In late October, I’ll be reviewing “The Dragonslayer,” a TOON Graphics collection of Latin American folktales by Jaime Hernandez. If you’re not familiar with Hernandez, he’s a massive figure in the U.S. literary scene. Here’s a bit more context in an post from December 2014, the early days of Commons Comics at the “Elkhart Truth.”

Thanks to Better World Books, 215 S. Main St. in Goshen, for providing me with books to review. You can find all of these books at the store.

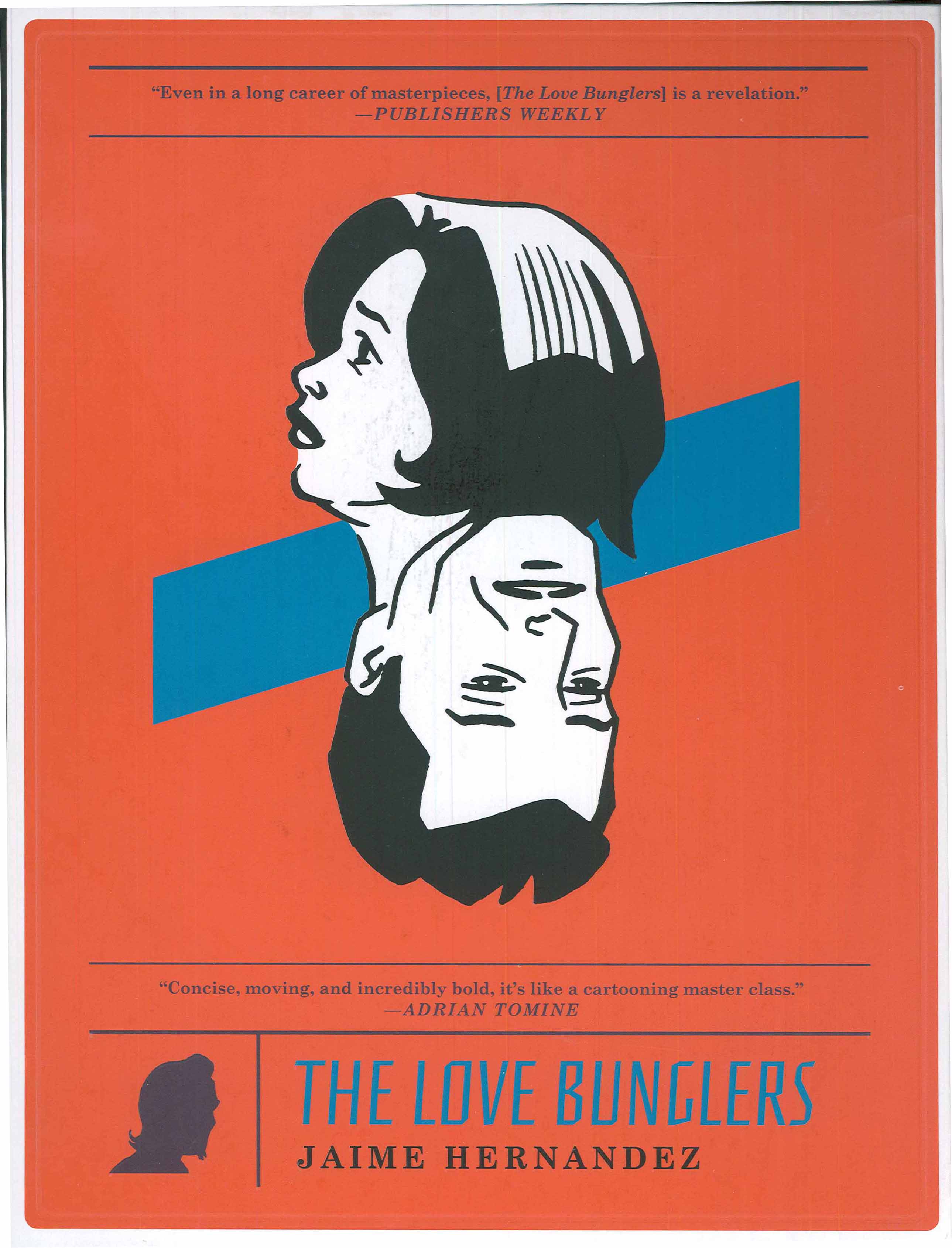

I’ve been reviewing a lot of young adult books here on Commons Comics since it moved to the “Truth” back in August, partly because I’m wary of breaking into comics that put the “graphic” in “graphic novel.” But this reluctance means that I’ve been neglecting a seminal subset of work that makes comics great. So, fair warning: Jamie Hernandez’s new collection “The Love Bunglers” contains nudity, offensive language, and a sex scene. Don’t buy this book for young kids as a holiday gift. But please also don’t dismiss this brilliant work because of a couple of pages that show adults being adults.

Critics have been gushing about “The Love Bunglers” since it first appeared in serial form in 2011. Most of these critics have been following the characters in this book since the early 1980s in the series “Love and Rockets,” which was written by Jamie and his two brothers, Gilbert and Mario. “Love and Rockets” has continued for over thirty years, and both Gilbert and Jamie continue to write and draw individual successful spinoffs. Gilbert’s stories are set mostly in Mexico, while Jamie’s are set mostly in L.A. Their sprawling and complex cast of characters travels in and out of powerfully realistic storylines that dip into magical realism, science fiction, and soap opera.

Don’t worry: if you’re not familiar with “Love and Rockets,” or even with comics in general, you can still appreciate “Love Bunglers.” I’ve only dabbled in the series, but I was still profoundly moved by this stunning and beautiful book about the human experience. As for those who have been following these characters closely for thirty-plus years—well, let’s just say that I’ve never heard so many grown comics nerds publicly admitting in their reviews that this book reduced them to tears.

