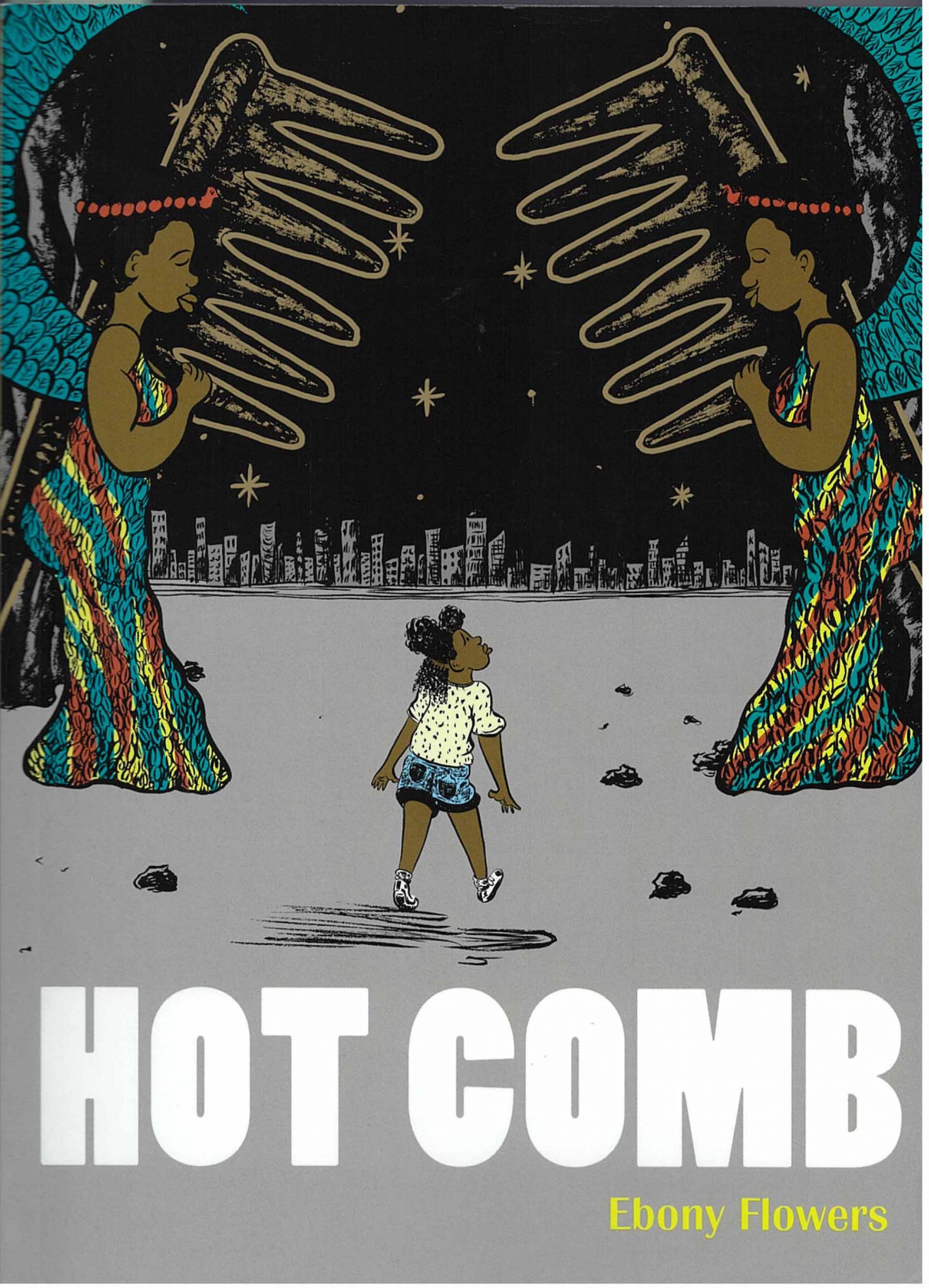

“Hot Comb” by Ebony Flowers. Drawn and Quarterly, June 18, 2019. 184 pp. Paperback, $22.95. Teen to adult.

Thanks to Fables Books, 215 South Main Street in downtown Goshen, Indiana, for providing Commons Comics with books to review. Visit the store or contact them at fablesbooks@gmail.com to find or order this or any book reviewed on this blog.

Quick note about upcoming workshops with comics artists I’ve reviewed: Frank Santoro, whose “Pittsburgh” I reviewed last month, will be giving a one-day free workshop in that city in March. And across the pond, Gabrielle Bell, whose “Everything Is Flammable” I reviewed in 2017, will be teaching a workshop in the French Pyrenees in June. That one’s not free, but surprisingly affordable given the setting, and scholarships are available.

With her debut “Hot Comb” topping “best of 2019” lists at outlets from “The Guardian” and “Publishers Weekly” to “Forbes,” you might think that Ebony Flowers must have been a kid prodigy doodling incessantly, making zines, and setting her sights on becoming a cartoonist. The real story is that she drew her first comic only eight years ago, in 2012, when she signed up for a class taught by comics grande dame Lynda Barry.

Flowers had just landed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison to pursue a Ph.D. in Curriculum and Instruction, and signed up for Barry’s class on a whim. She ended up writing and publishing sections of her dissertation in comics form. She now calls herself “cartoonist, ethnographer, teacher” on her website.

“Hot Comb,” a collection of short stories with a good dose of autobiographical content, reads nothing like a dissertation. As you might guess, all of the stories center on hair. “It’s hard for me to disentangle my experience as a black woman . . . in America from my experience with hair,” Flowers explained to the “Chicago Tribune.” The stories address stereotypes, microaggressions, and structural racism, but also joy, self-love, and the way hair can help forge positive bonds between women of color, especially black women.

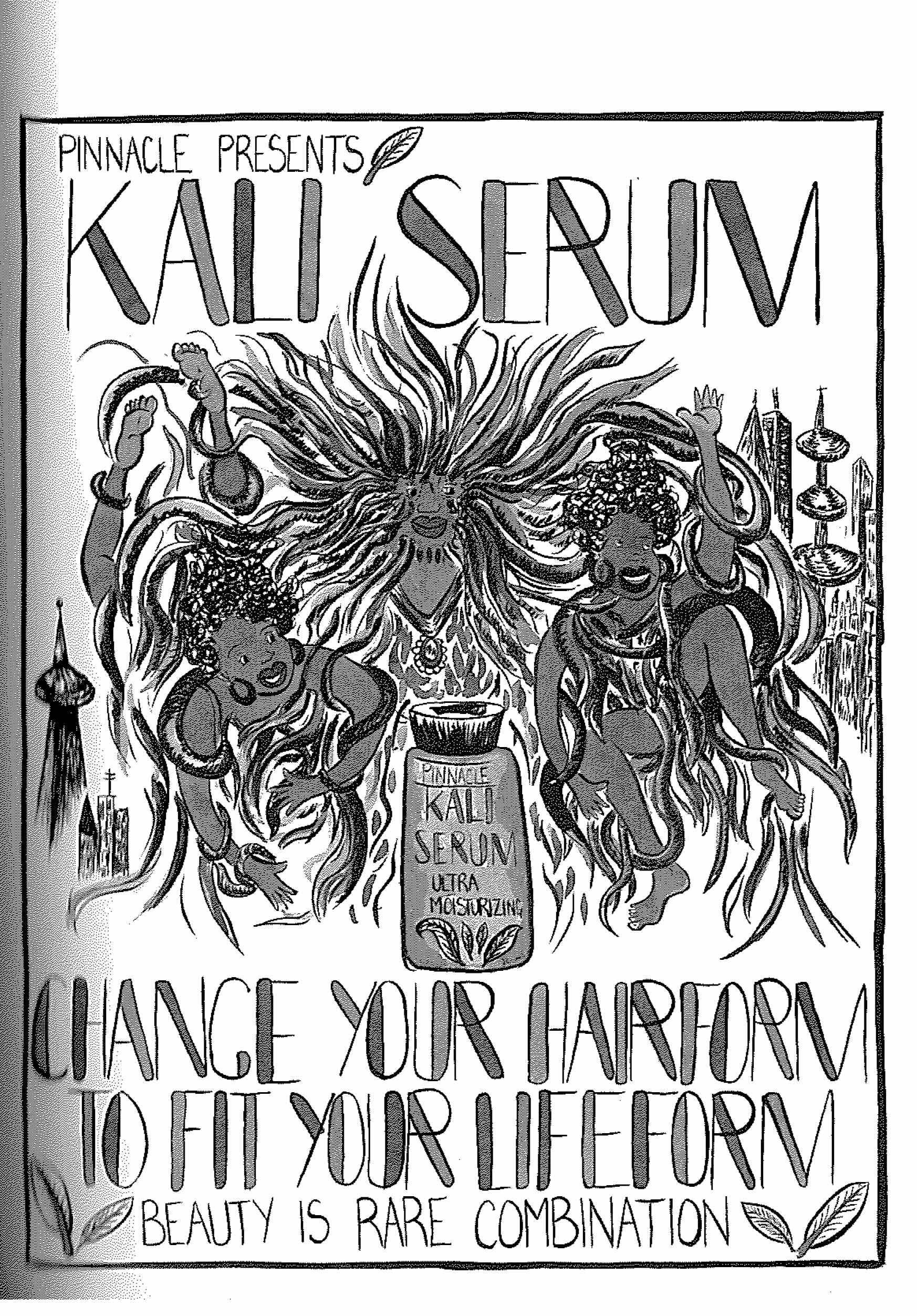

Flowers highlights that positive-negative tension in the segues between her stories, where she inks one-page parodies of the hair care advertisements that used to fascinate her as a child:

Under Flowers’ brush, the real-life brand “Summit” becomes “Pinnacle,” and other brands morph to “Pro-Aide” and “Kinky Mane.” One ad hawks regal “Lion King” and Black Panther themes, another spouts nonsensical promises of “DNA hydration.” Glorious more than insidious, these ads serve to both parody and honor, highlighting the complicated mix of pride and self-critique that has made black hair products profitable since at least the time of Madam CJ. Walker. “Through playful criticism,” Flowers explained to the “LA Review of Books,” “I’m conjuring up a future in which black women can be viewed as inspirational while loving their hair.”

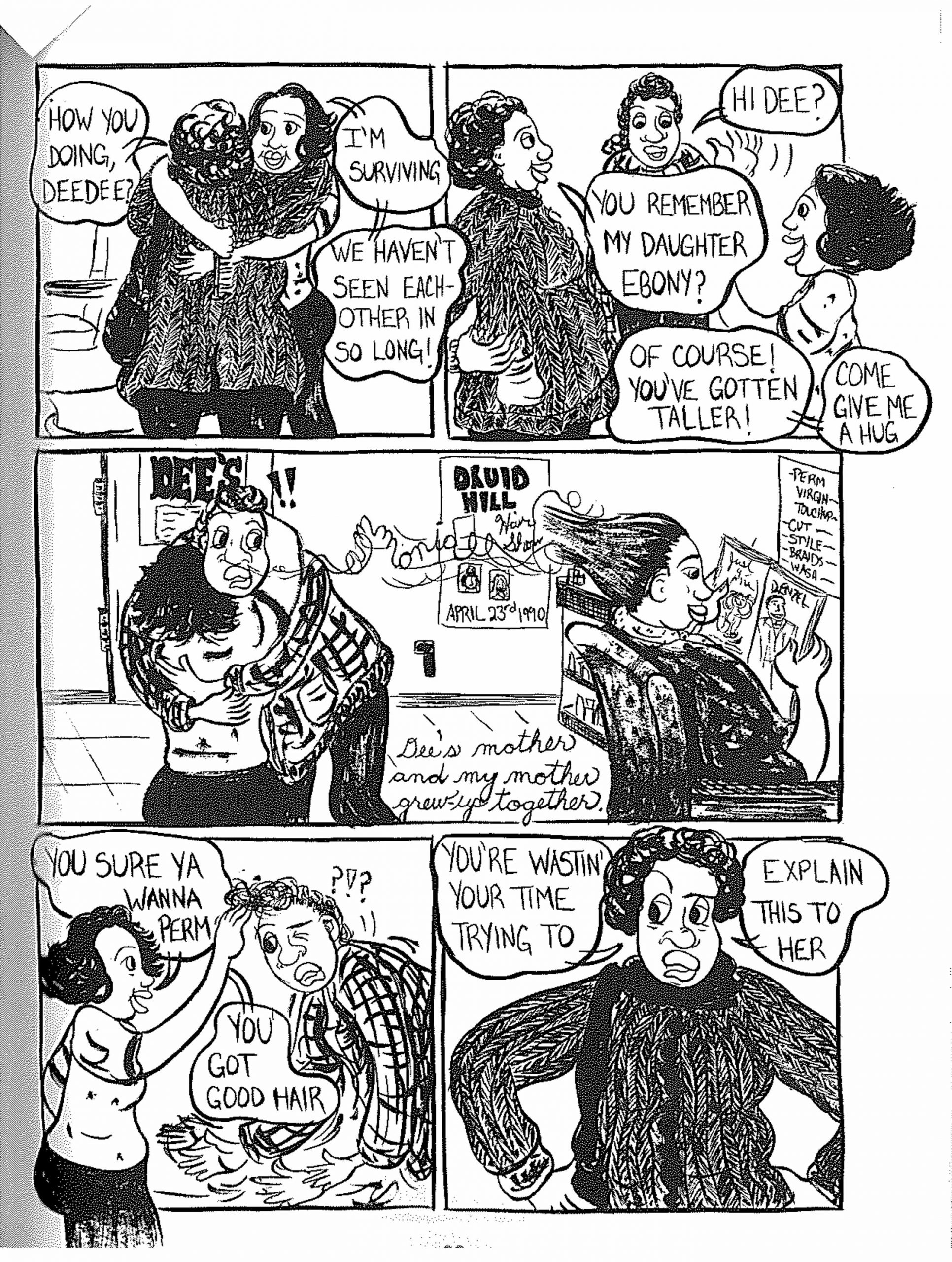

Those familiar with Lynda Barry’s work will see immediate visual connections between “Hot Comb” and the best qualities of Barry’s style: Flowers’ drawings value exuberance over fussy perfection, and revel in awkwardness within both the art and the narrative. See this page, for example, from the title story:

Characters—especially their hair and bodies—break out of panel boundaries, and the varied textures of not only hair, but also fabric and upholstery, are painstakingly feathered and crosshatched.

This page and this story highlight a multitude of comics’ unique possibilities, such as the ability to more viscerally convey all five of the senses, not just sight. Note, for example, that the scent of ammonia wafting between hair and nose in that long middle panel spells “ammonia” in tangled cursive, actively blurring the boundaries between text and texture.

