An earlier version of this essay ran in the “Elkhart Truth” in September 2014. The “Luke on the Loose” storyline is a good fit for Father’s Day. Thanks to Better World Books, 215 S. Main St. in Goshen, for providing me with books to review. You can find all of these books at the store.

As a comics devotee, I spend a lot of energy trying to convince people that comics aren’t just for kids—but of course many, many comics are intended for kids in the first place, even when adults enjoy them too. When done well, kids’ comics can strengthen young readers’ tools for interpreting both words and images, and help them develop reading and critical thinking skills crucial to navigating our visually complex society.

I usually review publications less than a year old, but in celebration of the recent creation of TOON Graphics, a new division of TOON books, I’m reviewing two of my preschool-age sons’ favorite books from TOON—practically their favorite books, period—“Luke On the Loose” (2008) and “Benjamin Bear in Fuzzy Thinking” (2011).

My sons are 4 and 2, so they’ve got a ways to go with their reading skills. But listening to my four-year-old describe complex visual puns and sound out background noises from these comics has convinced me that the popular belief that comics hinder reading skills is—to say it nicely—a load of hooey.

Françoise Mouly, founder of TOON books for kids, is art editor of “The New Yorker,” as well as wife of —and comics co-conspirator with—Art Spiegelman. Spiegelman wrote “Maus,” the seminal comic for grownups, and arguably the comic that sparked the recent popular explosion of highbrow comics, sometimes called graphic novels. (If you’ve read “Maus,” Mouly is Art’s partner, the mouse in the striped shirt. If you haven’t read “Maus,” please do! Now!)

Mouly founded TOON in 2008, inspired by the struggles of her youngest son Dash, who didn’t take to reading as easily as his older sister had. Mouly grew up in France, so the family’s Manhattan apartment was full of French and other European comics for kids (think “Tintin” and “Asterisk”), which Dash loved. When Mouly searched for similar books in English to balance Dash’s video games with some reading, however, she had trouble finding an equivalent.

Mouly herself used comics to learn English when she moved from Paris to New York City in the mid 1970s. She soon teamed up with Spiegelman to start “RAW,” a comics anthology that collected and published European and underground comics in an effort to raise the profile of comics in the US. With issue titles like “The Graphix Magazine for Damned Intellectuals” and “The Graphix Magazine that Lost Its Faith in Nihilism,” “RAW” was clearly not for kids. But after having kids of her own, Mouly began a RAW Junior division, which published original comics for kids in an anthology called “Little Lit.” (Goshen readers, both the Goshen Public Library and the Goshen College library have the “Little Lit” series. Check them out!)

For TOON, Mouly recruits talent from the world of comics—“Sandman” creator Neil Gaiman is scheduled to release a TOON version of Hansel and Gretel in October—as well as the world of children’s books. Harry Bliss, author and illustrator of “Luke on the Loose,” is best known in kid circles as the illustrator for the series that began with “Diary of a Worm.” He is also an artist for the “New Yorker,” but this is his first full-length solo comic.