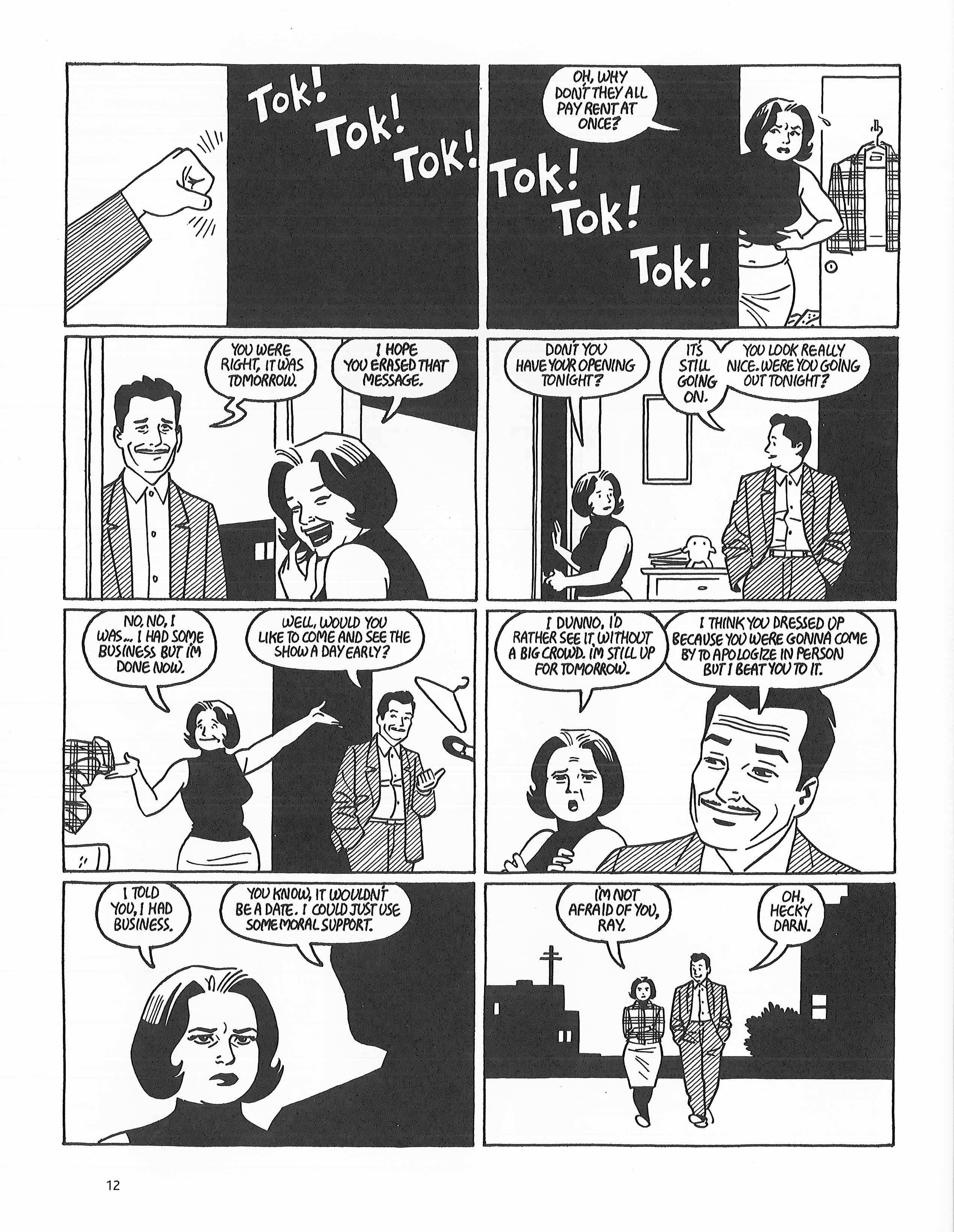

The two “love bunglers” referred to in the title and pictured on the cover are Maggie (Perla) Chascarillo and Ray Domingez. These characters have been orbiting each other since they were teenagers. For readers first encountering them, Ray comes across as sweet and a bit paternal, protective of Maggie.

The attraction in their relationship flips back and forth, as it has for over thirty years: we see Ray attracted to Maggie, Maggie attracted to Ray, both characters pretending otherwise and chasing after other people. Readers seeing these characters for the first time might be somewhat mystified: Maggie looks like a pretty ordinary middle-aged woman with a pretty ordinary job running an apartment complex. She’s no age-defying superhero—yet her old flames still circle around and yearn for her, even as readers see her struggle with her own foibles and insecurities.

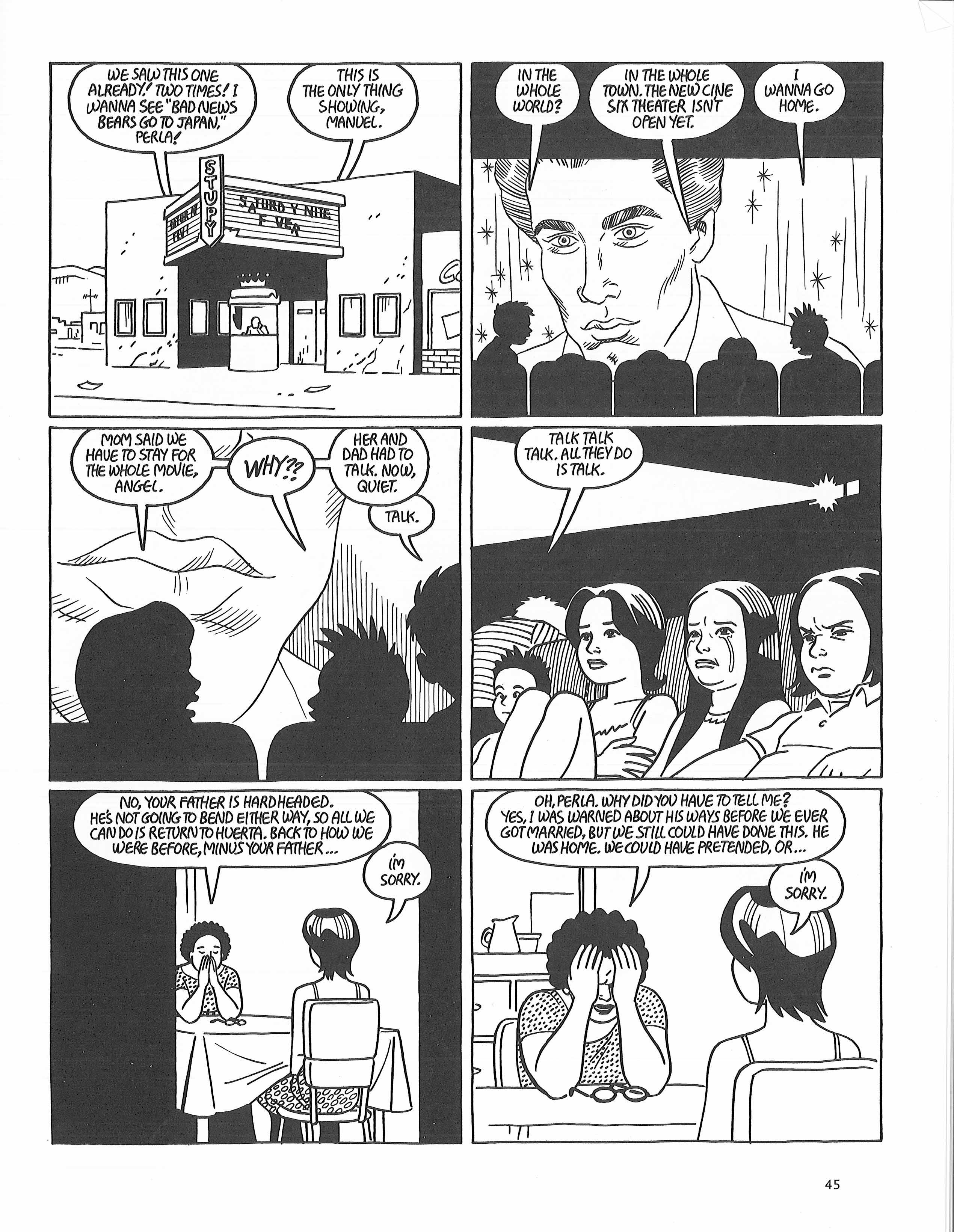

Hernandez has been hinting since the series began that Maggie has a complicated family backstory. We finally see in “The Love Bunglers” what happened when the Chascarillo family briefly moved from California when Maggie (then known as Perla) was young: an awful lot. I won’t give away any plot here, but this scene mixes a healthy dose of pop culture into Maggie and her siblings’ processing of their parents’ breakup:

What do John Travolta and “Saturday Night Fever” have to do with a Mexican-American family finding their way into the American Dream? A lot more than you might think, especially if you recall more about the film than Travolta’s iconic white suit and famously silly disco pose. Those glimpses of Travolta in the background spark complex connections between Maggie’s family and the struggling east-coast urban Italian American family in the film.

If that level of analysis seems like a stretch, on a more straightforward level, the scene still reminds readers—gracefully, in one frame at the top of the page—just how little guidance these kids had from adults in their family and neighborhood (“Saturday Night Fever” was rated “R” for a reason). This realization makes the mom’s dialogue at the bottom of the page especially painful to witness. Maggie was doing the grownup responsible thing—telling her mother that she saw her father doing something wrong—and she’s forced to apologize for it. No wonder she grows into a “bungling” adult, questioning her own instincts and her very identity.

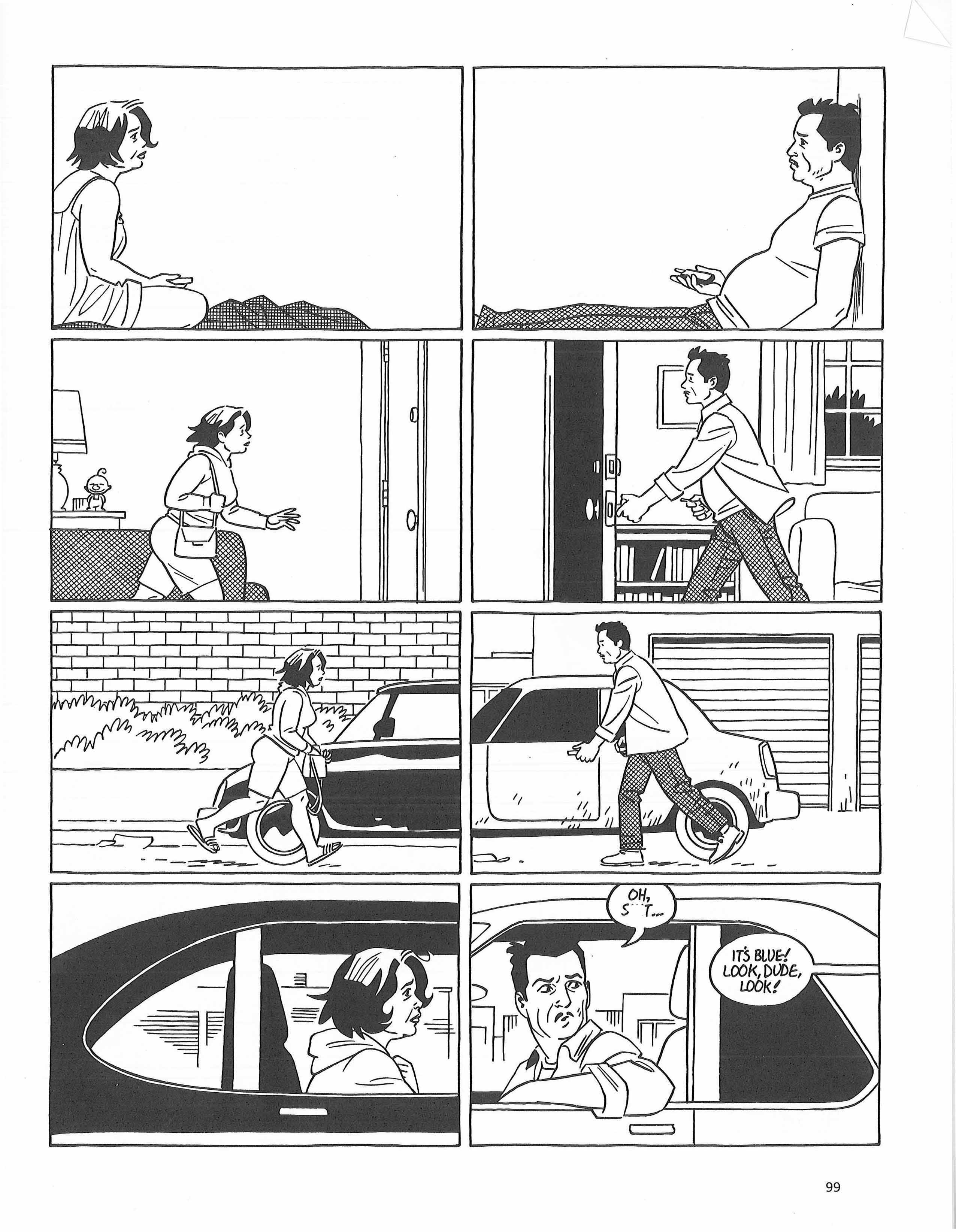

This level of character background and complexity is what led Pulitzer-prize winning author Junot Diaz to claim in a recent interview on KCRW in Los Angeles that “American fiction is [still] catching up to ‘Love and Rockets.’” Yet comics is a different medium than word-based fiction, as the crescendo of the book’s last few pages especially convey.

Do they finally reach each other? I don’t want to ruin the plot for you, but I do want to emphasize how well comics frames mimic memory and the fragmented way our brains construct our lives and histories. I may have had to edit the “adult” language from the frames above, but the language in this book is realistic and sincere, not gratuitous. “The Love Bunglers” is comics as literature, pushing the boundaries like James Joyce or Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and resisting the simplest, most satisfying endings for the sake of exploring the looping, sometimes dead-end, but always intense unpredictability of real life.