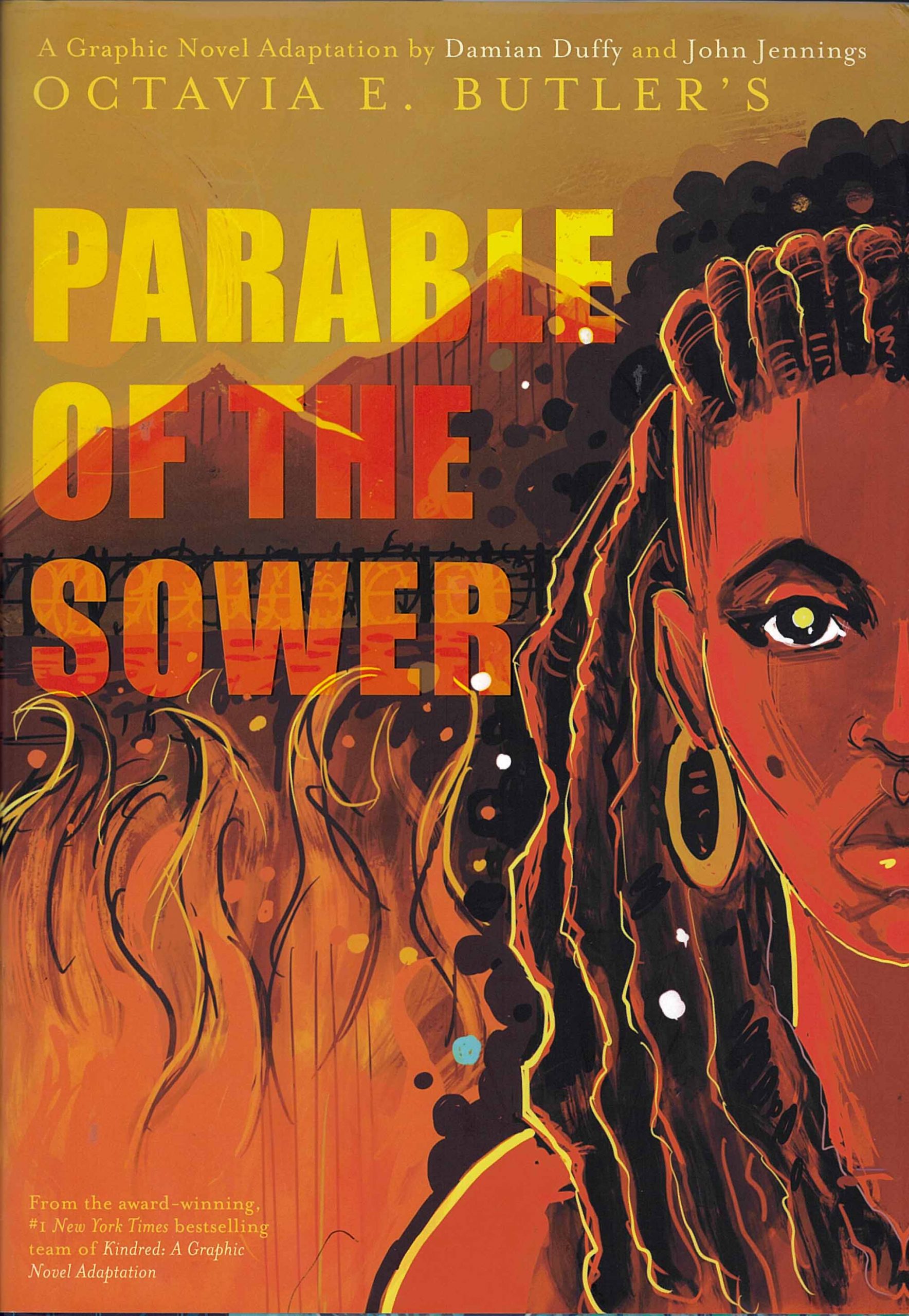

“Parable of the Sower,” by Octavia Butler. Adapted by Damian Duffy and John Jennings. Abrams Comics Arts, January 2020. 266 pp. Paperback, $24.99. Recommended for ages 15 and up.

Thanks to Fables Books, 215 South Main Street in downtown Goshen, Indiana, for providing Commons Comics with books to review.

