“Tunnels.” Written and illustrated by Rutu Modan. Translated from the Hebrew by Ishai Mishory. Drawn and Quarterly, $29.95. November 2021. 284 pp. Teen to adult (but my 9 and 12 year olds loved it).

Disclosure: I received a free review copy of this book from Drawn and Quarterly.

Thanks to Fables Books, 215 South Main Street in downtown Goshen, Indiana, for providing Commons Comics with books to review.

Check Fables out online at www.fablesbooks.com, order over the phone at 574-534-1984, or email at fablesbooks@gmail.com.

“[W]e are all stuck here in this small piece of land,” said comics artist Rutu Modan in a recent CBC interview, when asked about the fraught location of her home country Israel. “Basically, we have the same target. I believe that most of the people living here want to live happily ever after. But the interpretation of the way to go there, to get to this perfect future, the ways are really different.”

Modan has never been one to shy away from difficult questions, but she doesn’t take herself too seriously, either—keep an eye out for a cow jumping over the moon in her most recent book, “Tunnels.” The romance and intrigue that Modan works into all of her comics (such as “The Property“) are never merely superficial plot devices, but a means to delve deeper. Modan’s newest story tunnels its own elliptical, surprising, and delightful narrative path as readers follow her rich, complex characters around and within their difficult, contested setting.

The characters in “Tunnels” demonstrate exceptional depth as well as tunnel vision. All are in search of the Ark of the Covenant, but for different reasons. The plot echoes William Faulkner’s classic “As I Lay Dying,” but with a goal to exhume rather than bury. Each character’s individual desires cloud what should be the shared purpose of finding one of the most significant cultural artifacts of world religious history. Instead, the hazards of competitive tunneling threaten to bury the entire cast.

