach the mainstream press. Especially since this book was released in the midst of the national trauma reaching a crisis point in places like Ferguson, Missouri, it might sound like a pretty difficult read. Lewis and Aydin, however, while they skirt none of the ugly realities of this history, also intersperse more hopeful scenes: the whole story is framed, for example, by Lewis at President Obama’s first inauguration.

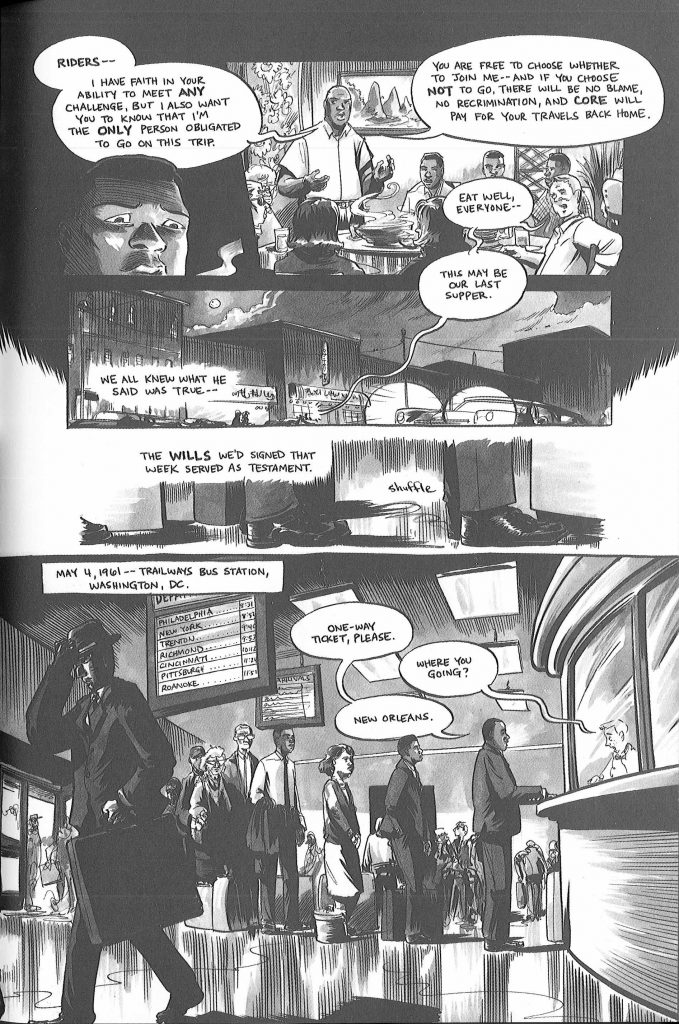

Perhaps most hopeful—and most crucial, especially for the book’s young adult audience—is the way the story highlights lesser-known individual heroes. You don’t need to be Rosa Parks or Martin Luther King Jr. to effect change. You can join small groups of volunteers with a handful of movie tickets as on the above page, or bus tickets, as on this page:

Throughout the book, illustrator Nate Powell keeps the pace fluid across both time and space. Here, Powell pulls the camera way back to show the bus terminal, then zooms in on the feet waiting in line just as readers learn that the “last supper” reference isn’t to be taken lightly. These volunteers have just, quite literally, signed their wills.

