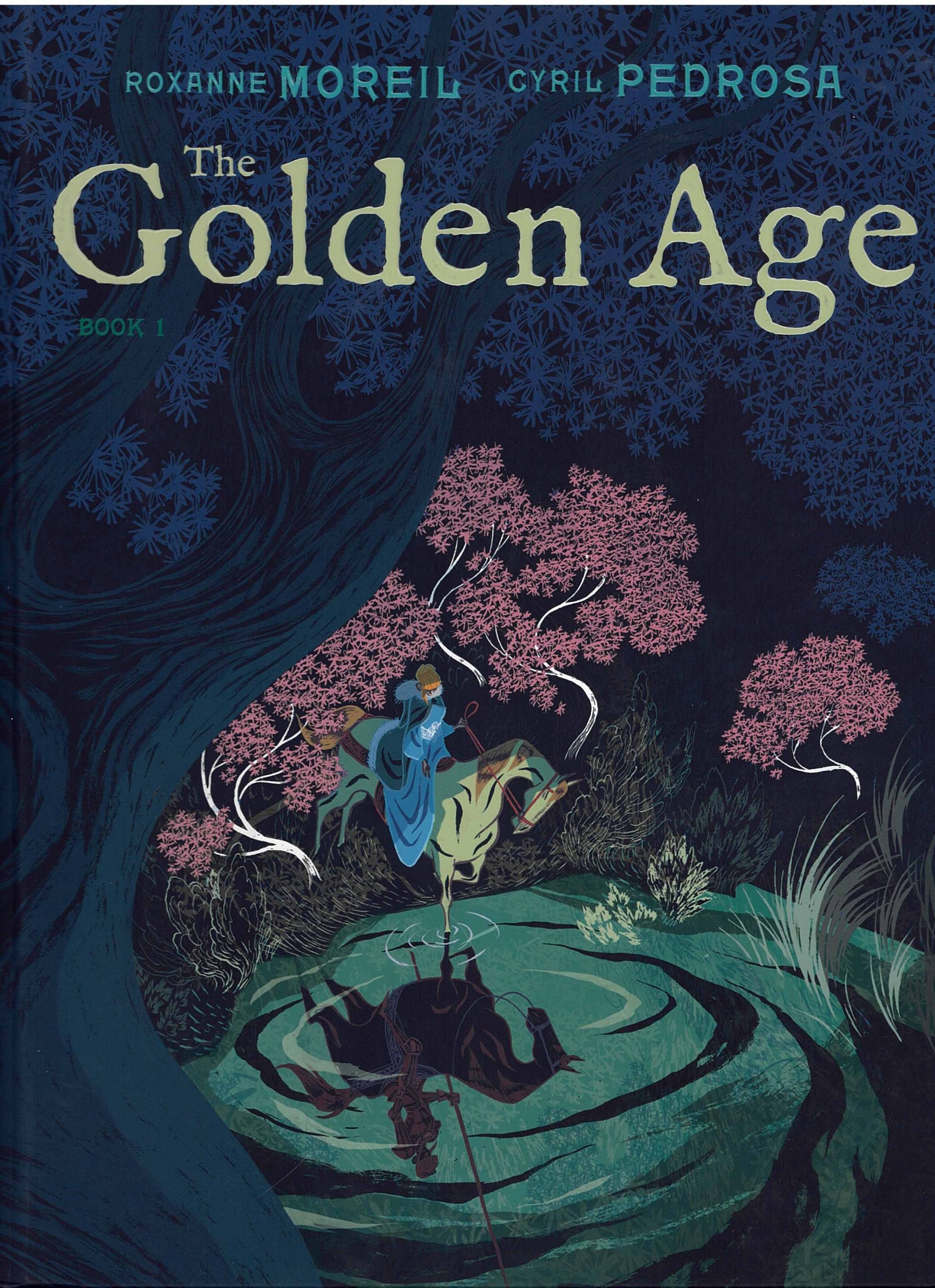

“The Golden Age: Book One.” By Roxanne Moreil and Cyril Pedrosa. Trans. from the French by Montana Kane. (Originally published 2018.) First Second, February 2020. 224 pp. Hardcover, $29.99. 14 and up.

Thanks to Fables Books, 215 South Main Street in downtown Goshen, Indiana, for providing Commons Comics with books to review.