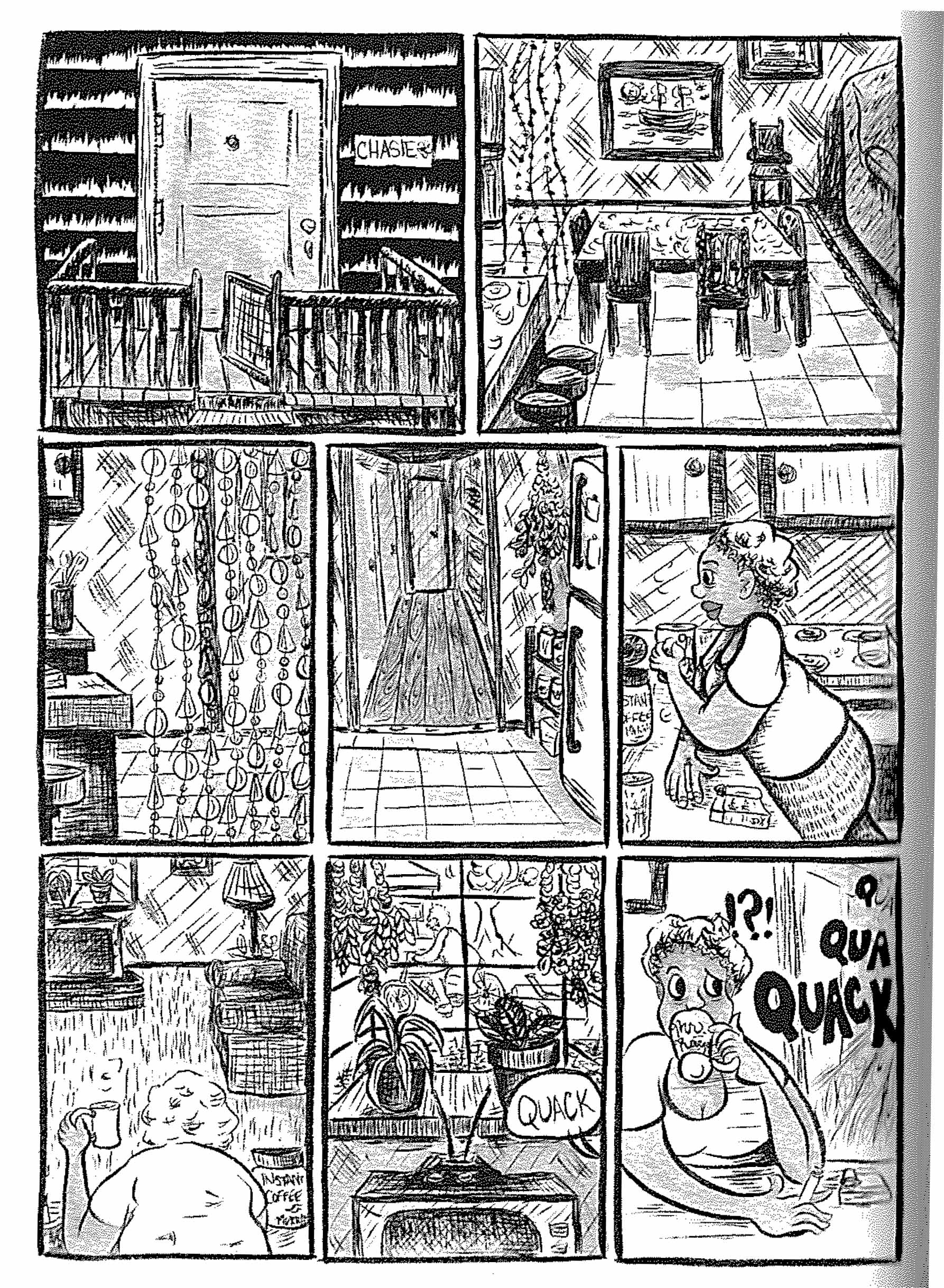

Visual texture is one of Flowers’ standout strengths. Her panels burst with contrast and pattern:

Every element of this page has a texture: the only true white spaces are a t-shirt sleeve and a kitchen floor tile or two. Lines run lengthwise, crosswise, and diagonal, the shading balanced rather than busy. The page as a whole contains a lot of visual sound, from the subtle click of the beaded curtain to the loud black “quacks” entering from the bottom right, enticing the reader to turn the page. Any parent or caretaker who treasures a few spare moments of restful silence will be able to relate: it’s as if the visual textures cushion and protect the mom’s brief page of peace.