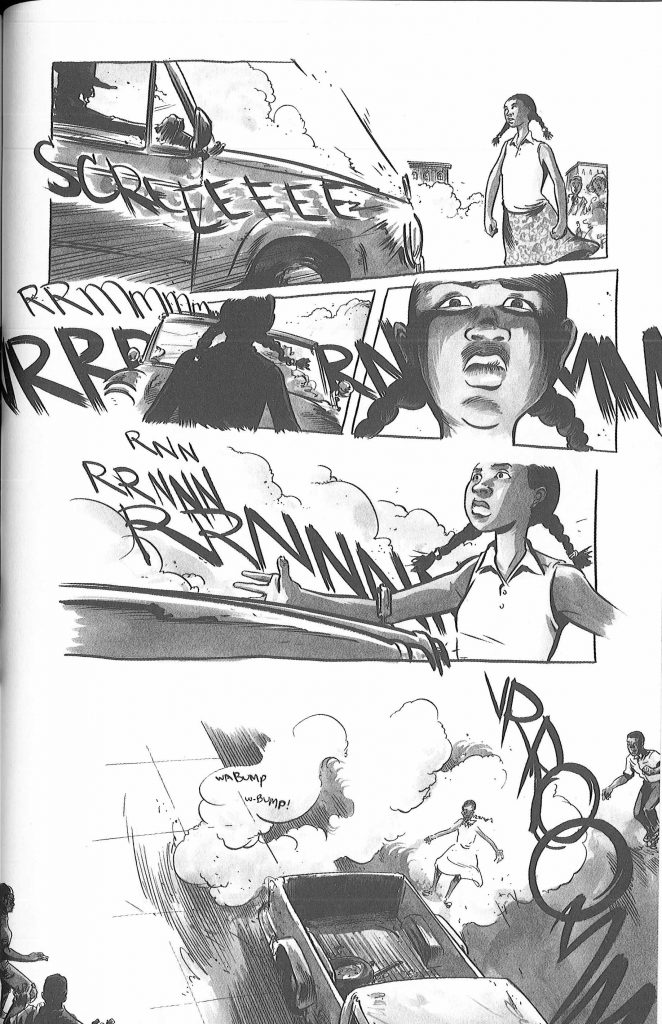

The second installment of any projected trilogy is often muddled. If I had to pick out a flaw with this book, Lewis does such a thorough job of honoring unsung activists that it’s hard to keep track of all the characters. Yet that’s largely the point, of course: it took the whole nation—or at least a majority—to pass the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, and it was the unfamiliar even more than the familiar heroes who made the movement a success. The thirteen-year-old girl below, for example, is one of the protesters trying to desegregate a public swimming pool in Cairo, Illinois in 1962. She refuses to run from an oncoming truck while adults scatter around her.

What Powell doesn’t show is that the truck did knock the girl down, and did injure her—“severely” according to one report. (See this writeup about Cairo on the Civil Rights Movement Veterans website.) Yet the nameless girl lives here as a real-life superhero, unflinching as the dust and exhaust swirl around her, the noise visually separating her—cushioning her, even—from the man running back toward her in that last frame. I half expected her to jump on top of the cab of the truck, grab the driver by his collar, pull him out the window right next to her face, and deliver a powerful, withering line that sets everything right.

But of course superheroes aren’t real, reality isn’t that simple and satisfying, and life—especially for that injured girl and for the many others hurt physically, mentally, or both in their struggles for justice—isn’t fair. “I feel like crying for our country, for our people. How many more times must we go down this road?” John Lewis recently tweeted about Ferguson. He still, however, firmly believes in keeping protest nonviolent. “Violence solely serves the hungry beast of oppression,” he remarked in a later tweet.

As both installments so far of “March” make clear, when it comes to Civil Rights protest, nonviolent doesn’t mean weak or ineffective. As Lewis insisted in a 2014 CNN interview, “Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. inspired me to find a way to get in the way, and to get in trouble. And as a young child, I got in good trouble, necessary trouble.”

Lewis is still getting in trouble, too. As I noted in my review of “March: Book One,” he was most recently arrested for the 45th time (he thinks—he’s lost count) at a protest for immigration reform. “My advice would be simple, “he recently told a young activist fighting for same-sex marriage rights: “You speak out and continue to agitate for what you believe in! Don’t ever run away from a fight.”

Here’s hoping that Lewis, like King and Parks and so many others before him, inspires more people, no matter their age, to dedicate themselves to civil rights for all citizens.