“Spring Rain: A Graphic Memoir of Love, Madness, and Revolutions,” by Andy Warner. St. Martin’s/Griffin, January 28, 2020. 208 pp. Paperback, $19.95. Adult.

Thanks to Fables Books, 215 South Main Street in downtown Goshen, Indiana, for providing Commons Comics with books to review. Visit the store or contact them at fablesbooks@gmail.com to find or order this or any book reviewed on this blog.

Note: St. Martin’s/Griffin Books sent me a free copy of this book.

Andy Warner opens his new memoir “Spring Rain” with a disclaimer: “Memory is a tricky business.” We watch his plane fly into Beirut, Lebanon, and see his younger self make his way through customs and the airport. It’s 2005, he’s twenty-one, and he’s visiting Beirut as an American study-abroad student. Present-day Warner explains that he’s been reading through old diaries from his semester abroad to piece together the time in his life that we’re watching and reading. “It’s hard to reread,” he admits. “I come off like an idiot.”

It’s a brilliant opener for two reasons. First, for Warner’s disarming self-deprecation, which encourages readers to trust him. Second, for the narrative teaser: we’re waiting for young Andy to do something stupid, so that we can find out precisely what form his idiocy will take.

Given Warner’s current professional persona, it’s difficult to imagine him acting idiotic at all. Warner is a contributing editor of the comics-only satire, non-fiction, and political journalism magazine “The Nib.” His brief pieces from there and elsewhere (“Salon” and “Buzzfeed,” among many others) have been collected into two books, “Brief Histories of Everyday Objects” from 2016, and more recently, “This Land Is My Land” (2019), about self-made countries and intentional communities, which features art by Sofie Dam.

The “journalism and nonfiction” tab on Warner’s home page showcases what comics can accomplish for journalism that purely word-based writing cannot, and spans an impressive array of topics: international crisis spots like in Kashmir, South Sudan, and North Korea, for example, as well as news topics closer to home, such as a healthcare crisis in Puerto Rico and the recent evisceration of the Voting Rights Act.

Comics journalism was largely pioneered by Joe Sacco, one of Warner’s idols. (If you’re not familiar with Sacco’s work, you can read my review of his book “The Great War” for an overview.) Warner’s style and subject matter, however, are much more playful than Sacco’s. As he told an interviewer for “The Silver Sprocket” back in 2016, “It’s sort of hard to get a grasp on what I do sometimes. . . . I think the thing that ties it all together is that it’s stuff that interests me, that I can really dig deep into. Oddly, that includes both the Syrian refugee crisis and the history of the toothbrush.”

“Spring Rain,” however, is more memoir than journalism, more serious than playful, and, most important to note, more about Warner than about Beirut itself. I’ve seen it categorized as “travel literature,” which is a mistake. Warner is very clear that this is a book about how NOT to travel in Lebanon—especially when, as he writes in the opening pages, “In the space of three months, the former prime minister was assassinated in a massive car bomb, the government fell, and I lost my mind.”

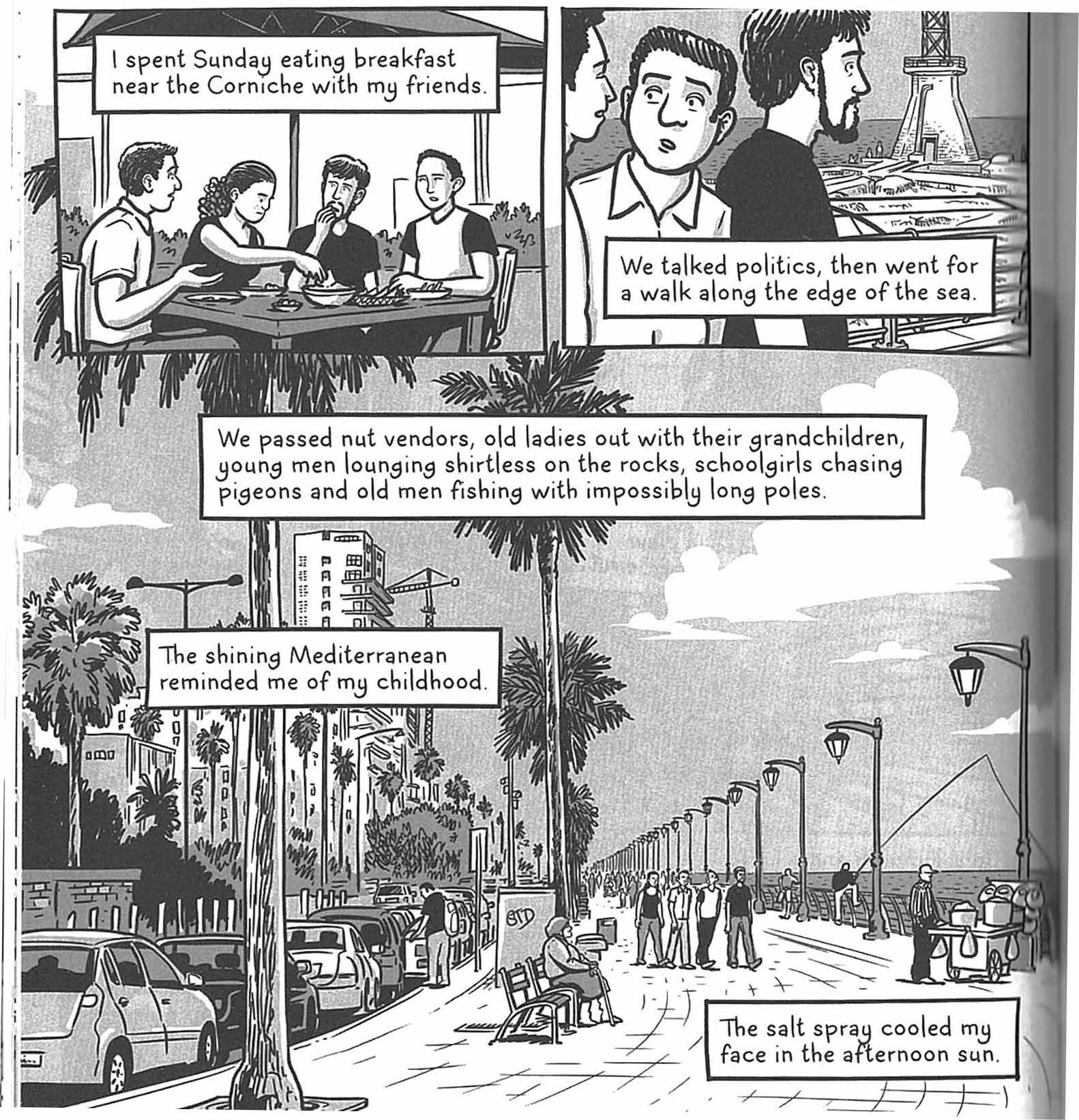

That said, this book nevertheless provides a rare and unique window into Beirut at an unstable time. Warner complicates and humanizes the US’s standard news clips about Lebanon as a violent country always at war. In contrast, Warner frequently highlights the beauty of the city, its surrounding countryside, and its people. The waterfront, for example, is stunning:

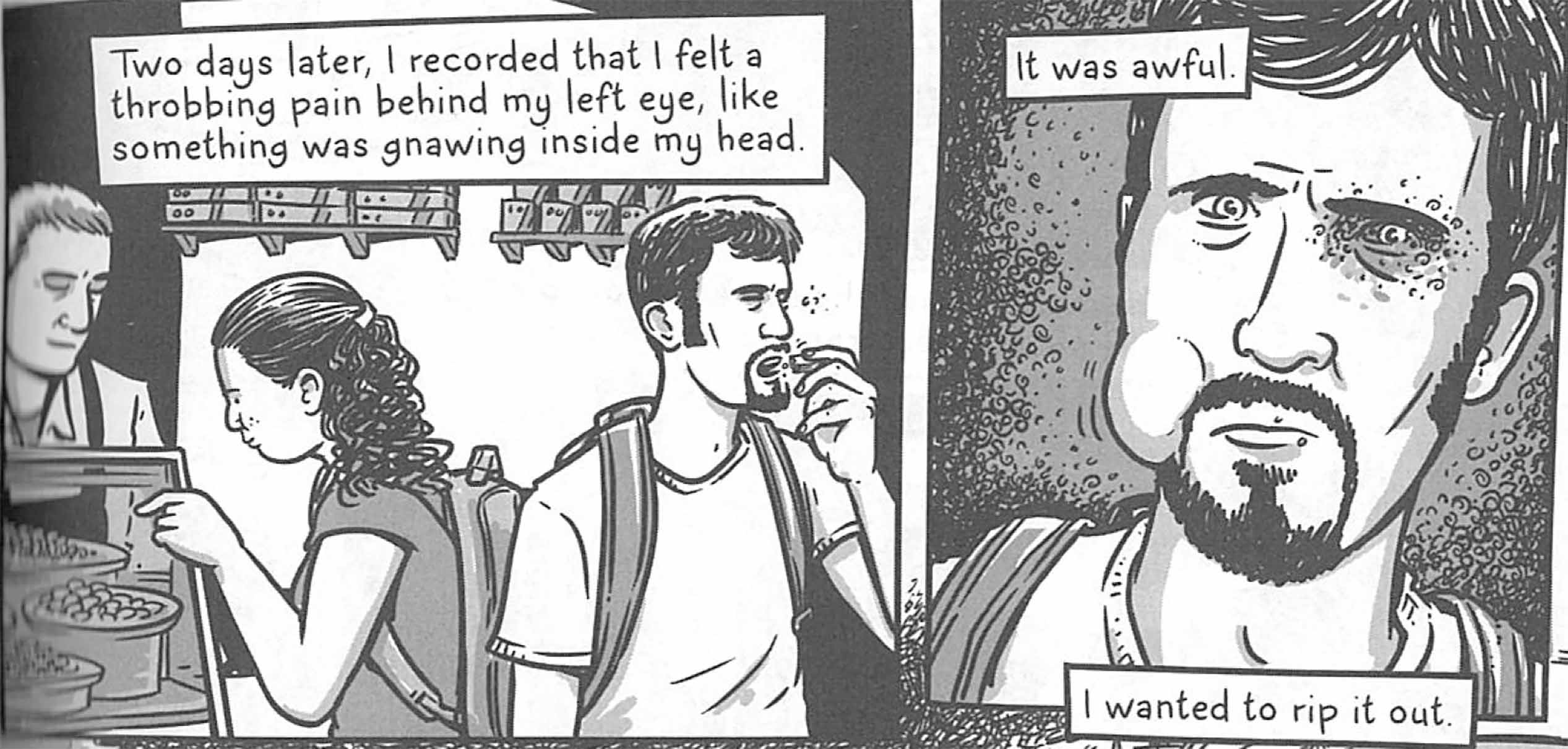

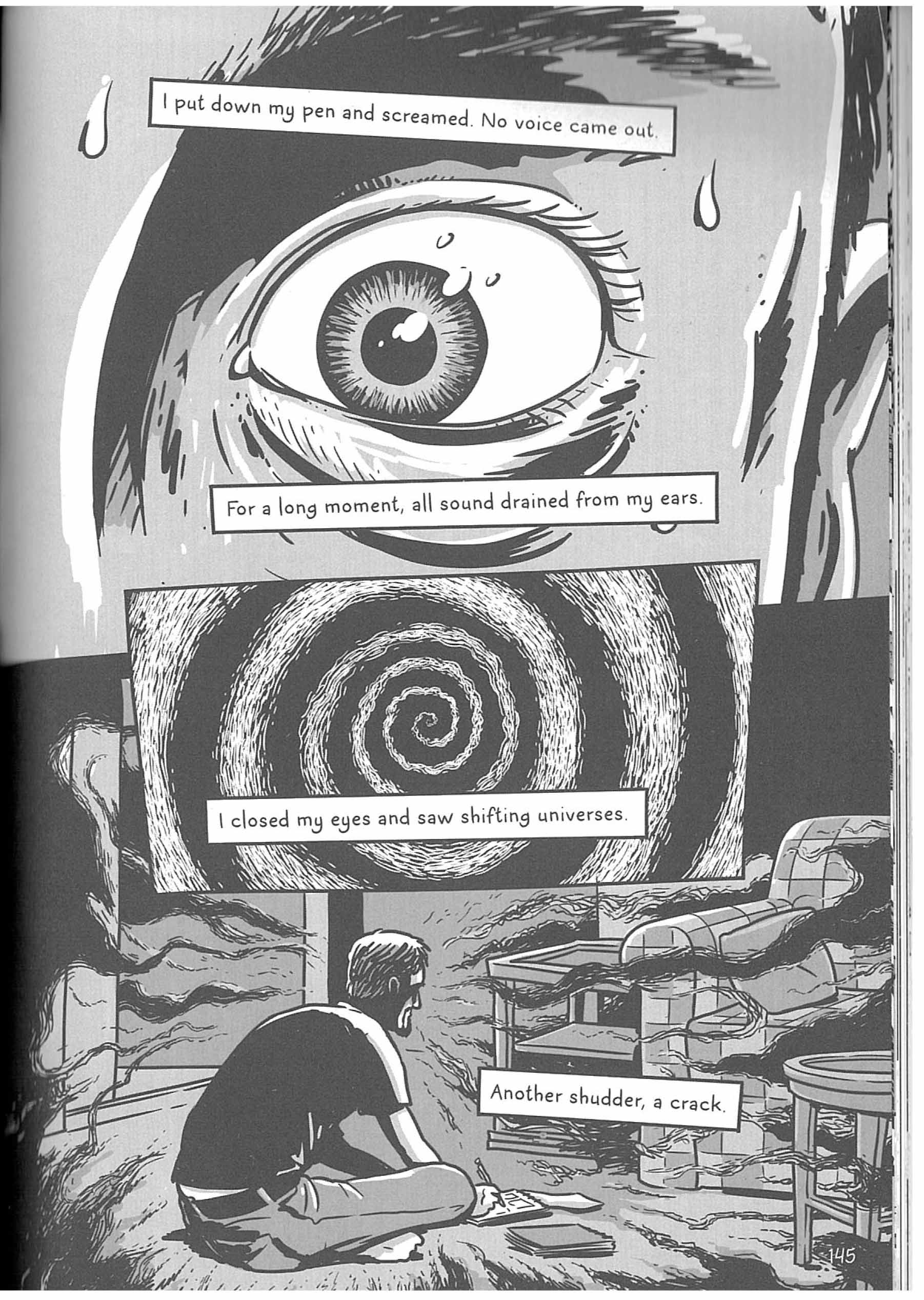

If you find yourself wanting to dig deeper into Beirut’s current political situation, that’s for a different story, and “The Nib” has got you covered in a recent piece co-written by two Middle Eastern journalists. “Spring Rain,” however, is a memoir, not a work of journalism, and its main goal is to tell the story of young Andy’s spiral into mental illness. As the book progresses, we see Beirut filtered through the warped lens of Andy’s brain, which makes his head feel like this,

and even leads him into paranoid hallucinations that someone who looks like this

is following him.

One of the main ways that young Andy pulls through his mental struggles is by continuing to create: we see him drawing even when his nightmares make their way into his reality, even when his head and body are buzzing so intensely that he draws himself with what looks like a giant black cloud of flies spiraling up from his head. As he told “Silver Sprocket,” he even kept drawing when, two years after this trip, he had a serious bike accident and broke his arm in three places: “I learned digital tools to be able to draw with my left hand while I was still in the cast.”

Many comics purists disdain purely digital composition like Warner’s in “Spring Rain.” If you’re open to being convinced of the possibilities of digital comics, however, Warner is a good advocate for what the tools of that genre can accomplish. Take this page, for example, which illustrates the breakdown reaching its peak.