COVID-19 UPDATE: Fables is back open! Please enter through the back and follow store guidelines. High risk customers can still make browsing appointments before or after hours, and all customers can continue to order online at fablesbooks.com, over the phone 574-534-1984, or via email fablesbooks@gmail.com.

In the intricately imagined worlds of the late science fiction writer Octavia Butler, apocalypse is nothing new, whether triggered by aliens, viruses, or disintegrating social and political structures. Butler isn’t for everyone. She was the first science fiction writer to win a MacArthur “genius” grant, yet some have found her work too stylistically direct, too political, or both. As the years have passed since the publication of her 1993 novel “Parable of the Sower,” however, she’s looking more and more like a prophet.

Yet Butler, who died in 2006, refused that role. In a 1998 address at MIT, she called “Parable of the Talents,” the sequel to “Sower,” “a cautionary tale, although people have told me it was prophecy. All I have to say to that is: I certainly hope not.”

Lauren Olamina, the teen protagonist of “Parable of the Sower,” is a reluctant prophet herself. The story is told from Olamina’s journals, part of which sound like any literary-minded teen’s journal might in the face of apocalypse—Anne Frank’s diary comes to mind—but part of which also records a new gospel Olamina has named “Earthseed,” which she feels driven to set to paper as the world around her becomes increasingly violent, desperate, and unpredictable.

I won’t pull any punches: Butler’s story is largely bleak, and writer Damian Duffy and artist John Jennings’s adaptation sometimes proves gruesome. If you’re in a fragile emotional state about the world right now, I recommend you put this book aside for another time. As Jennings himself put it in a recent interview in “Publisher’s Weekly,” “Parable of the Sower” “outhungers ‘Hunger Games’; that’s ‘Little Bo Peep’ compared to this.”

That said, Duffy and Jennings, who won an Eisner award in 2018 for their graphic novel adaptation of Butler’s novel “Kindred,” have created the most beautiful apocalypse I’ve ever seen:

“Sower” is set in 2024. When Butler first wrote the story in 1993, this was more than 30 years in the future. As if it’s not difficult enough to be a teenager in apocalyptic times, Olamina also has “hyperempathy syndrome,” which causes her to feel other people’s pain and pleasure as well as her own, and which proves an especially unfortunate affliction as she attempts to navigate a dangerous landscape scourged by high death rates.

Olamina’s disease seems connected to her creative drive, however, which helps her develop the tenets of her clear-eyed religion. As we learn from Olamina’s notes, interspersed with her journal entries, the main rule of her “Earthseed” gospel is to embrace change. Only fifteen as the story opens, Olamina resolves to harness the power of change and remain purposeful and unflinching where her elders falter. Here, she listens to her parents arguing in the next room:

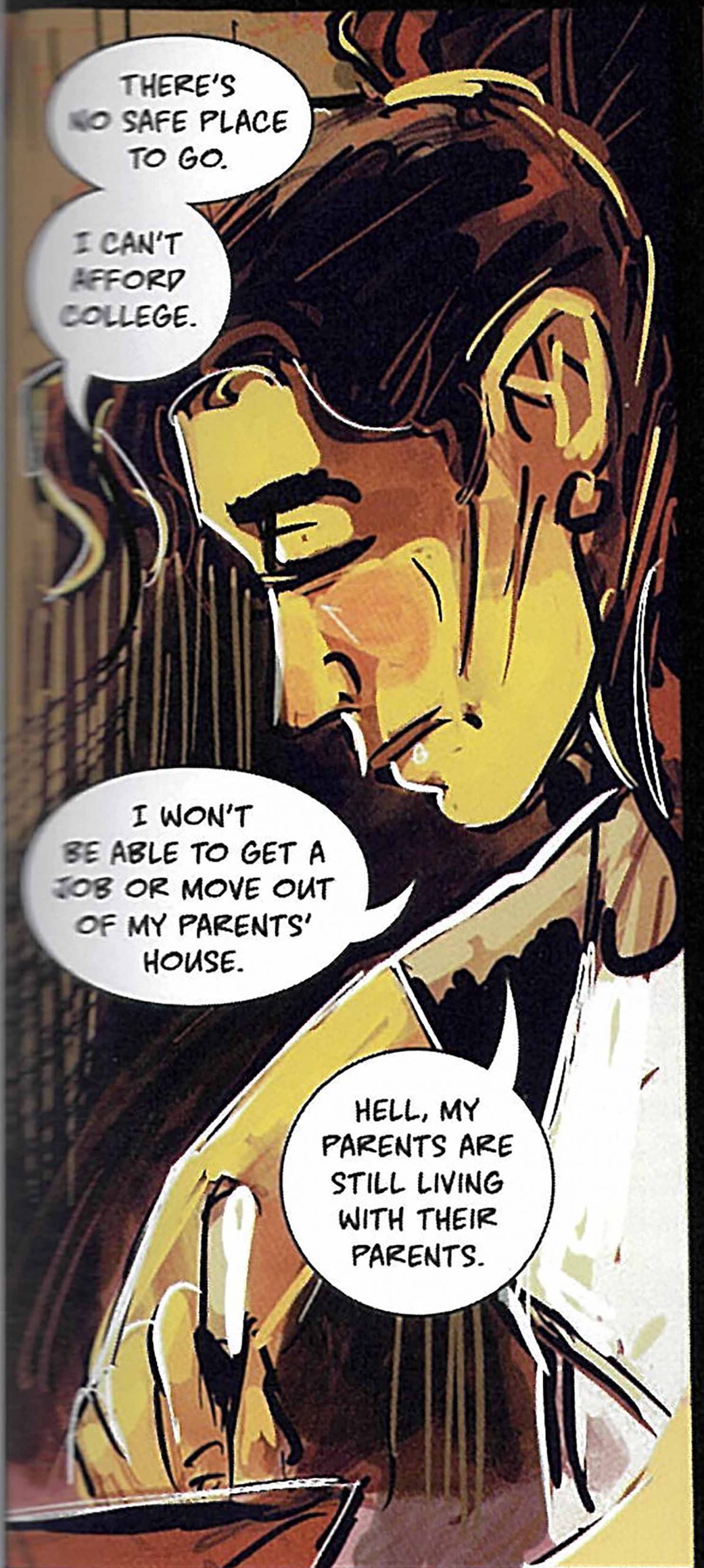

And here, her best friend Joanne narrates a lament that might resonate with recent high school graduates:

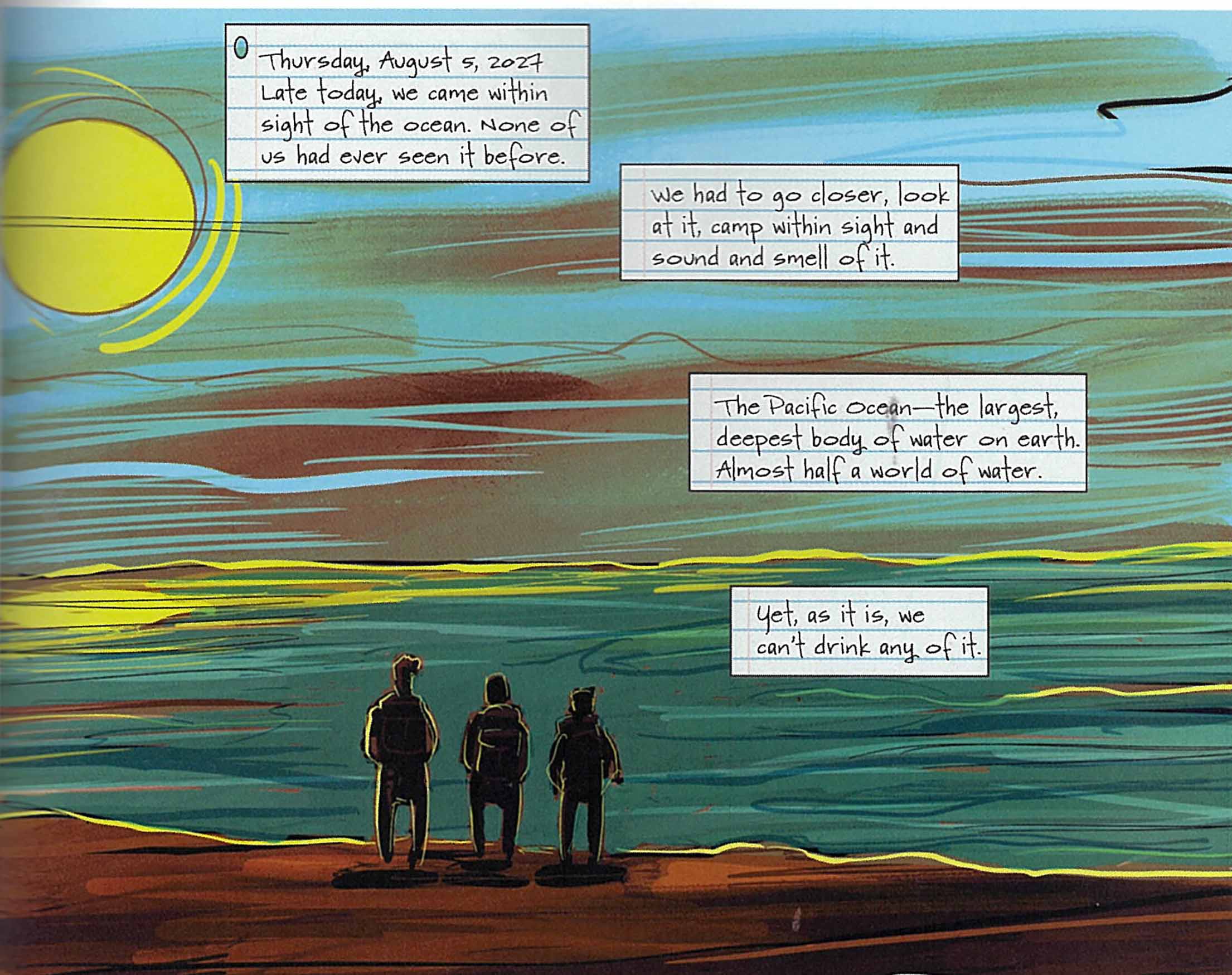

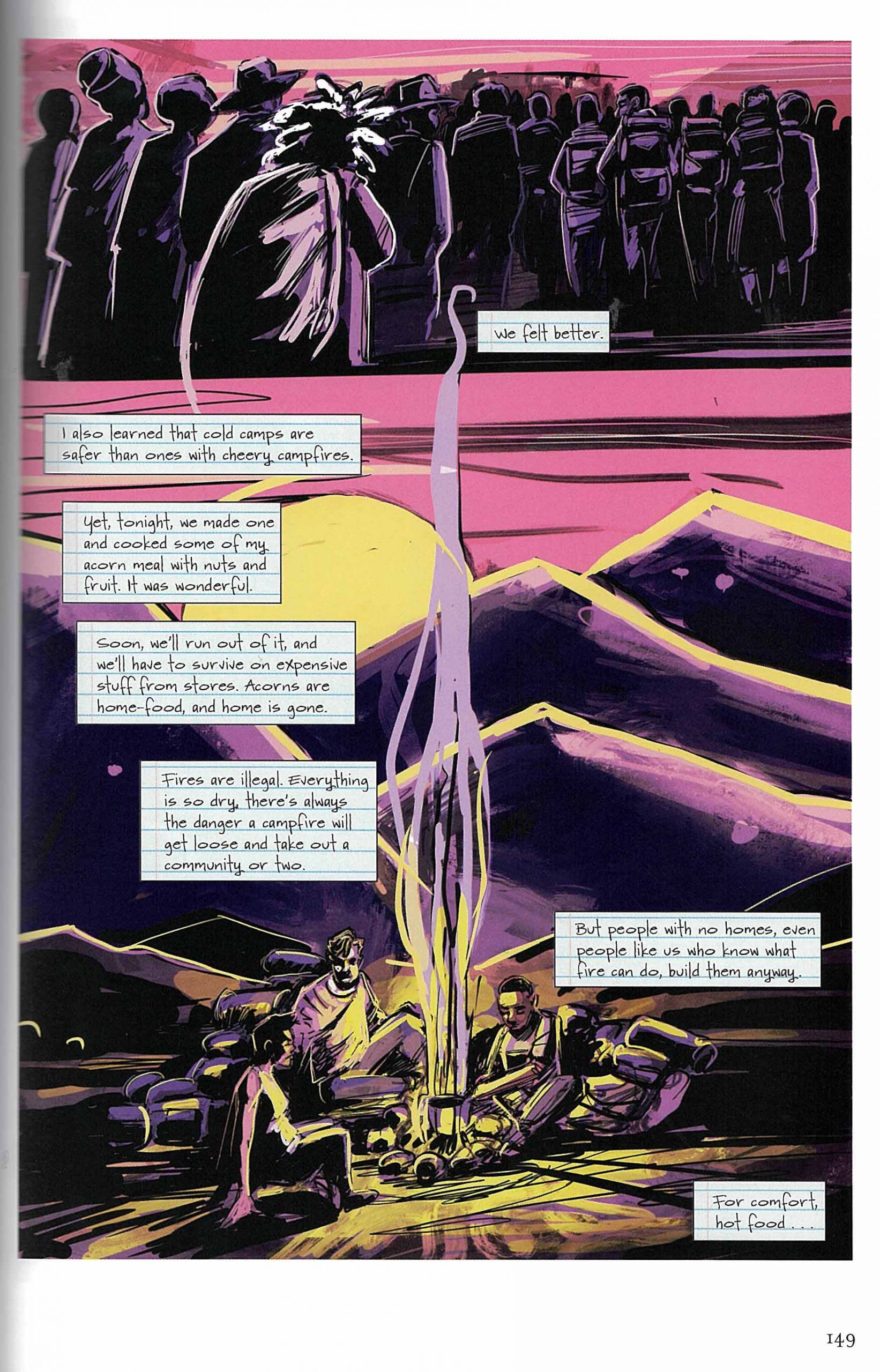

As you can tell from the images so far, Jennings’s artistic vision is not only striking, but rich with color: he thanks no fewer than seven “color production artists” in the book’s acknowledgements. The above image in particular showcases Jennings’s graduate training in woodcuts, especially the influence of the early twentieth century Belgian artist, storyteller, and seminal comics precursor Frans Masereel. As Jennings explained to Frederick Aldama in a February 2020 interview, “I love printmaking, but I don’t have time to cut prints. But I can simulate that feel through the digital, and that’s something that I try to do.”

While Jennings’s stunning artwork attracts readers to this book, Damian Duffy’s role in its success shouldn’t be underestimated. (For more on Duffy and Jennings’s work, see my 2015 review of “Kid Code” from the groundbreaking DC publishing company Rosarium.) Distilling a 300-page story to a manageable comic that retains the nuance and complication of the original is no easy feat. Duffy’s choice of visuals conveys Butler’s expertise in rationing out small, shocking details that parcel out the depth of the story’s dystopian horror. I won’t share too many, so as not to spoil the plot, but readers gradually learn, for example, of the family’s reluctance to call the police or fire departments because they can’t afford their fees.

This image appears early in the book, demonstrating not only Butler’s brilliance, but the broader brilliance and purpose of the best science fiction:

A handgun in space? Do guns even fire in space? Olamina dreamed this image after hearing from the news about an astronaut abandoned in space, then from her parents about a neighbor who committed suicide, then she recorded the dream in her journal. This type of “Wait, what?” visual illustrates (literally!) what science fiction does best, jolting our thinking beyond the boundaries of the present and the possible.

Duffy and Jennings aren’t the only ones to see the relevance of this book for our difficult and complicated present. An opera adaptation by singer-songwriter Toshi Reagon and her mother Bernice Johnson Reagon (the latter of Sweet Honey in the Rock fame) has just been making the rounds of shelter-in-place live streams, and was the last in-person performance at UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance before the pandemic closed the stage. “Octavia made it very clear in her predicting,” Toshi Reagon said in a recent interview for “The Root,” it would be “our disinterest with our civic duties that’d move very lame people into powerful positions, and with those powerful positions they’d take up a lot of resources and a lot of space.”

Fortunately, Abrams Comic Arts is making space for Jennings to put more works like this into circulation, and into the public discourse. Jennings now runs Megascope, a new Abrams imprint “showcasing speculative works by and about people of color” as explained on the back flap of “Sower.” Such projects open up space for the type of creative, productive vision that we’re going to need not only to fix the mess we’re in but to survive—and beautifully so, as in this one final image I’ll leave you with: