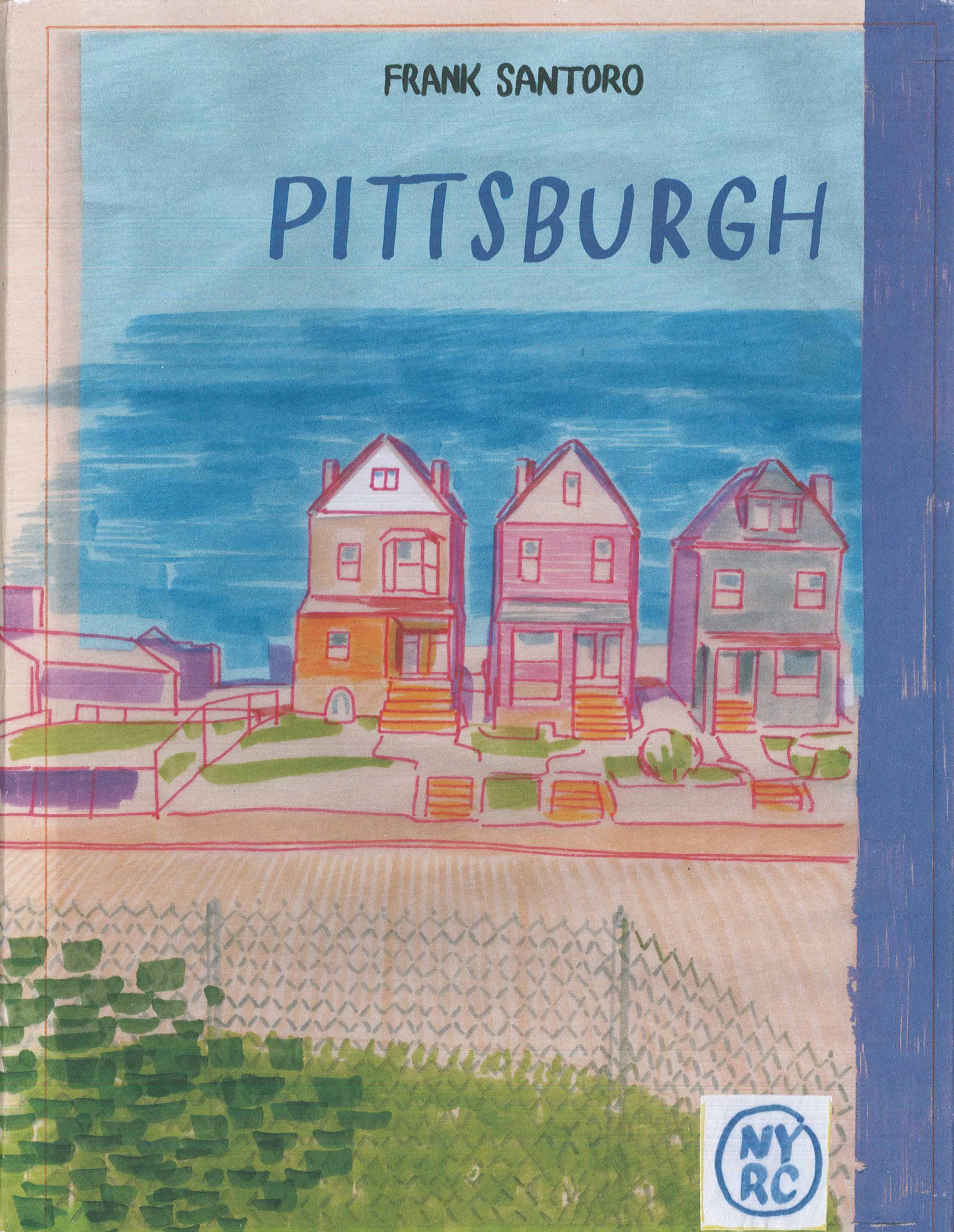

“Pittsburgh” by Frank Santoro. New York Review Comics, September 2019. 216 pp. Hardcover, $29.95. Adult.

Thanks to Fables Books, 215 South Main Street in downtown Goshen, Indiana, for providing Commons Comics with books to review. Visit the store or contact them at fablesbooks@gmail.com to find or order this or any book reviewed on this blog.

If you’re in the Michiana area looking for a last-minute holiday gift, Fables books has got your back! They’ll be open Monday 12/23 and Christmas Eve.

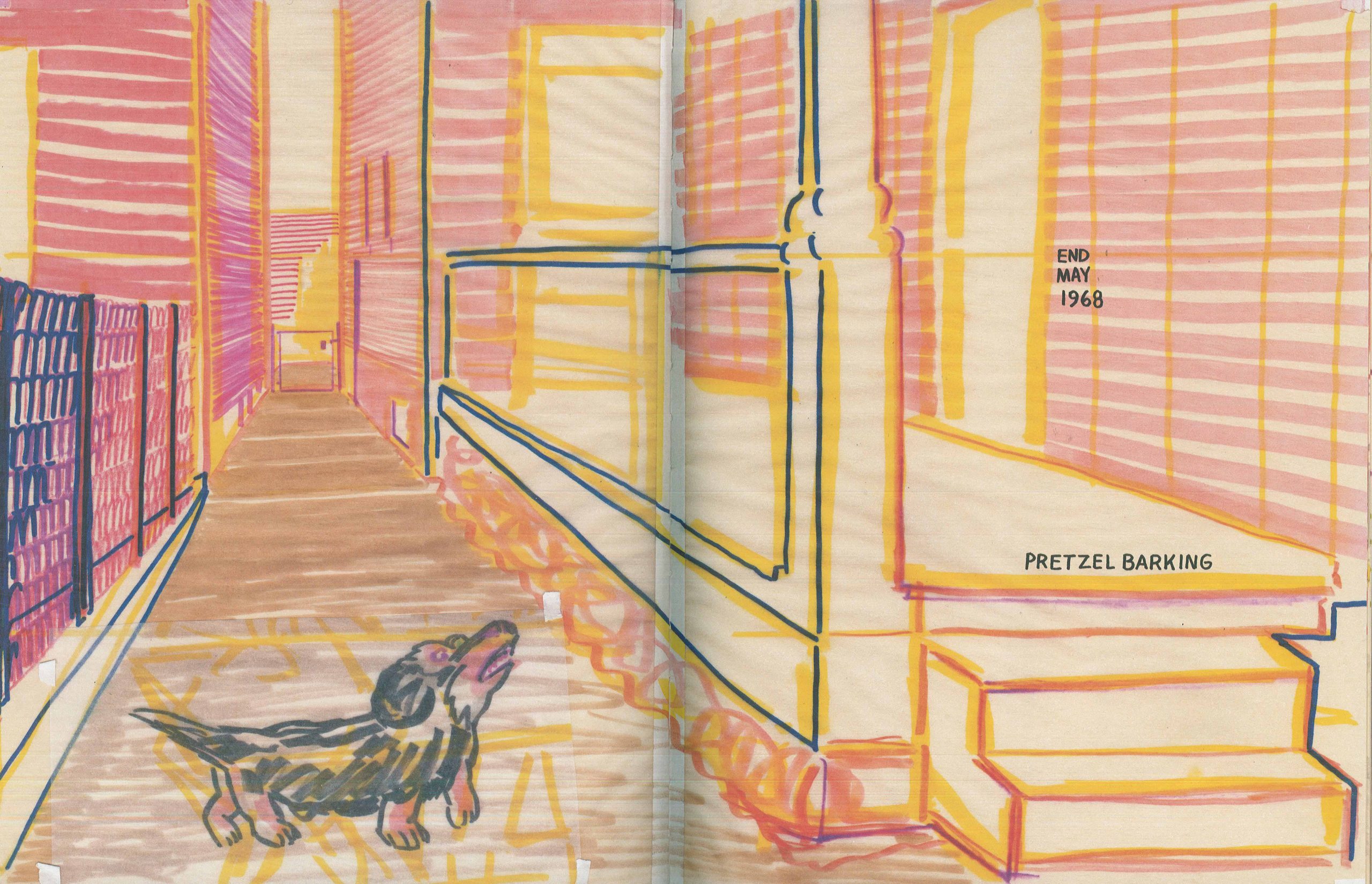

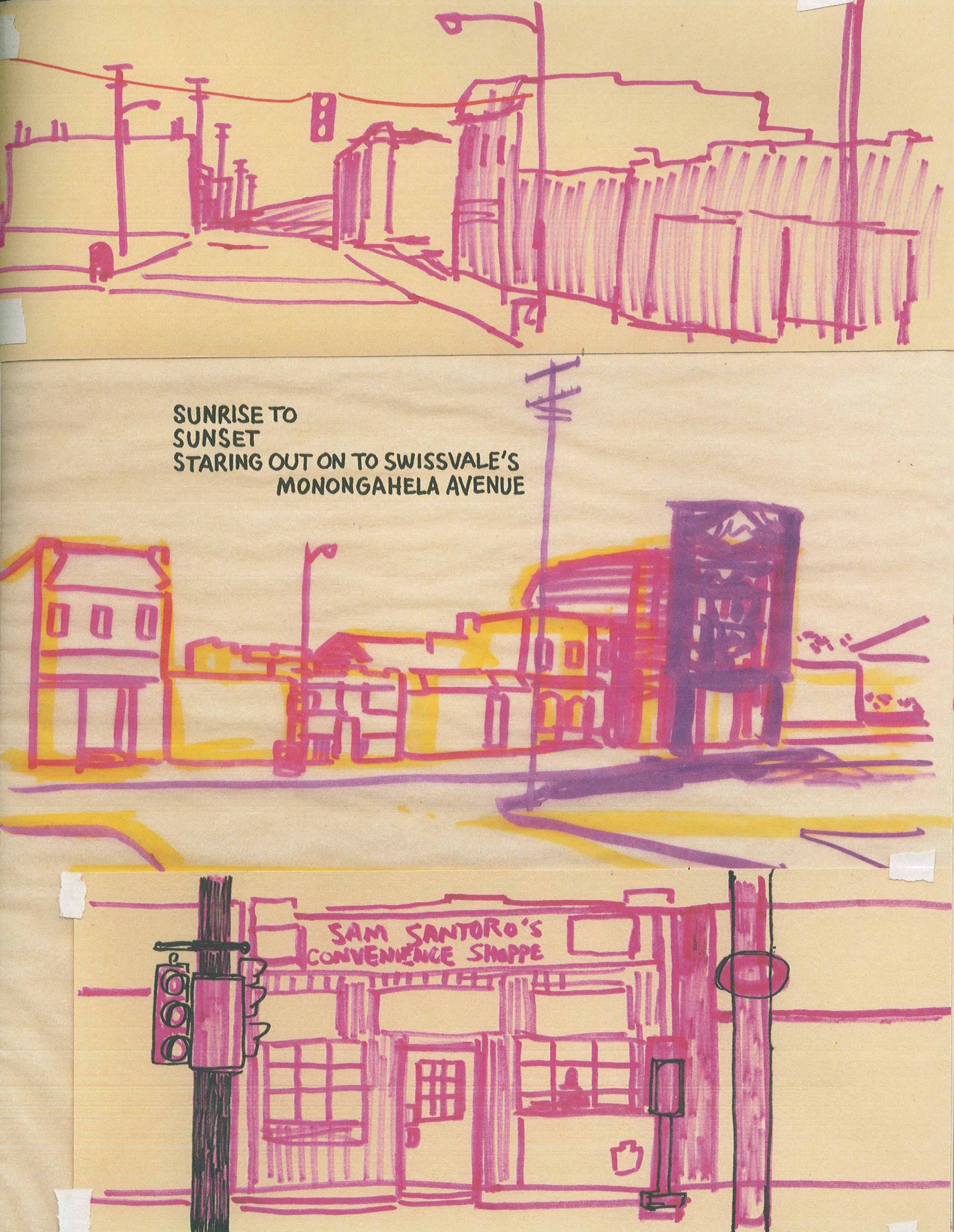

Think Pittsburgh—what do you picture? Most people imagine heavy, decaying industry: steel, rust, and grime. Frank Santoro sees color—really bright color. Witness this two-page spread:

In his new book “Pittsburgh,” Santoro, a native of the city, graciously invites readers into his personal history of the place, as he works to summon and piece together memories of his family, neighbors, and neighborhoods.

In a quick flip through “Pittsburgh,” a reader’s critical mind might kick in: this is messy! Look, he doesn’t even cut and paste to disguise the edges of what’s been added and removed—he cuts and tapes with white rather than clear tape (check out the white tape around the corners of Pretzel the dog in the image above).

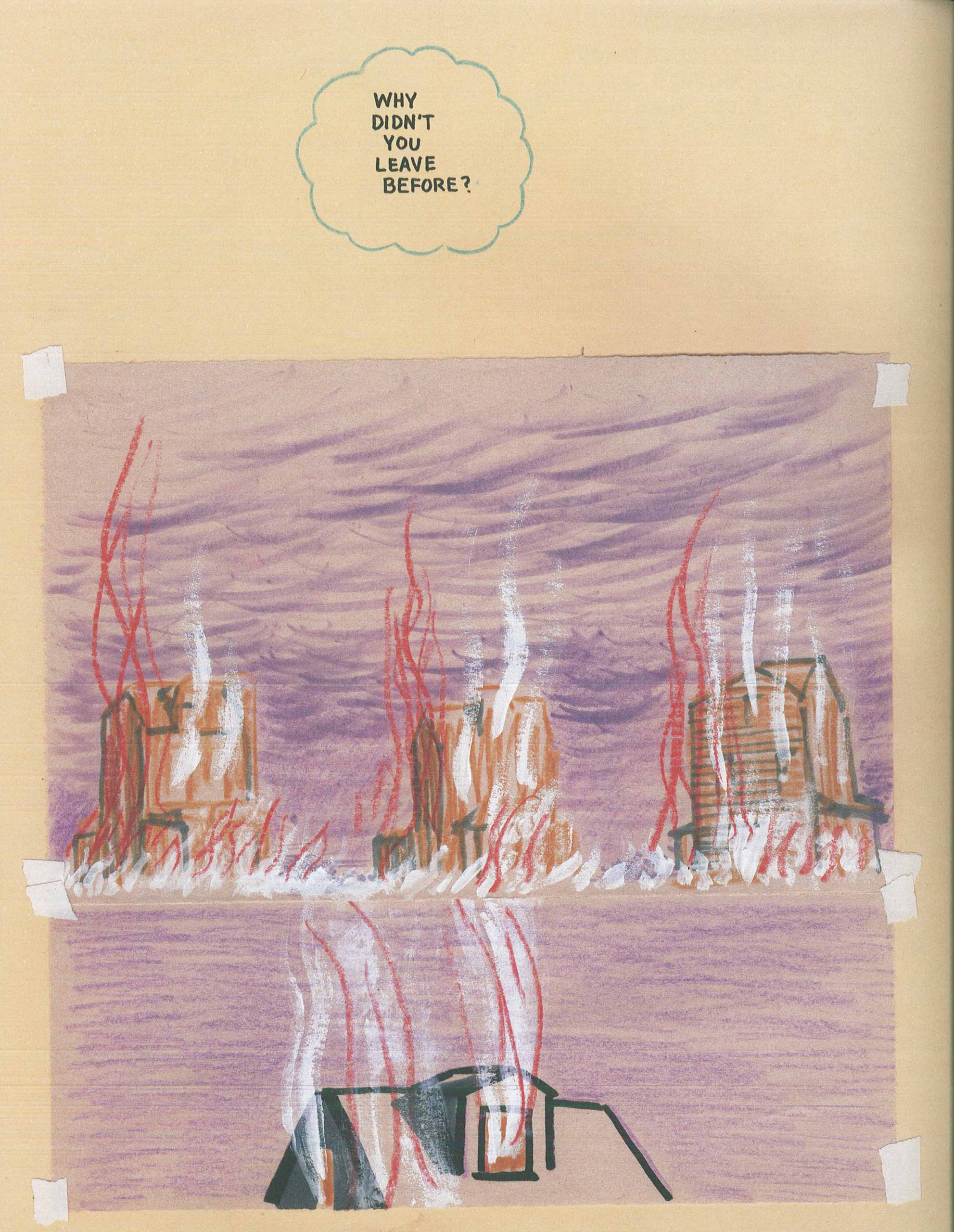

After a few more pages, however, Santoro pulls you into his memory dreamworld and you’re a goner. Memory really is this makeshift. Even big, heavy, seemingly solid structures—the steel on which Pittsburgh and much of our nation was built—won’t last forever, and as he tries and fails to piece his family’s competing stories into a coherent narrative, we see repeated drawings of falling, sinking, burning houses:

The basic premise of “Pittsburgh”: Santoro’s divorced parents haven’t spoken for years, and even after they recently got jobs at the same hospital, they still walk by each other in the hallways without saying a word. As if that isn’t enough animosity for an only child to work through, his mom’s health is failing. As Santoro explains in the opening, he began the book “to write a story for my mother, something to distract her while she got old,” but he “ended up writing the story for me, something to distract me while she got old.”

To highlight this work’s foundation of memory, impression, and emotion, in addition to the white tape that quite literally pieces his memories together, Santoro uses black lines and outlines sparingly:

As you might guess from the images so far, most of this book was drawn from memory, not from photographs, because, as Santoro explains in an interview on “Chimera Obscura,” he wanted to recreate emotional more than physical realities. “[T]he earliest memories that we have,” he says, “are maps of the rooms that we’re in, the spaces that we inhabit—those are some of our deepest memories . . . . I was really interested in the feeling I got when I was making those drawings.”

Other ways that Santoro strives to represent memory are to write “Pretzel barking” rather than “woof,” or in one case, to even tape a drawing of logs being sawed over a sleeping, ostensibly snoring, Pretzel. Santoro likens this technique to poetic structure, “rhyming” the images and creating atmosphere to help the reader’s senses and emotions “read” the story, more than their analytical brains.

Given such abstract goals, you won’t be surprised that Santoro has a background in fine art. He worked as an assistant for contemporary artists Francesco Clemente and Dorothea Rockburne. Santoro especially riffs on Rockburne’s use of color and mathematical structures. In his “Layout Workbook” series on “The Comics Journal,” he applies architectural and geometric theory to comics, analyzing Italian frescoes alongside the Hernandez brothers.

Yet Santoro is no snob, and he’s as generous with his knowledge as he is with his memories. He ran a correspondence course for years—decidedly not an online course, largely to keep it affordable—and more recently opened up a local studio, Rowhouse Residency, which he calls “a dojo for students much like a martial arts academy.” His background is more punk than aesthete, and he’s a champion of the do-it-yourself mindset that built the Pittsburgh comics scene—not to mention the Pittsburgh art scene, as nurtured by Andy Warhol before as well as after his move to New York City.

Is Santoro intimidated by Warhol’s legacy? “I love Warhol!” he told his interviewer on the “Boing Boing” podcast “RIYL” in 2017. “Warhol’s graphic techniques apply to all painting and all comics. . . . It’s a great gateway for a lot of people.”

The color explosion, the large panels, the blurred and/or offset lines: Santoro might work in a different genre than Warhol, but he’s definitely taken on his mantle when it comes to pop art and DIY craft like screen printing. (If you’re ever in Pittsburgh, check out the maker’s studio in the basement of the Warhol museum. It’s especially great for kids!)

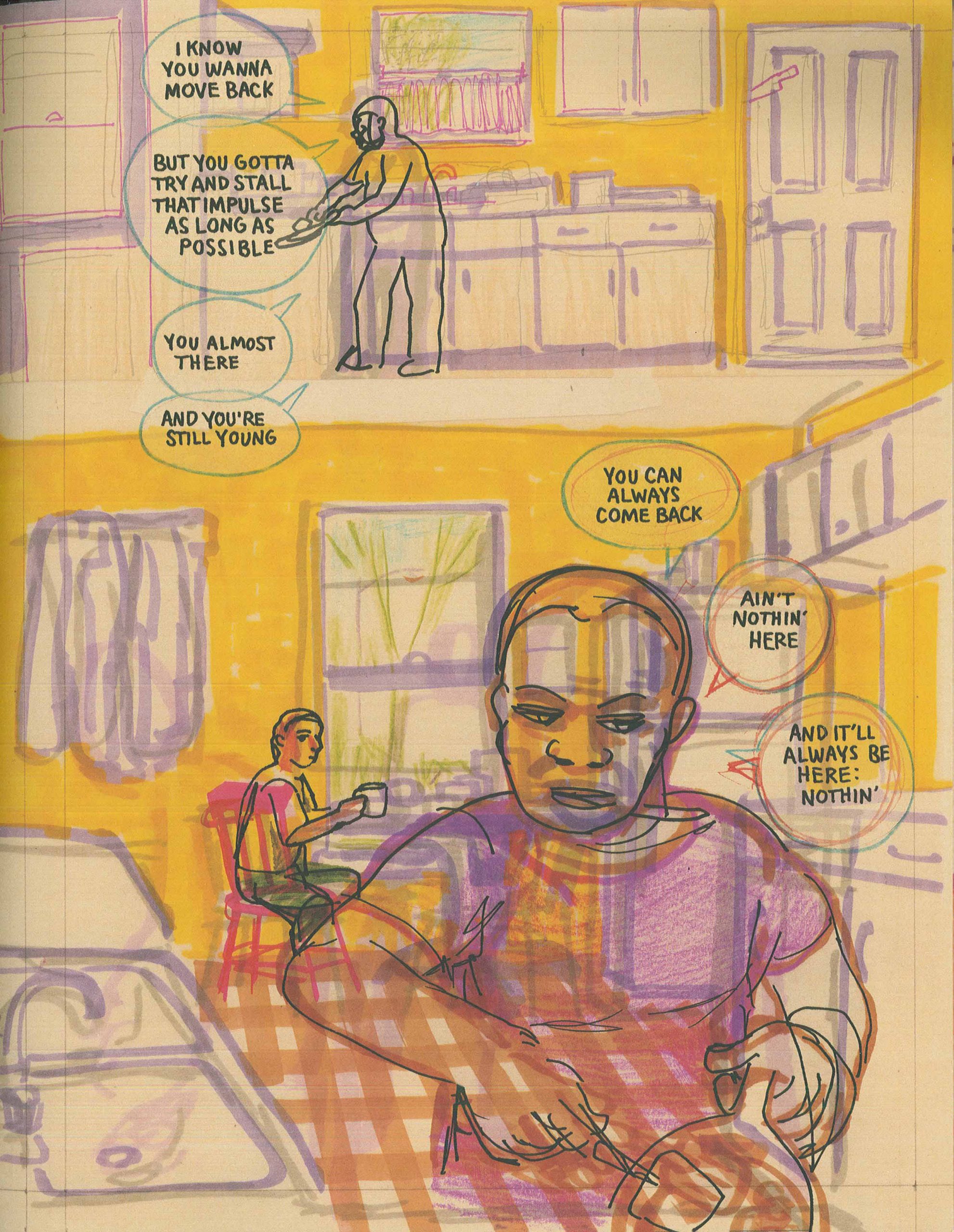

Also like Warhol, Santoro needed to leave Pittsburgh for a while, to take in new training and to get some perspective. In this memory, his godfather Denny encourages young Santoro to stay away as long as he can—to learn, yes, but also so Denny can live vicarously through him:

“I’m layering the crumbling and reconstruction of my family with the crumbling of Pittsburgh as I knew it and how it’s reconstructed itself,” Santoro recently told a “Comics Journal” interviewer.

Denny was right to encourage Santoro to stay away for a while, but fortunately, he was completely wrong in his assessment of Pittsburgh at hopeless. Rather than an homage to a dying city, this glorious book is a testament to how reconstruction comes not just from materials, but from people, neighborhoods, and shared memories worth preserving.

Great review!