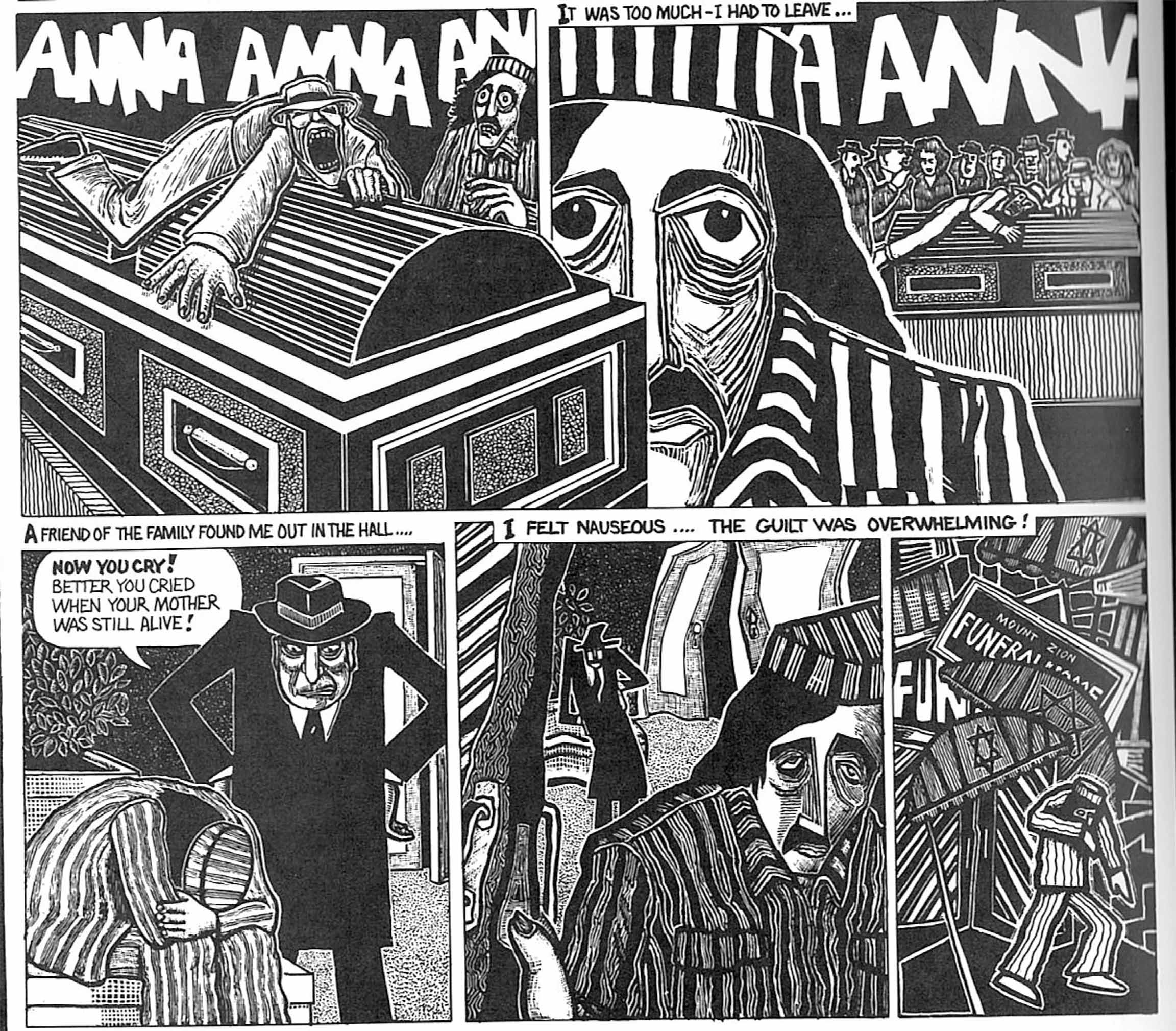

Aficionados are likely to be reminded here of another famous breakdown in comics, that of young Art Spiegelman in “Prisoner on Hell Planet,” originally an underground mini-comic, which was then incorporated into Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book “Maus.”

Digital comics aren’t lesser, just different. Spiegelman’s hand-drawn panels qualify as high art, a la the German Expressionist film masterpiece “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari,” and the panels’ distortion and claustrophobia almost viscerally recreate young Art’s mental struggles in his readers.

Warner, in contrast, is more concerned with explaining, step by step, how it feels to have a breakdown—and that’s exactly what his streamlined page and panel composition accomplish.

Warner’s wheelhouse is short, informative pieces, and for readers accustomed to these nonfiction nuggets, “Spring Rain” might feel rambly—but this book’s circuitous narrative makes it all the more honest. This was a time in Warner’s life that didn’t fit into a neat narrative package. We get to watch young Andy make plenty of mistakes—especially when it comes to recreational drugs that (obviously) don’t mix well with mental illness. We also get to witness him exploring his sexuality, as well as, more generally, his early twenties, a time overflowing simultaneously with possibility and with triggering confusion, even without the added complications of a fragmenting city and a fragmenting mental state.

Warner told the podcast “Deconstructing Comics” in 2015 that “problem-solving” is a large part of what draws him to create nonfiction comics. “You’re falling into this new world, and trying to find a pathway through it, to show it to somebody else.”

He’s especially excited by the new voices who are similarly committed to this form of nonfiction storytelling, so that readers can learn about even more “new worlds.” After teaching for the first time in 2015, Warner gushed, “The majority of my students were female. And that’s huge” for a field historically dominated by white men like himself. “Women, people of color, and young [people]—and they’re coming up. . . . What’s exciting to me is not necessarily how the form will change, but how the people using that form will change. . . . We’re on a positive trajectory,” he adds, and as readers and citizens of a troubled world, we’re all fortunate that Warner, even in the midst of crisis so many years ago, was heading in the right direction as well.