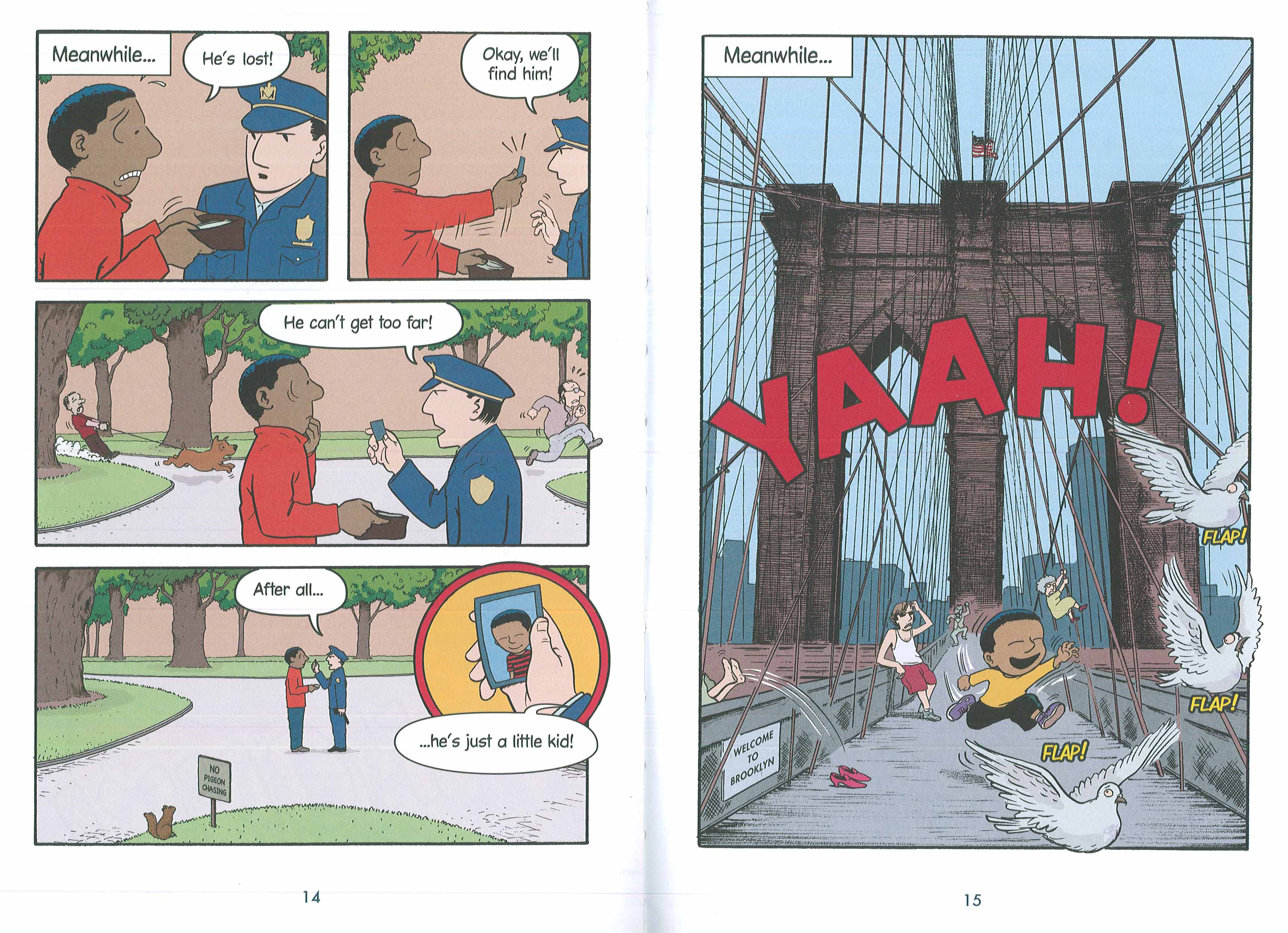

The story is simple, but it quite literally jumps out of the frame:

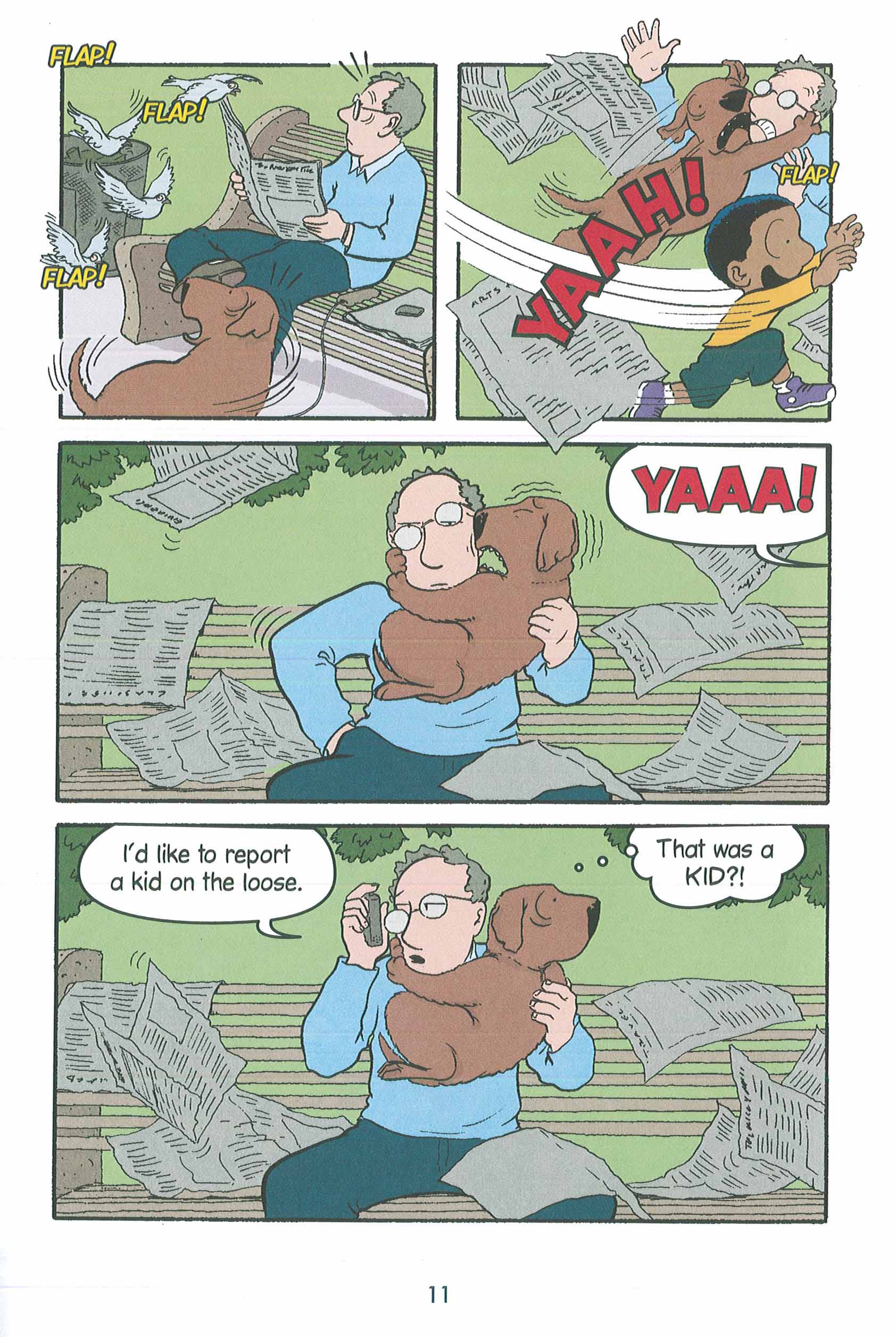

As Luke continues his pigeon chase across New York City, a pigeon-wing “Flap!” or two visually foreshadows each of Luke’s disruptions, like a gleeful version of those two ominous notes that build up attacks in the movie “Jaws.” Bliss’s use of frames to play with pace and comic timing make “Luke” more than an illustrated children’s book. For kids, learning to read comics like this requires multiple simultaneous levels of interpretation.

Kids love to read and reread, picking out new details each time, like the “no pigeon chasing” sign in the corner when Luke’s dad talks to the police officer. Even subtler simple details like the above man’s calm extraction of his cell phone and his slightly crooked glasses mark Bliss as a pro on the level of Charles Schulz and “Peanuts.”

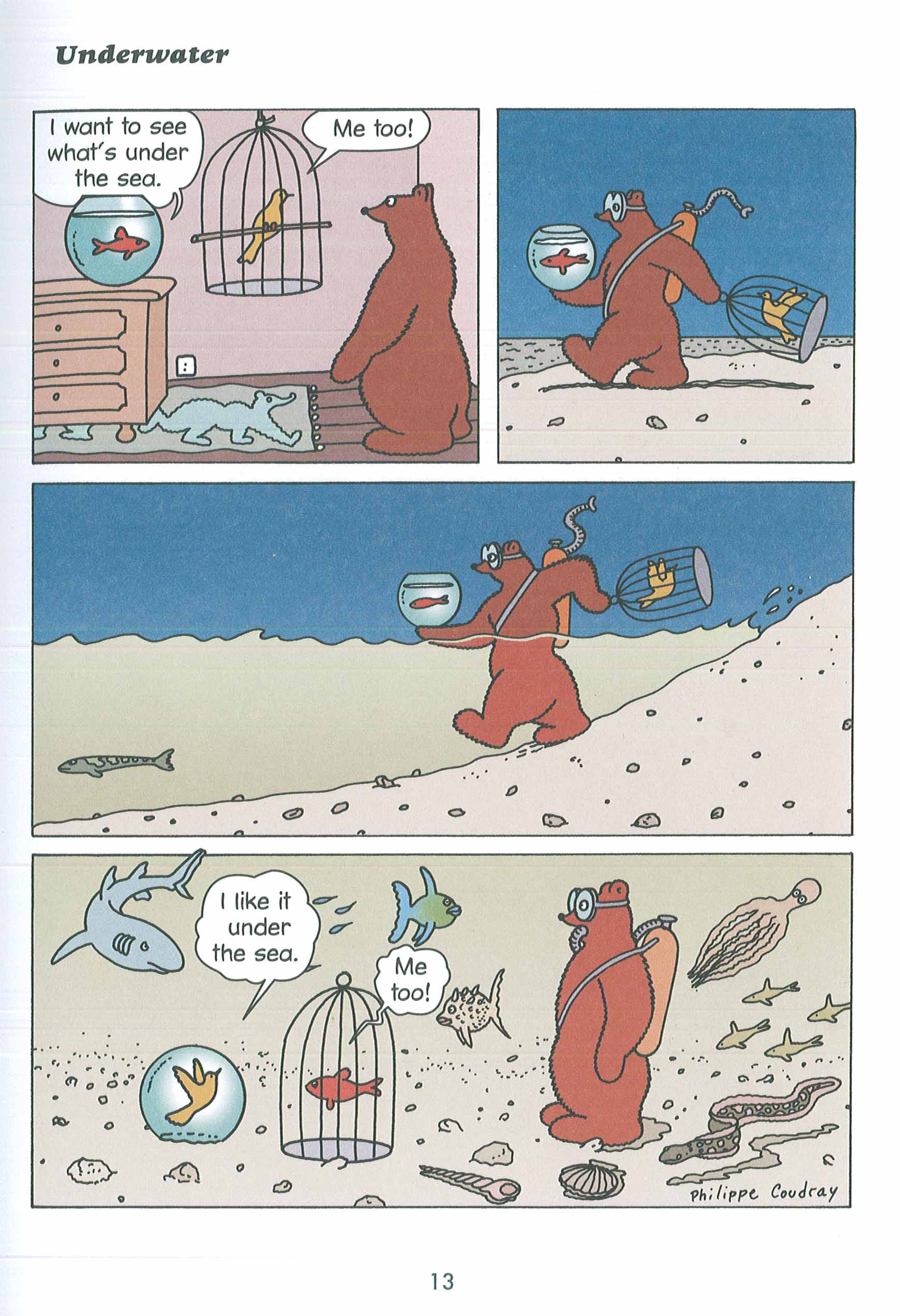

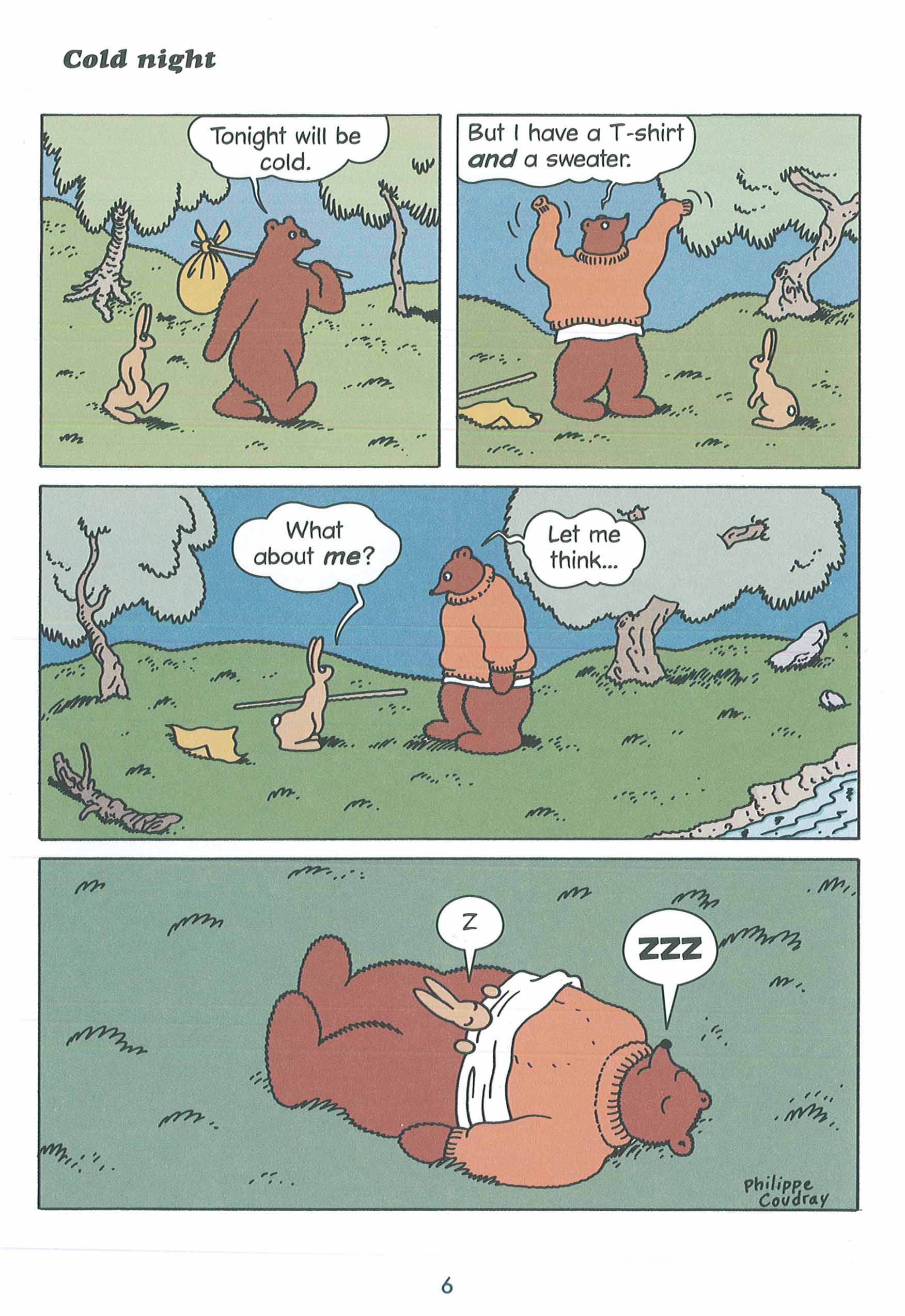

The stories in “Benjamin Bear” are much shorter—most take only a page—but also much more intellectually complex. My kids love to puzzle them out.

Comics like this encourage kids to delve into their vocabulary to articulate what they don’t understand. They also encourage parents to practice more complex communication with their kids. I especially love revisiting these books with my boys every few months to gauge how much more they “get” each time—their brains are developing so fast, it’s fun to track the progress. This one, for example, my older son is still trying to figure out.

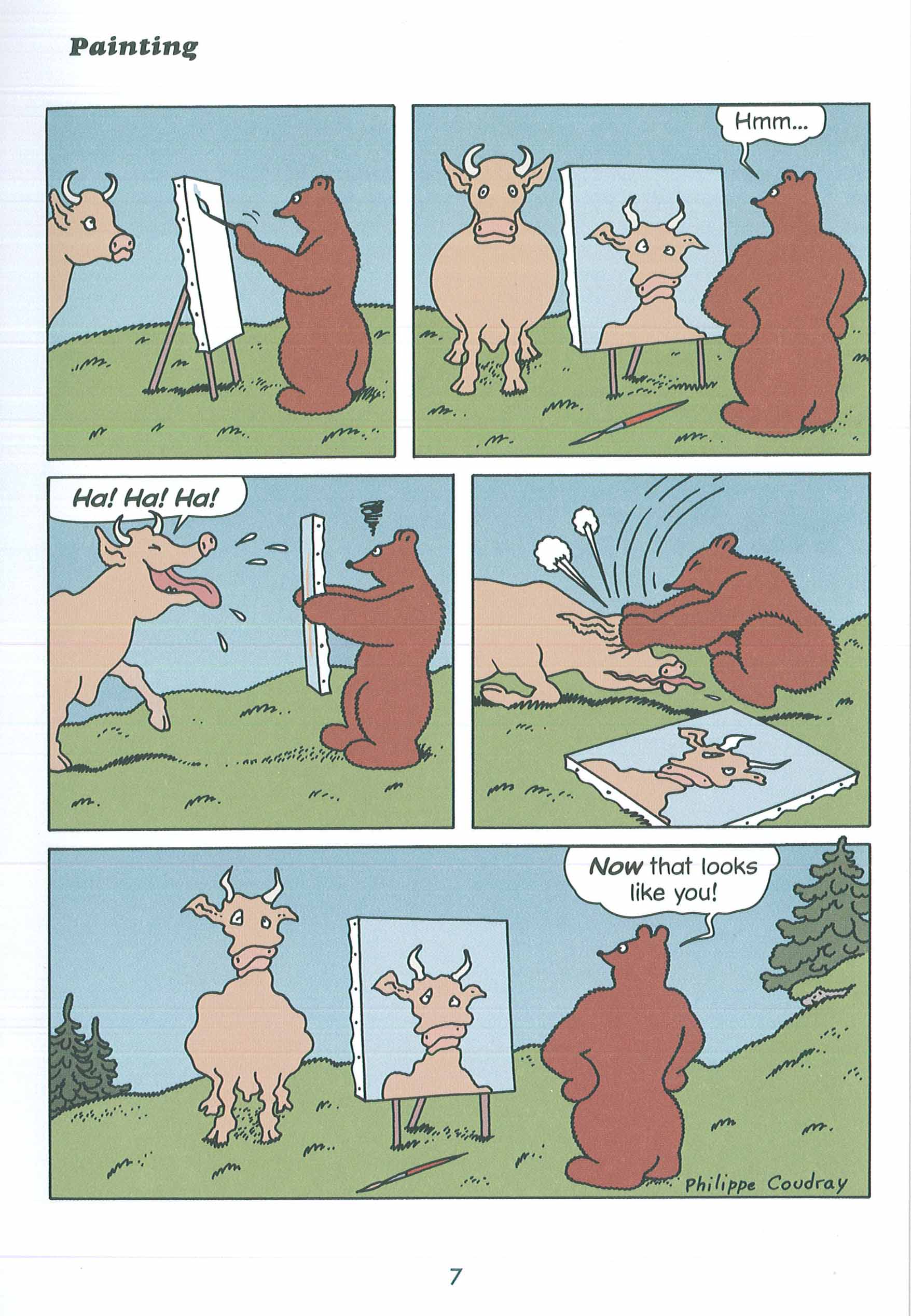

Okay, okay, this particular example does fuel the stereotype that comics are violent. Really, though, compared to the local TV news? And the vast majority of “Benjamin Bear” is just plain sweet:

Each TOON book comes with an appendix of tips for reading comics with kids, and the website is packed with materials for educators, including guides for Common Core instruction.

In a recent interview for “The Rumpus,” Mouly explained her dedication to TOON books: “With TOON, I’ve had moments that brought tears to my eyes, like a teacher saying, ‘I teach in this really difficult school district, where the kids have no support at home, but the kids love these books.’ . . . Don’t be suspicious of something just because kids love it,” she told the “New York Times” last month. They—the kids and the comics both—might have something to teach you, too.