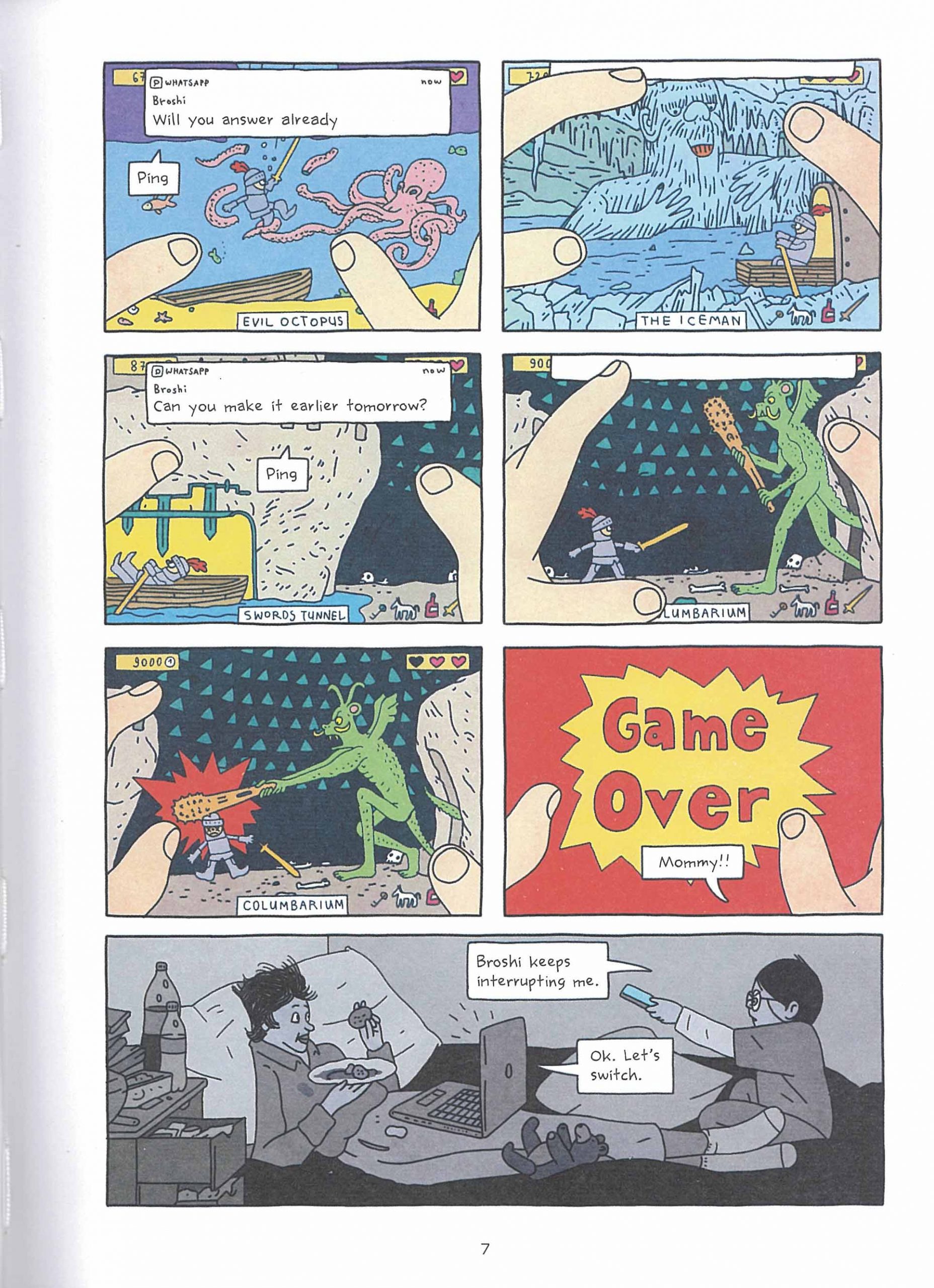

The story opens directly into a video game on an iPhone. Two thumbs on the edge of the screen guide a knight battling monsters at sea and on land (and yes, in tunnels), while a caller keeps trying to interrupt the game. Readers don’t know whose hands hold the phone, or who this “Broshi” is who keeps calling and texting and breaking into the game.

When the game ends and the camera zooms out, readers are allowed to see the story’s protagonists: Doctor, the kid playing the game, and Nili, his mom. In contrast to the colorful, active world of the game, the panel that shows their surroundings reveals the two charcters’ entombment in a gray, cluttered room:

If the real world looks this drab—not only flat and gray, but buried at the bottom of the page, weighed down by the preceding panels—no wonder Doctor spends most of the story seeking out electronic devices and draining their batteries. As the perspective continues to pan back, however, readers witness these two characters’ surroundings, stuffed with all manner of consumer riches. Nili doesn’t look unlike J.R.R. Tolkien’s dragon Smaug atop his hoard. As the story will begin to subtly suggest, perhaps the pair’s real world is richer than either of them is able to see. “[I]f only more of us found the present adequate,” Modan writes in her afterword, “instead of squabbling over the past.”

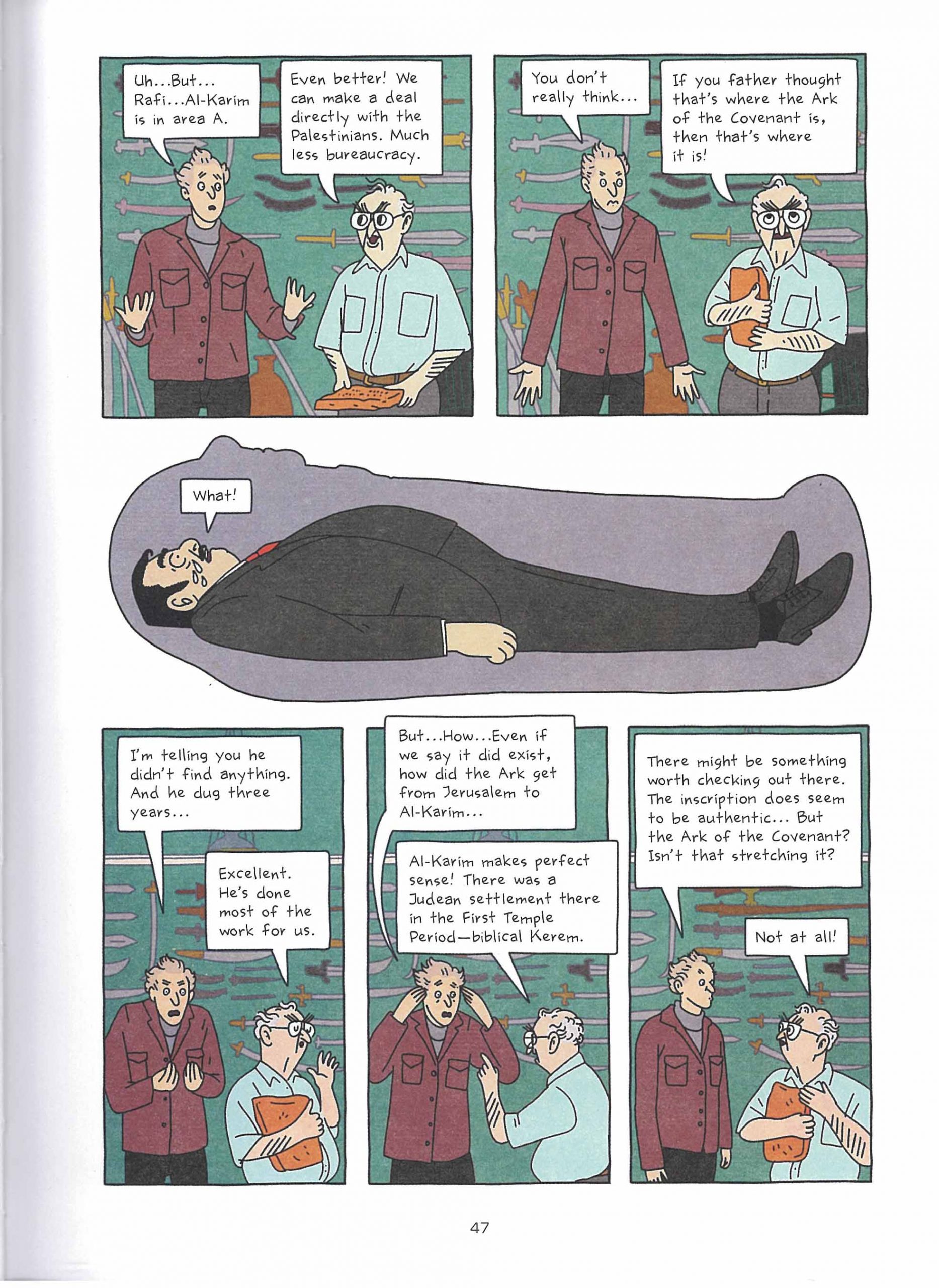

Nili and Doctor aren’t the only characters who willingly entomb themselves. Emil Abuloff—a sketchy, rapacious, but not unkind antiquities dealer—crawls into one of his own holdings to listen in on a private conversation between Nili’s brother Broshi, an archaeology professor desperate for tenure, and his scruple-free academic mentor Rafi, who has a long history with Nili and Broshi’s family: he pushed their ailing father Israel out of academia, then spent the rest of his career claiming Israel’s research as his own.

Family betrayal and treasure-hunting aside, what this page really makes clear is how Modan’s mastery of the format is driven not just by her narrative, but by her expert page composition. Many have compared her distilled visual style to Belgian comics master Herge’s ligne claire. As she explained to the literary magazine “Solrad,” however, “Herge could draw pages packed with tiny panels with tons of activity and action, but you never get lost in these pages. Ligne claire to me is not about the line but about the clarity of the storytelling.”

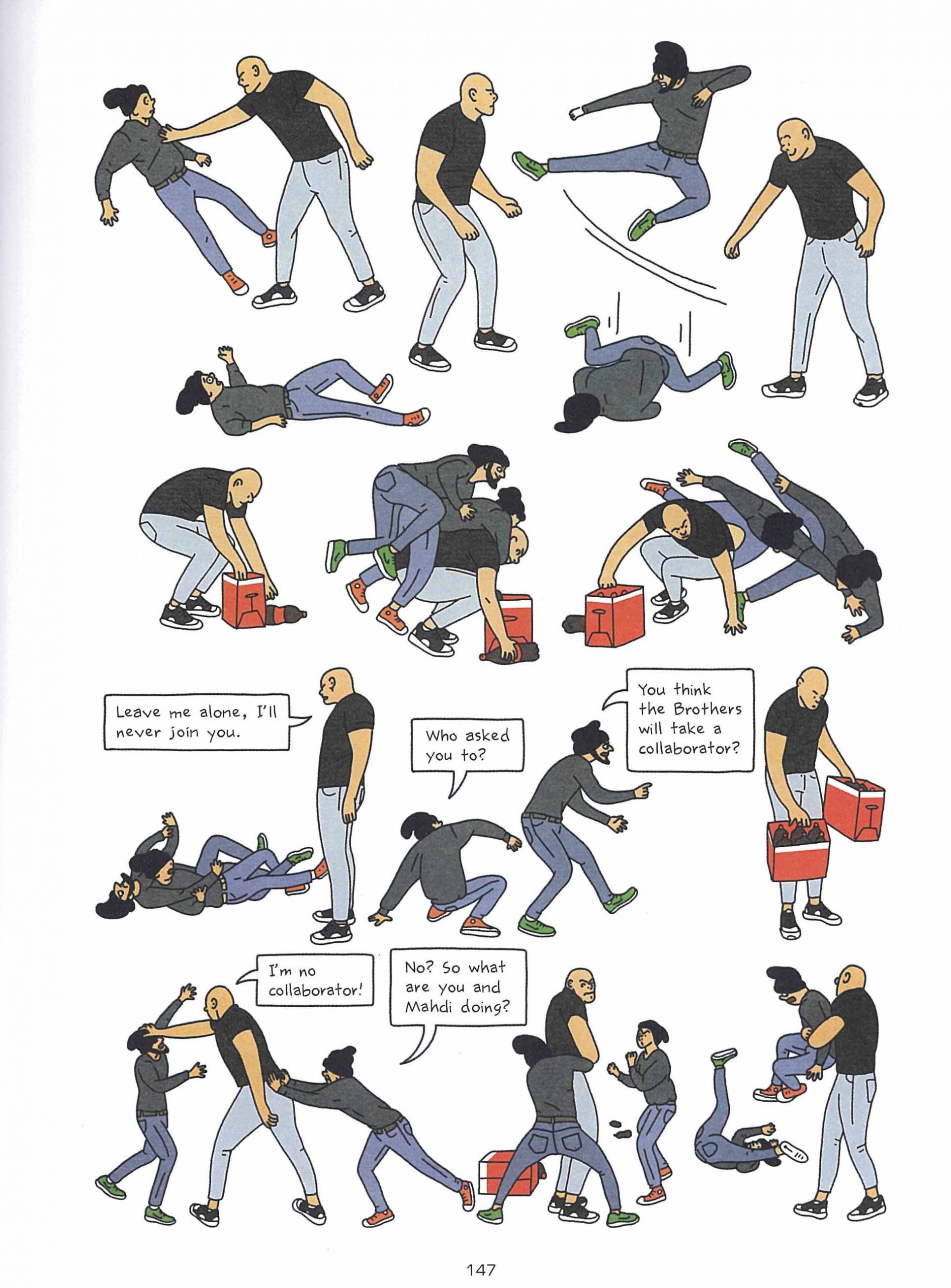

Although Modan’s visuals are smoothed out and simplified, her characters are anything but, especially because of Modan’s unique methods for developing her comics. Plenty of comics artists use photo references for their illustrations, or have friends pose for them so they can figure out how to draw certain types of people and bodies in motion. Modan, however, auditions and hires an entire cast of actors—all credited in a cast list at the back of the book—to work through scenes from her storyboard draft. She watches them act out the scenes, takes photos, and then revises the story and illustrations after observing the actors’ movement, dialogue, interactions, and improvisation. This process can, at times, change the entire dynamic of a scene, as it did between these three characters:

As Modan explained to “Solrad,” the actors challenged, and eventually revised, her vision of the scene. That beefy character being attacked above, one of two Palestinian brothers digging in the same tunnels as Nili and her crew? Modan initially pictured him as small and vulnerable. When Modan auditioned that role, the actor “was sitting down and he had a great face,” so she had no idea that he didn’t fit her initial impression of the character. “When he came in the day of the shoot I finally saw him – two meters tall, broad shoulders. Turns out he’s a champion heavyweight boxer.” Rather than fire the actor, however, Modan’s open and inquisitive nature was curious how the scene would play out. “The change of sizes changed how I understood that scene; now it’s not two strong people picking on a weaker person, but one strong against a weak pair – which has a lot more dramatic potential.”

The main reason why all of Modan’s characters demonstrate “dramatic potential,” however, is that Modan isn’t afraid to show flaws and complications, even in her heroes. No one in this story is perfect, or even perfectly evil—although the prune-faced and grasping academic Rafi comes close. Modan works like a novelist, placing these realistic characters—not just their actors—into complicated situations to observe what they do as she writes. It makes her stories unpredictable and exciting, without being structurally manipulative. Even the clearly unlikeable characters, like Rafi—whose career is built on theft—ends up in surprising places the end of the book.

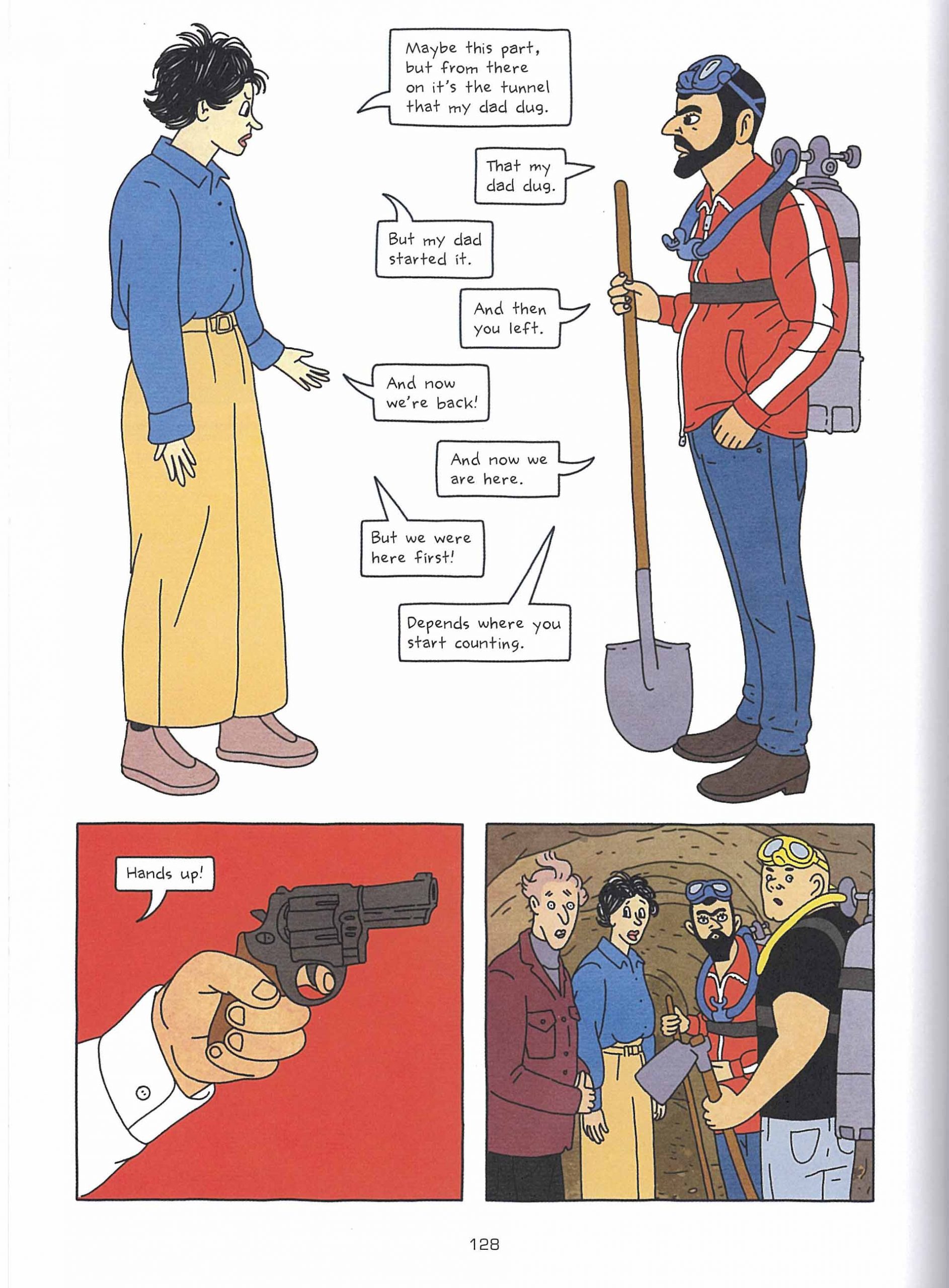

“It took me ages to figure out how I can present this thing,” meaning the Israel/Palestine conflict, “not to make it into a ‘good vs. evil’ thing, but show the situation with the complexity I see in it,” she explained to “Solrad.” Throughout all of her work, Modan conveys complexity not through over-explanation but through distillation. In the image below, for example, Nili and her crew encounter Mahdi, an old Palestinian friend, as they tunnel for the Ark. Mahdi and Nili met as kids, accompanying their fathers on digs. Their argument in the image below is ostensibly about who has the right to continue digging in the already existing tunnels. Step back from the conversation, however, and they could be talking about the age-old history and conflict that surrounds them:

As Modan writes in the book’s afterword, Israel isn’t the only place in the world right now that could use a dose of honesty. She notes how the pandemic has laid bare the ways that powerful people can twist numbers and statistics to serve their own purposes. “In this confusing state of affairs, when each fact is immediately contrasted with a counter-fact and everyone is branded a liar, when the word truth can be used only in apology and within quotation marks, it seems that the only object that can claim total honesty is fiction itself.”

Modan’s statement might sound a bit cavalier until you hear her refer to the Bible as a work of honest fiction as well, a concatenation of made-up stories pulled from and humming with truth.

Modan might get flak for that statement—and probably already has. But she herself does her best to speak from a position of honesty, unafraid to explore her own contradictions and complications. “I have racism in me,” she explained to the Jewish Book Council. “I try not to have this racism or prejudice. But I wanted to also look at this in me, in myself. And this is the nice thing about writing fiction.” By showing her fictional characters expressing the prejudices she grew up with and still lives within and around, it helps her say to her readers, as she phrases it, “let’s look at it, let’s face it.”