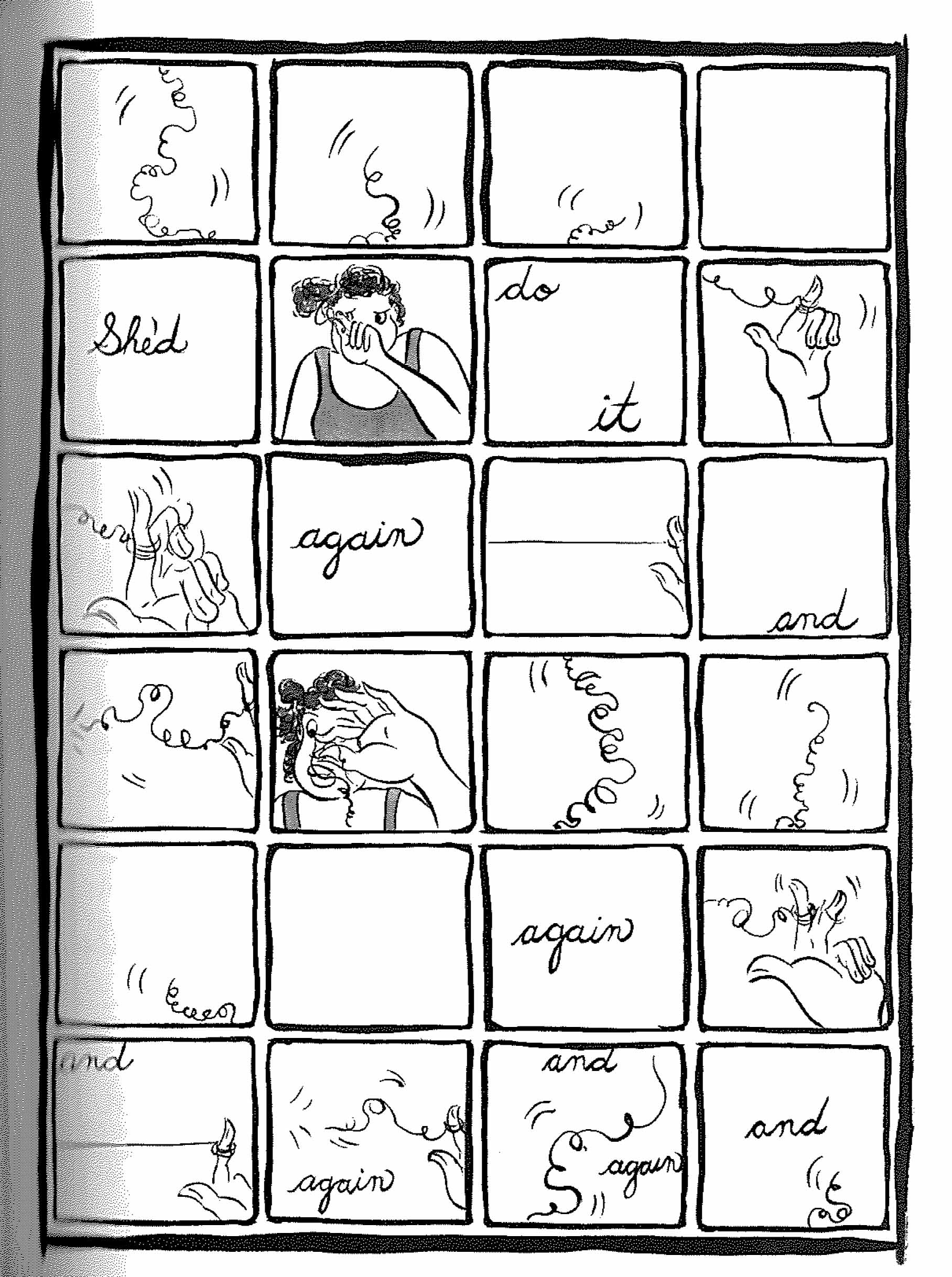

Flowers also varies her panel size and progression. “My Lil Sister Lena,” a story about the only black girl on an all-white softball team, holds one of the best examples of her dynamic panels. In this sequence highlighting the sister’s obsessive-compulsive hair pulling (trichotillomania), which is triggered by the team’s unwanted fascination with Lena’s hair, there are no repeats in angle or perspective, despite the uncharacteristically high number of panels in this 24-panel grid. Every panel moves the story forward, even the two blank ones:

“‘Hot Comb’ will be a mirror for some people and a window for others,” Flowers has told more than one of her interviewers. “Growing up, I loved getting my hair done by my mother,” she told the “LA Review of Books.” “It was our special time together. She was the mother of three children and worked two jobs. I treasured sitting with her on Sunday afternoons while getting my hair braided.” Many of the characters in the book share secrets and rambling stories while doing each other’s hair. Of course hair is about identity, and sometimes vanity, but “Hot Comb” highlights how it can also be about paying attention, showing love not through words, but by spending time being fully present with another human being.