COVID-19 PROTOCOL: Please wear a mask as required by local mandate, and follow store guidelines. You may enter at either the front or back entrances. High risk customers can still make browsing appointments before or after hours, and all customers can continue to order online at fablesbooks.com, over the phone 574-534-1984, or via email fablesbooks@gmail.com. *Order deadline to ensure Christmas delivery: December 15.*

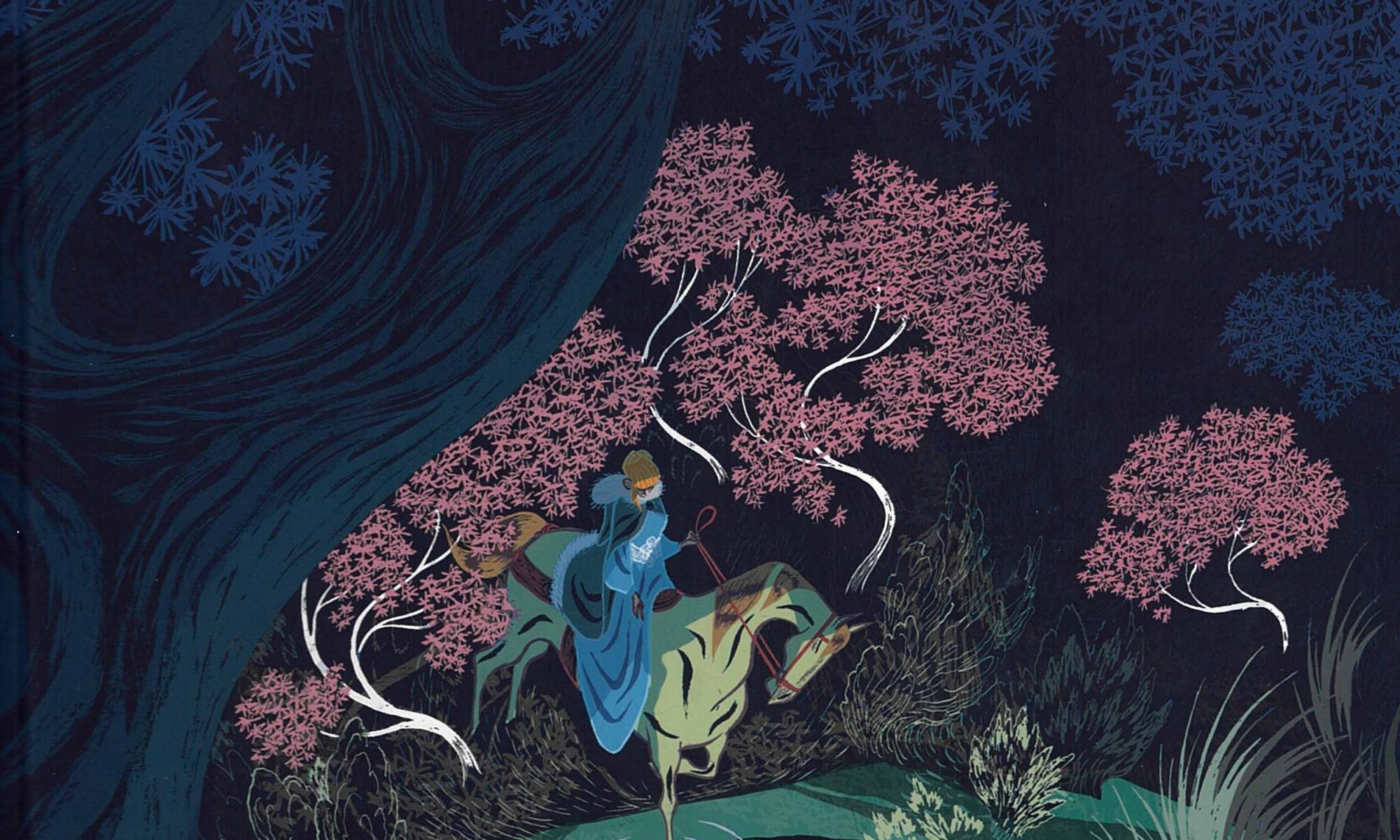

Right from the opening pages of “Golden Age,” French artist Cyril Pedrosa catapults readers into his surreal, color-lush medieval-era landscape:

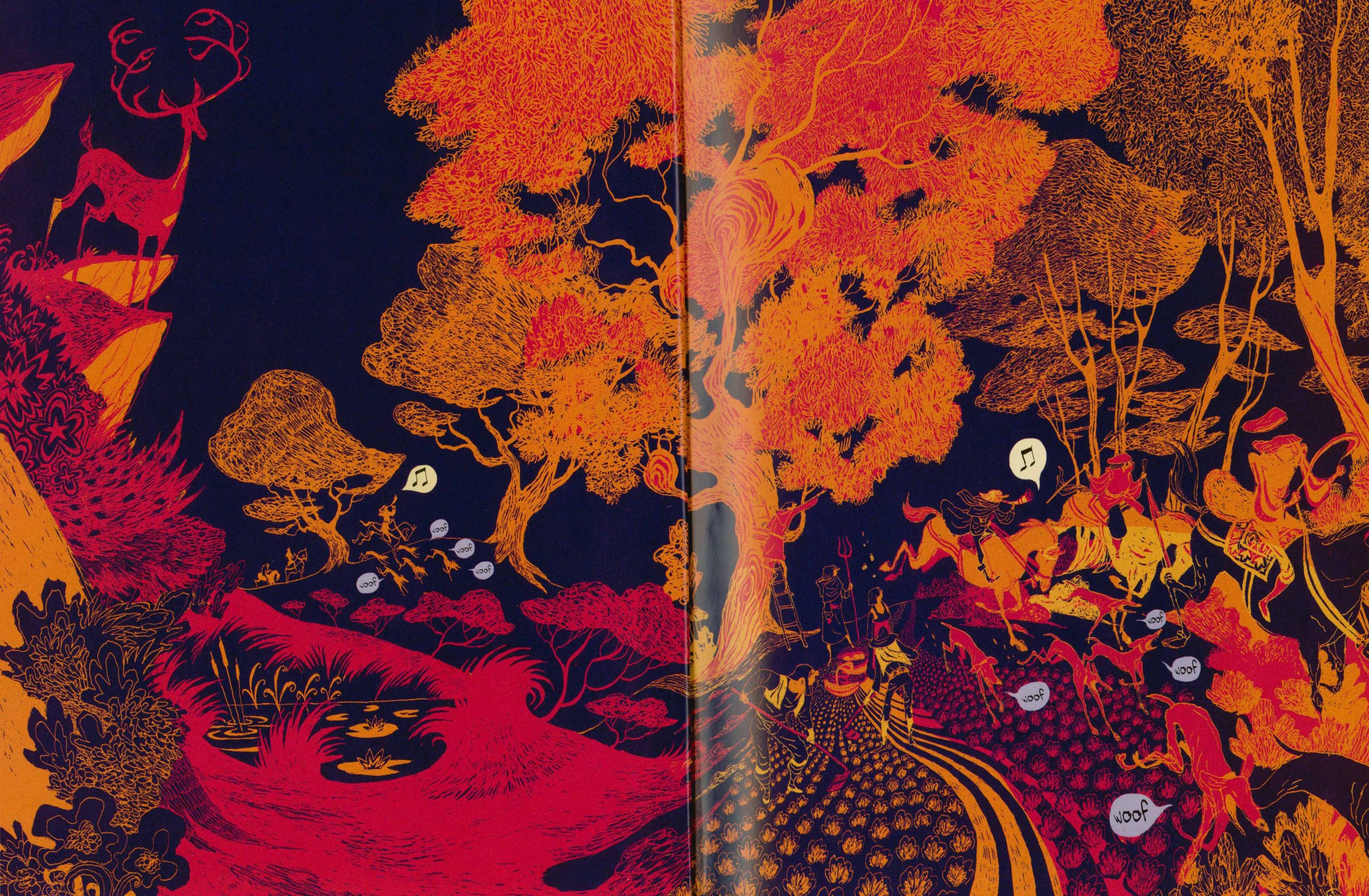

Co-writer Roxanne Moreil doesn’t waste time either, swirling the class divide central to this story immediately into the visual soup. The peasants pause their work to watch the nobles and their dogs trample their crops for the sake of royal recreation. Trouble bubbles up from the very soil of the kingdom of Antrevers.

Moreil and Pedrosa developed their story for a full year before committing it to paper, and their hard work pays off: the complex characters and scenarios make “Golden Age” exceedingly difficult to put down. The world of the royals in the story holds villains, heroes, heroines, and all kinds of figures who rest somewhere in between, as this gorgeous and dizzying court scene sets up toward the start of the book:

The two main protagonists shown here are Tankred and Bertil, old friends of Princess Tilda, arrived after a long absence to support Tilda’s upcoming coronation to become queen. Her father, the king, has just died, and he made his wishes clear: Tilda, not her brother, should succeed him. Tilda has plans to improve conditions in the kingdom, where peasant life is difficult and too heavily taxed. Malevolent figures in the court, however, would rather not see Tilda take over as queen and make changes to the status quo. Her brother is much younger, and much easier to manipulate, so a coup is staged to install him as king, rather than Tilda. Good thing Tankred and Bertil are there: the three of them escape together, hoping to beat the unscrupulous Lord Vaudémont (pop culture cousin to Voldemort?) to the kingdom of a longtime ally of Tilda’s father.

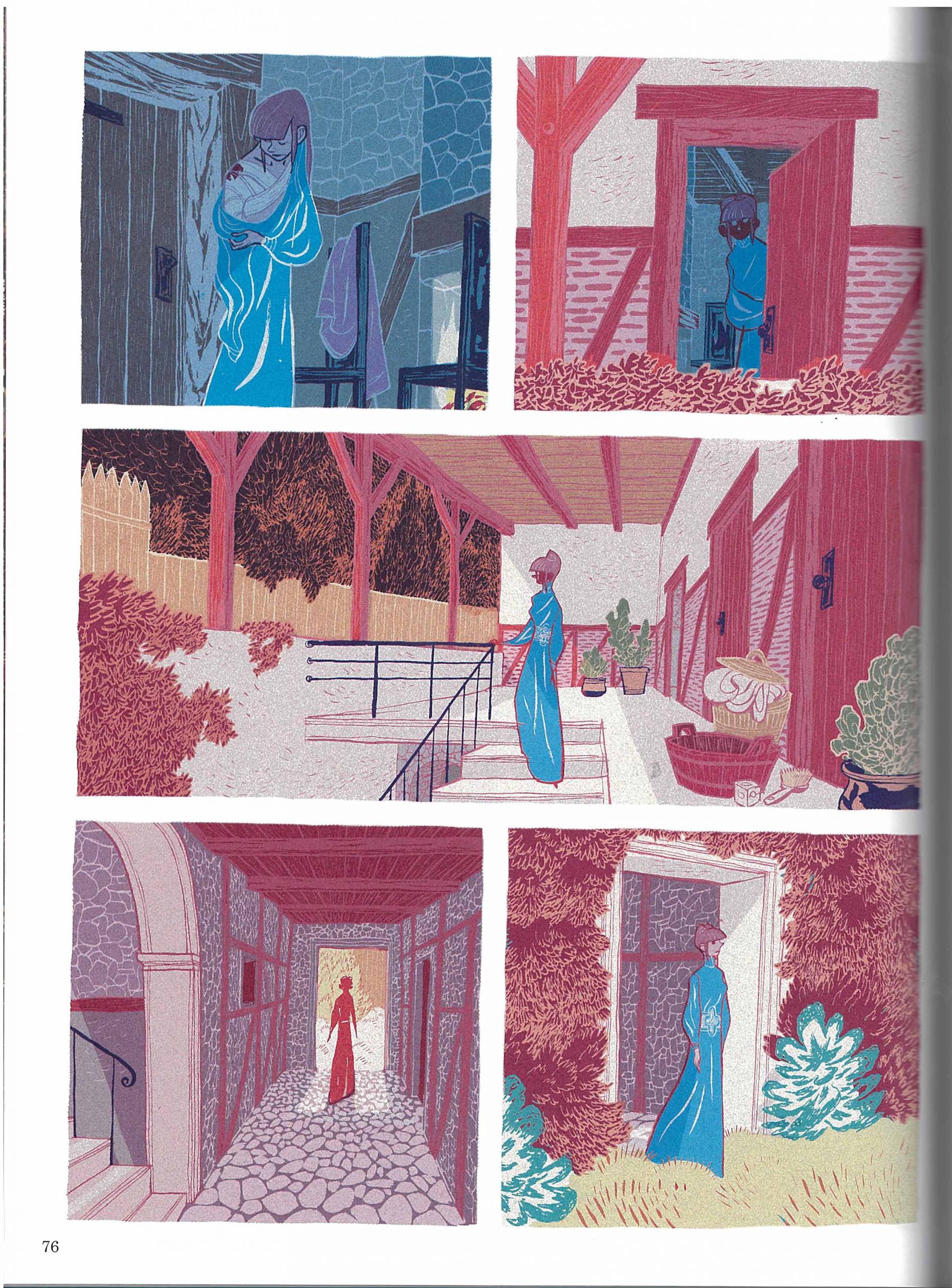

“Golden Age” wears its fairy-tale roots on its ornately decorated sleeve, but doesn’t dwell within the most tired tropes of these stories. Familiar plot twists instead serve as groundwork that gives readers enough mental space to slow down and appreciate Pedrosa’s breathtaking art. Pedrosa borrows not just settings, but also artistic techniques from medieval era paintings, tapestries, and illuminated manuscripts. Much as in medieval paintings, especially, visually flat characters are layered over similarly flat but intricately patterned worlds. The result is that the characters look as if they could slide right off the page, but instead magically float their way, ethereal, through their scenes. (For a more craft-expert analysis of Pedrosa’s technique, click on this review.) In the court image above, for example, check out the floor, Tankred’s robe, and the wallpaper, as well as the silhouettes that fill the windows.

Pedrosa didn’t just click a button on Photoshop and pop the color to create these effects. This level of detail takes hours and hours of work. “The secret is not to sleep,” Pedrosa confessed in a video interview for Europe Books. Whatever book he’s working on, “I think about it all the time,” he says. This might explain how he creates such a powerful sense of immersion for his readers as well.

Pedrosa’s flat composition, combined with intense color saturation, sucks readers in to a whirlpool of color and pattern—which, although often lacking the panels that usually serve to create movement in comics, makes the book feel as if it’s animated. Pedrosa has, in fact, worked on Disney films—“Hercules” especially echoes throughout this book—as did Kay Nielsen, an old-school fairy tale illustrator who Pedrosa’s work first reminded me of. Nielsen’s career, however, traveled in the opposite direction as Pedrosa’s: instead of moving, like Pedrosa, from Disney into more independent work, Nielsen, born in Denmark, developed his illustration career in England in the early 20th century, then traveled to Hollywood later in his life to work, most notably, on Disney’s “Fantasia.” Nielsen’s work, in an echo of the book’s title, flourished in, then helped close out, what’s now referred to as the “golden age” of illustration.

Pedrosa’s and Nielsen’s styles differ in many respects—not the least of which is that Nielsen illustrated entirely by hand, whereas Pedrosa openly discusses the ways technology enhances his art. Both, however, visually envelop their readers to an extent matched by only a handful of artists:

With that level of detail largely inaccessible to a working twenty-first century artist, Pedrosa harnesses the narrative power of comics to achieve a similar level of immersion:

Pedrosa has also mentioned the seminal sixteenth-century Netherlandish painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder as an influence. Bruegel’s paintings are so dark-hued compared to Pedrosa’s color explosion, that this reference is less visible on first glance. The connection begins to make sense, however, if you consider the depth of Bruegel’s sweeping scenes, especially the way he managed to make each individual within his scenes distinct:

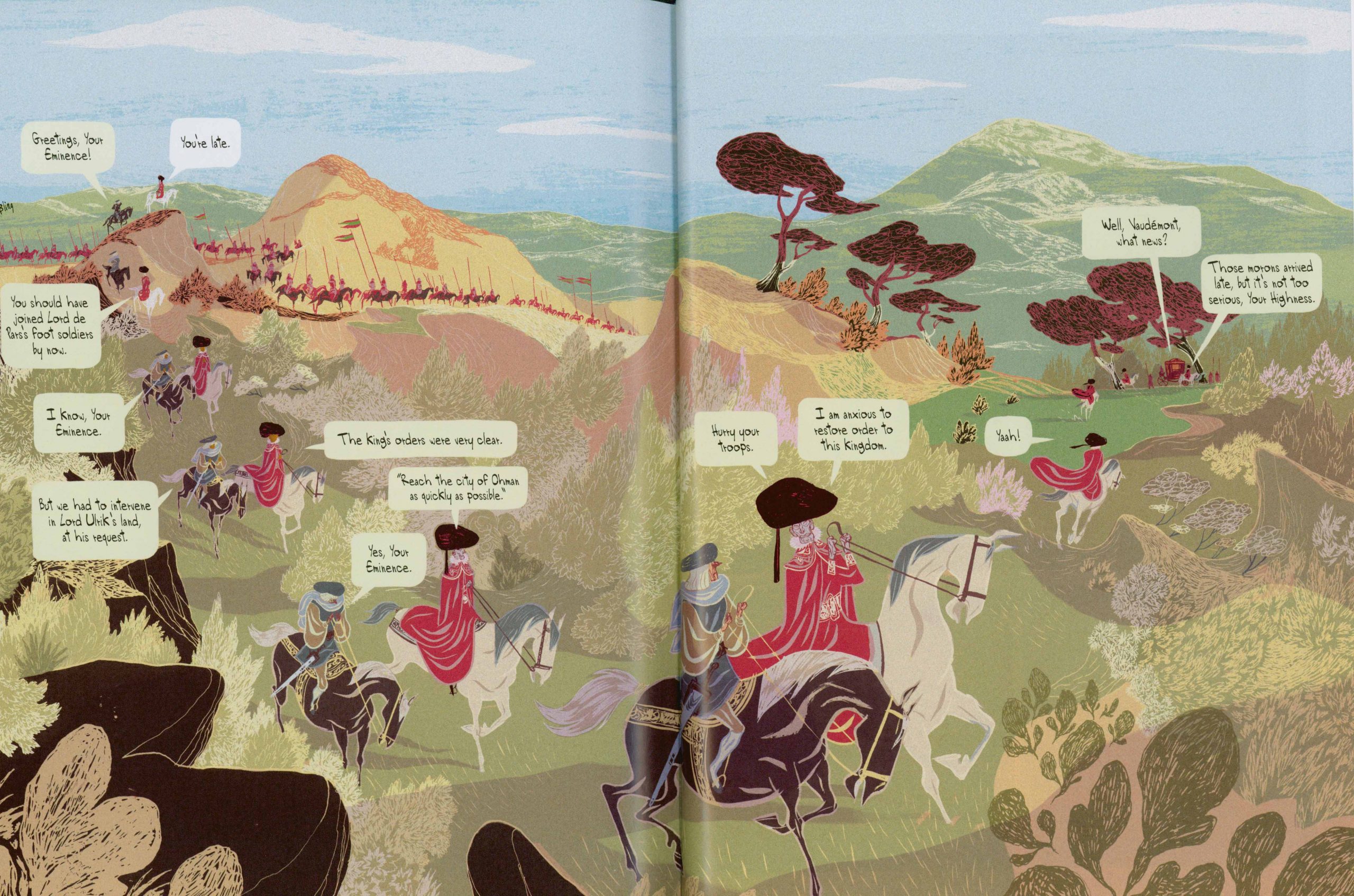

Pedrosa echoes the sweep of Bruegel’s work, but again adapts the language of comics to maintain energy in the scene, and move Lord Vaudémont across the two-page landscape:

Try to give yourself one sitting for this book, because you won’t want to put it down. “We had two desires,” said Moreil in the Europe Comics video, “to write a political tale, and especially to write a real comic adventure that we would ourselves like to read.”

Most fans in the U.S. will need to stop at the end of Book One, however: the English translation of Book Two isn’t due out until Fall 2021—although if you you’re impatient and can make your way through the French, you can find the original version online.

This is the type of book it’s worth shelling out the cash to buy in hardcover for yourself or for a very lucky person as a holiday gift. Please resist the click, especially when it comes to books: ordering from your local bookstore is really easy, genuinely friendly (as opposed to those creepy, featureless smiling mouths on the Amazon boxes), and will keep them open and contributing to a healthy downtown. (Remember Goshen folks, Fables orders need to be in by December 15th to arrive in time for Christmas.)

I leave you with a video of Pedrosa demonstrating his illustration technique for France Inter, the French version of public broadcasting. You don’t need to understand French to be as enchanted by this video as you will be by this brilliant and beautiful book.