A version of this post was originally published in the “Elkhart Truth” in August or September of 2014. Volume Six of “Sunny” was released in November 2016 to complete the series.

Thanks to Better World Books, 215 S. Main St. in Goshen, for providing me with books to review. You can find all of these books at the store.

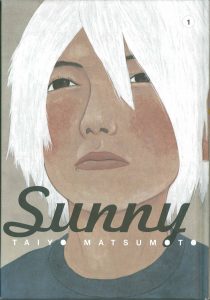

Not much is sunny at Star Kids Home, the Japanese foster home where Taiyo Matsumoto’s “Sunny” is set. This series is much closer to “Little Orphan Annie” than to “Sesame Street,” but without either the wealthy benefactor or the clear-cut villains. Most of the young residents of Star Kids Home have living parents unable to care for them, but for unexplained reasons.

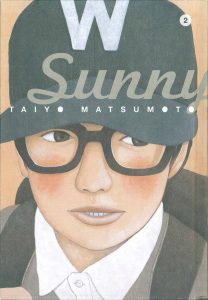

Sunny is a broken-down car in a nearby yard, the kids’ only form of “travel”: they imagine the Sunny (a Japanese nickname for a Datsun) as a spaceship or getaway car, and imagine themselves as heroes, heroines, dashing or deadly outlaws, and sometimes just grownups or kids with happy families. Some of the scenarios the kids dream up are pretty run of the mill, and some—as in the image below—get a bit trippy, but all are complex and deeply affecting, throwing life a bit off balance so we can see it with new eyes.

“Sunny,” published in the US by Viz Media, is a type of comic called “manga,” which basically means comics from Japan. In the US, most manga is directed toward teenagers, with very specific categories for boys (seinen) and girls (josei). There are many complicated subcategories—“Sunny” has also been categorized as “slice of life” manga—but the simple truth is if that you set a typical teenager loose in a bookstore, not only will said teenager know how to find the manga, she’ll also probably sit right down on the carpet and start reading.

That said, “Sunny” has become a crossover hit in the US not only for older readers, but for readers usually more interested in graphic novels than in manga. Volume One of “Sunny” made the “best of” list for 2013 on Salon.com and won a cartoonist’s prize from “Slate.” Author Taiyo Matsumoto has won an Eisner award—the Pulitzer for comics—for his earlier work translated into English. I’ve only so far read Volumes 1 and 2 of “Sunny,” but Volume 3 is now out in English, and 4 is due out this fall.

Unless you’re already a fan of manga, you might find “Sunny” disorienting at first, especially because manga reads from right to left. Not only do you open the book from the “back” and turn the pages the “wrong” direction, but the layout of each individual page is “backwards” as well.

As you might guess, translating manga from Japanese to English involves more than just moving the binding to the other side: if it’s done well, it requires a substantial redesign, and even then, translations of dialect and other subtle details often don’t come across.

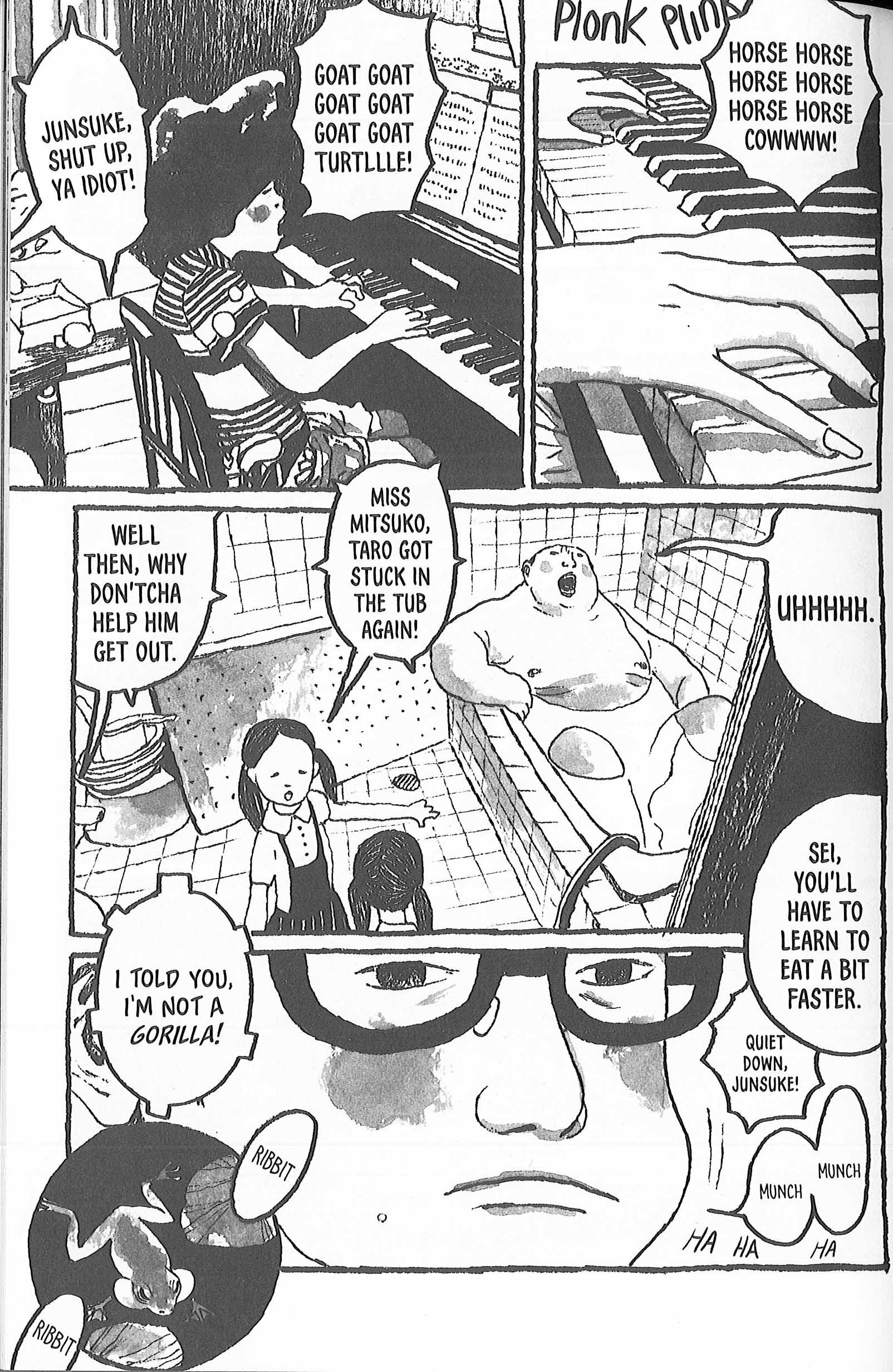

But part of why manga fans are so devoted is that they enjoy the challenge of decoding visual elements that don’t translate easily into English. Readers of American comics, for example, are all pretty familiar with the idea that bubbles leading up to a word balloon signifies thought, while a pointy tip coming out of a word balloon signifies that the words are spoken aloud. Multiple points usually mean multiple speakers, but that logic doesn’t seem to work in scenes like this one:

I read more graphic novels than manga, so I was confused for a while, too, but finally figured out that the spikes on those bubbles represent shouting, anxiety, or both. In general, as you can tell from the above images, “slice of life” manga is slower and more atmospheric than Western comics, less concerned with assigning speech than with representing its tone and presence. Manga even has a sound effect for silence, “shin,” which can be stretched across a frame or a page as “shiiiiiin.”

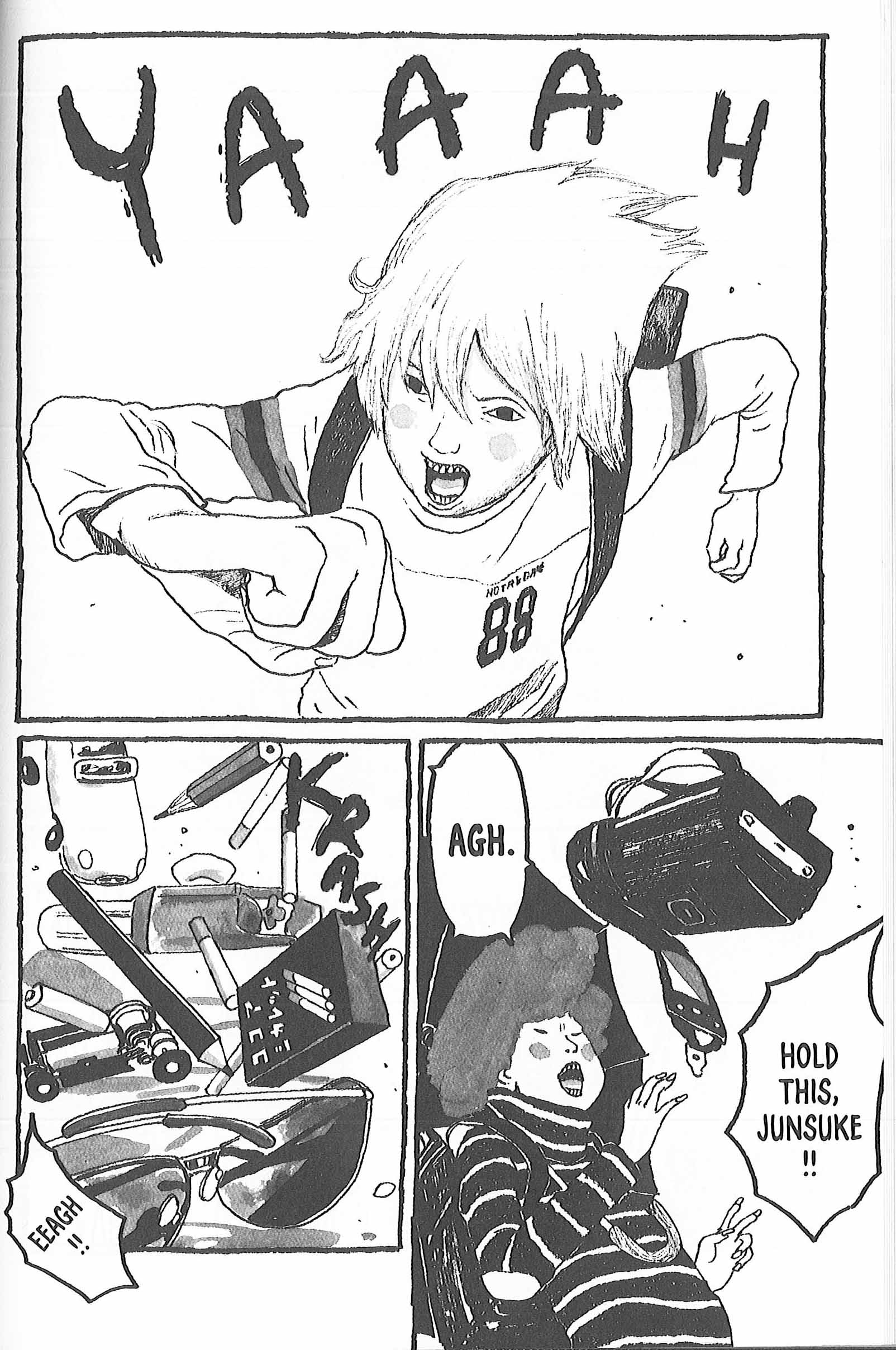

Don’t let all of my explanation give you the impression that “Sunny” is a difficult read. This is a character-driven series, and Matsumoto’s complex characters are much more familiar than foreign. The kids at Star Kids Home struggle with their outcast status at school, miss their parents, and develop crushes just like typical American teenagers. And Michiana readers, check out what college this character’s shirt is from—how’s that for familiar?

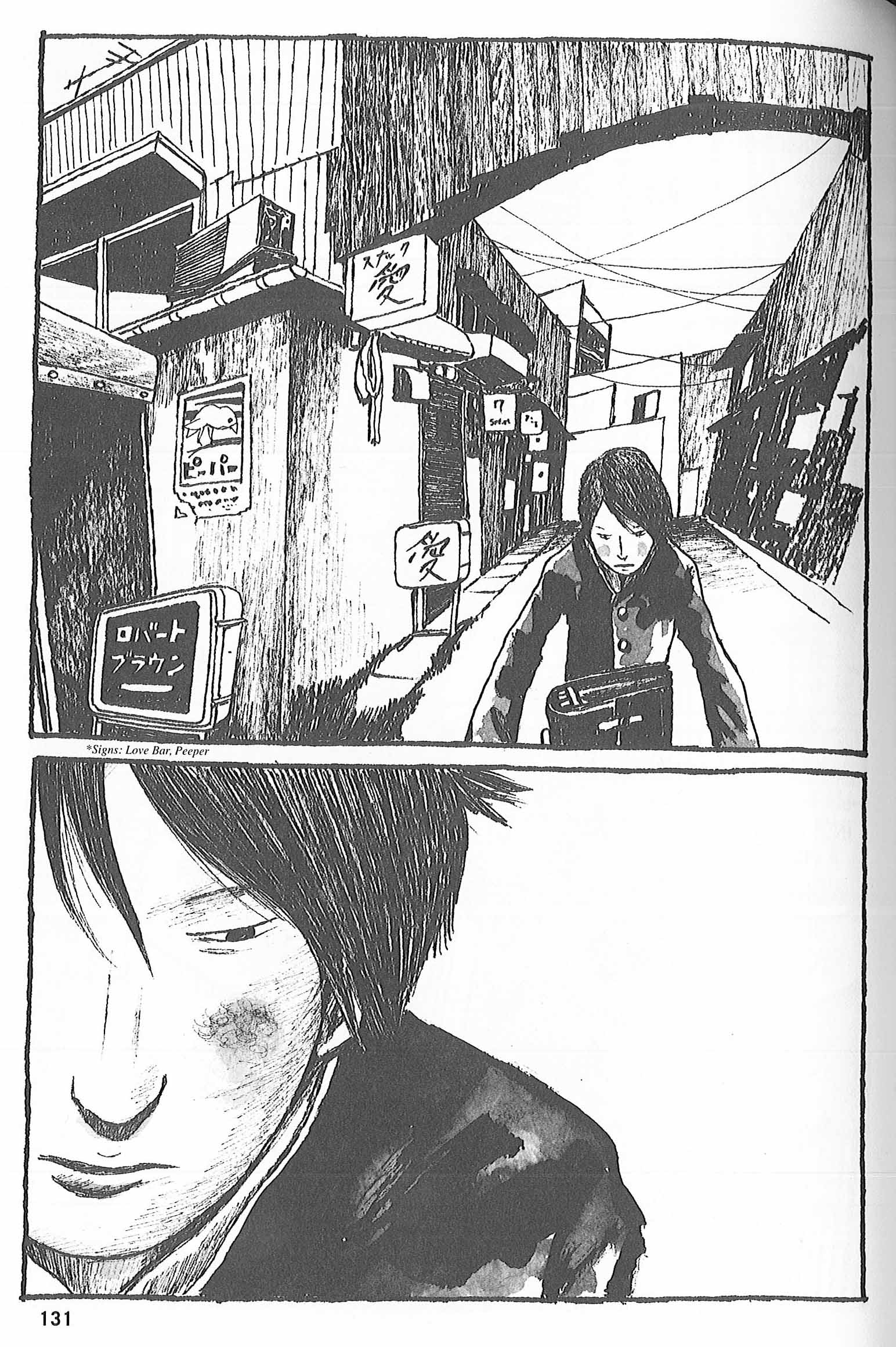

The US edition of “Sunny” was translated by Michael Arias, an acclaimed expat producer of Japanese cartoons, or anime. Arias’s cross-cultural expertise strikes an expert balance between the foreign and the familiar. In the image below, for example, no matter what culture you’re from, you’ve felt like this character at least a handful of times in your life. But as Western readers, the unfamiliar streets and lettering on the signs—translated in subtle, small-print footnotes—help us feel like we’re traveling somewhere new.

Couple this emotional and narrative depth with hand-drawn illustrations—Matsumoto is one of a handful of holdouts who doesn’t use computers—and “Sunny” represents the best use of comics as a genre: not just an illustrated story, but a story that creates sparks out of the friction between words and images.

Matsumoto himself grew up in a foster home, and although he’s made it clear that “Sunny” is more fiction than memoir, the truth behind these characters makes them shimmer on the page. “When I’m drawing something that actually happened, it’s like the child on the page really exists,” Matsumoto said in a 2013 “Timeout Tokyo” interview. “I’ll draw a scene of a child crying, and I’m not sure if it’s the child crying or if it’s me.” Throughout “Sunny,” the author, his characters, and the readers are all transported somewhere both unexpected and familiar, somewhere they recognize but have never been before—like life, no? Just as in the best literature, no matter the genre.