“The Man Without Talent,” by Yoshiharu Tsuge. New York Review Comics, February 2020. 240 pp. Paperback, $22.95. Adult.

Thanks to Fables Books, 215 South Main Street in downtown Goshen, Indiana, for providing Commons Comics with books to review.

COVID-19 UPDATE: Please help your local small businesses stay afloat! At the time of this post (Tuesday 3/24), you can still order books from Fables and arrange to pick them up curbside or have them delivered. Contact the store at fablesbooks@gmail.com or call (574) 534-1984 to order.

If you can afford it right now, you can also support Fables and Goshen’s other downtown small businesses by ordering gift certificates from them now, and then going on a big spree later on, when we’re all allowed out of the house again.

Note: New York Review Comics sent me a free copy of this book.

Contrary to the title of “The Man Without Talent,” Sukezo Sukegawa, the book’s main character, is exceptionally talented. His problem—which becomes the problem of his wife and young son as well—is that he insists on starting his own business in an entirely different field. If Suzeko lacks talent, it’s as an entrepreneur, not an artist. He and his family live in poverty as he tries and mostly fails to sell attractive found stones, old cameras, and other assorted junk. When he visits his local bookstore, however, the bookseller practically begs him to write more comics. His wife does too—not out of love for his comics, but out of desperation.

Witnessing Sukegawa and his family negotiate his aimlessness can be, at times, sad and frustrating. This guy is maddening: he refuses to act as the “hero” of the story, which likewise refuses the narrative a standard trajectory.

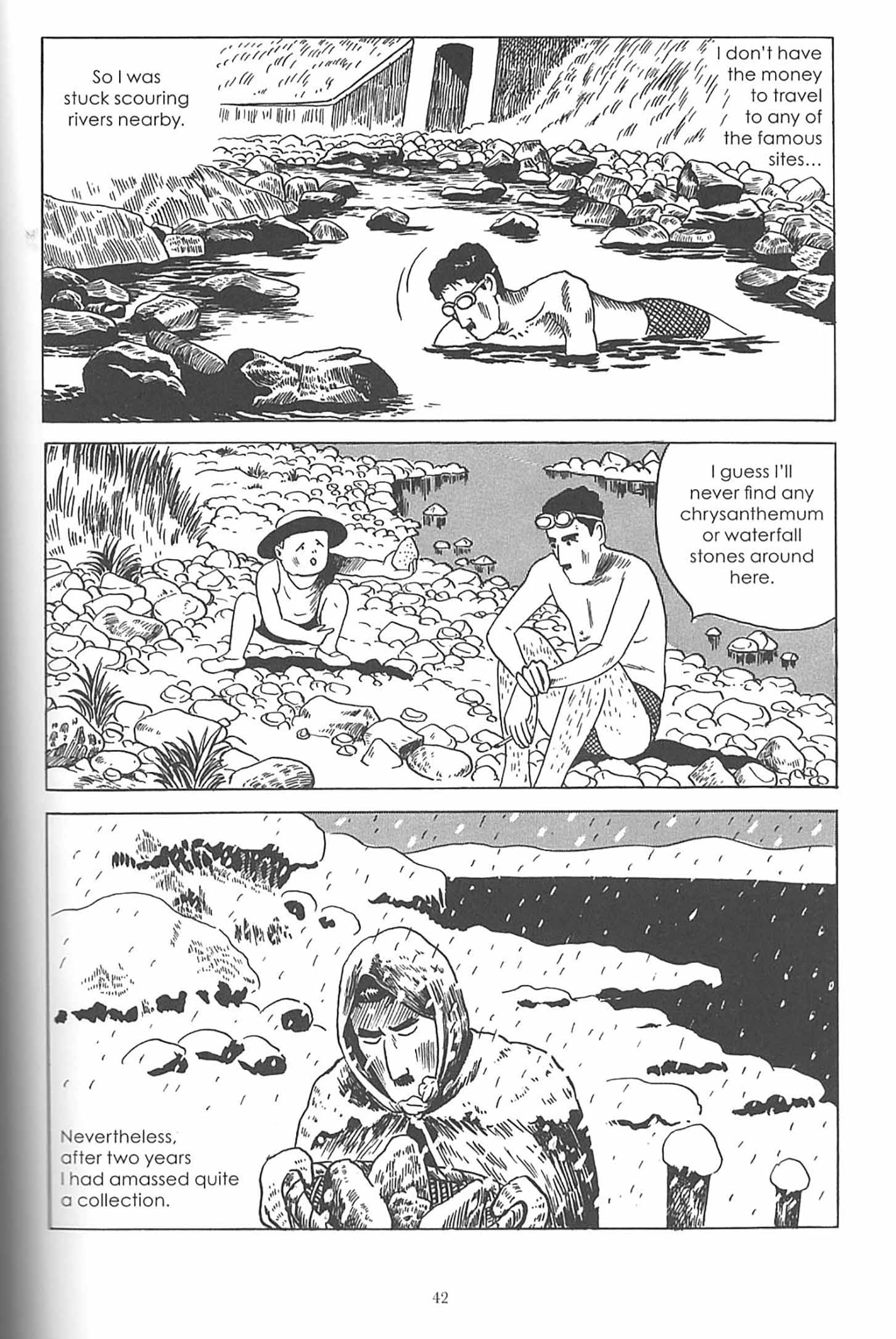

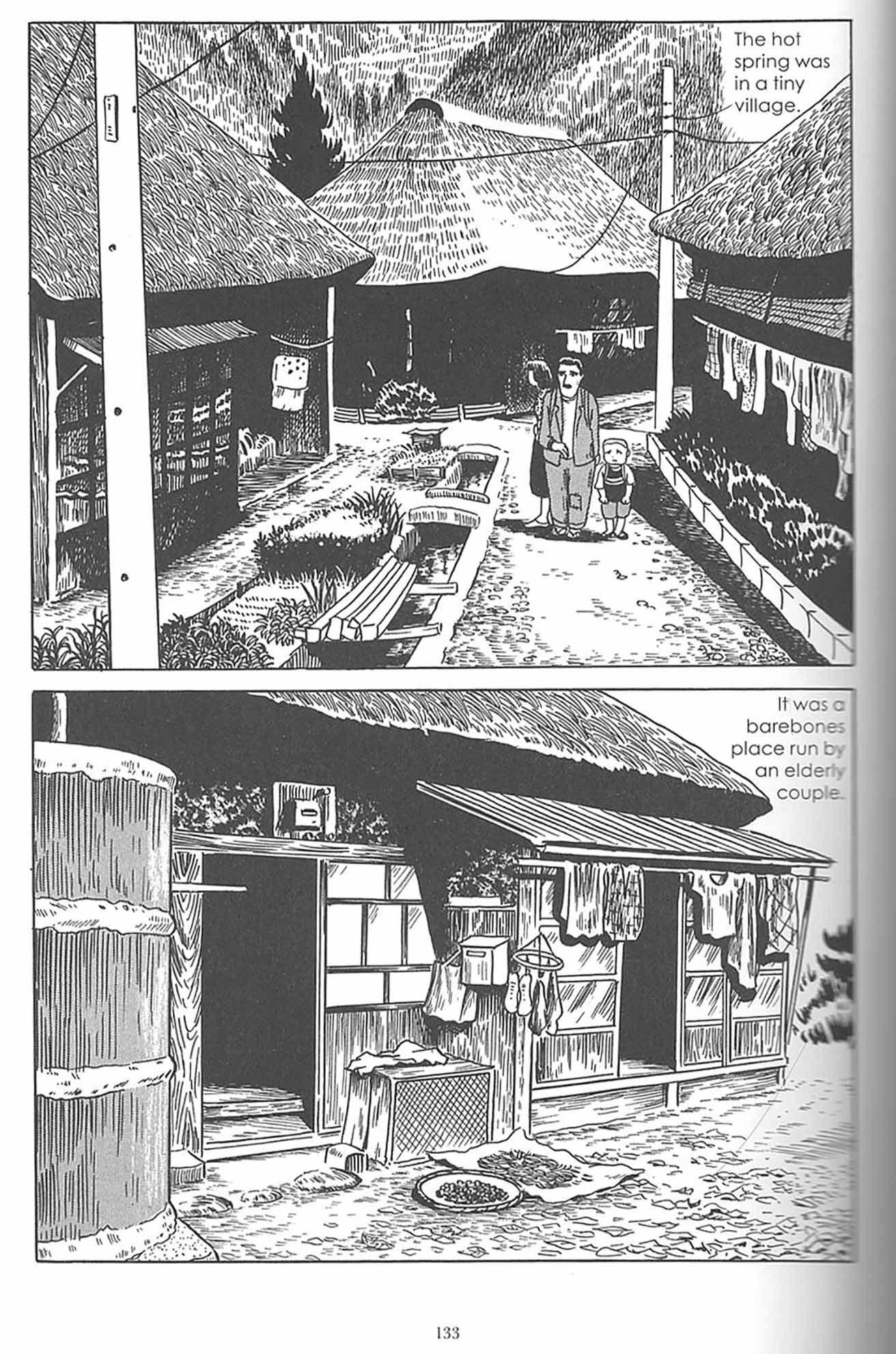

Part of the story’s point, however, as you soon figure out, is the failures of its inert protagonist—although, fortunately, there’s also more to the book than that. Much like the work of Frank Santoro, Seth, or John Porcellino, “The Man Without Talent” will slow you down as it repeatedly rejects your expectations—you can’t speed from one plot milestone to the next. Once you give in and let the book shift you into a lower gear, however, the level of detail in the landscape is a reward in itself:

“The Man Without Talent” is comics artist Yoshiharu Tsuge’s first full-length English-language translation; the book was first serialized in the Japanese magazine called “Comic Baku” from 1986-7. Tsuge hasn’t published a new comic—or manga, as they’re called in Japan—since then. Unlike his protagonist, however, Tsuge has made enough from his comics and their subsequent film rights to live quite comfortably.

Nevertheless, fans have been begging Tsuge for more, much like the bookseller in the story. Even though Tsuge hasn’t published new material in over 30 years, he just received an award to a standing ovation at Europe’s top comics festival, Angouleme. Fans are hoping that this is only the first of many more translations of his work.

While manga for kids, especially teens, is a major industry in the US and much of the West, manga for adults has always been a harder sell—especially manga like Tsuge’s, with more artistic, expectation-busting goals. Manga translations themselves raise logistical challenges that most English-language publishers would rather not deal with: the books read what seems like “backwards”: from the back cover to the front, and from right to left on each page.

In addition, manga lettering is integral to its page composition, and is worked into the visual atmosphere more than most comics in English. Here’s an example from the original Japanese-language version of the series “Sunny,” by Taiyo Matsumoto. (See my 2014 review here.)

In the English-language translation, the publisher (Viz Media) did its best to replicate that effect by hiring an artist to hand-letter:

Unlike an entirely word-based literary translation, then, a manga translation can become a logistical headache. The hand-lettering maintains the words-as-landscape effects of the original Japanese version—but this work can also be labor-intensive and expensive for a small-market “art” book.

This translation of “The Man Without Talent” does use a digital font rather than hand-lettered text. Initially, the choice feels jarring, at odds with its meticulously illustrated surroundings. If you can get used to reading the panels right to left, however, you can also get used to the typed lettering—and once Tsuge pulls you into his world, you won’t notice much besides the rich and exquisite details:

Much like the best haiku direct readers’ attention to the world around them rather than to the poem’s own construction, this book’s landscapes, and the people making their way through them, ultimately prove more important than the words.

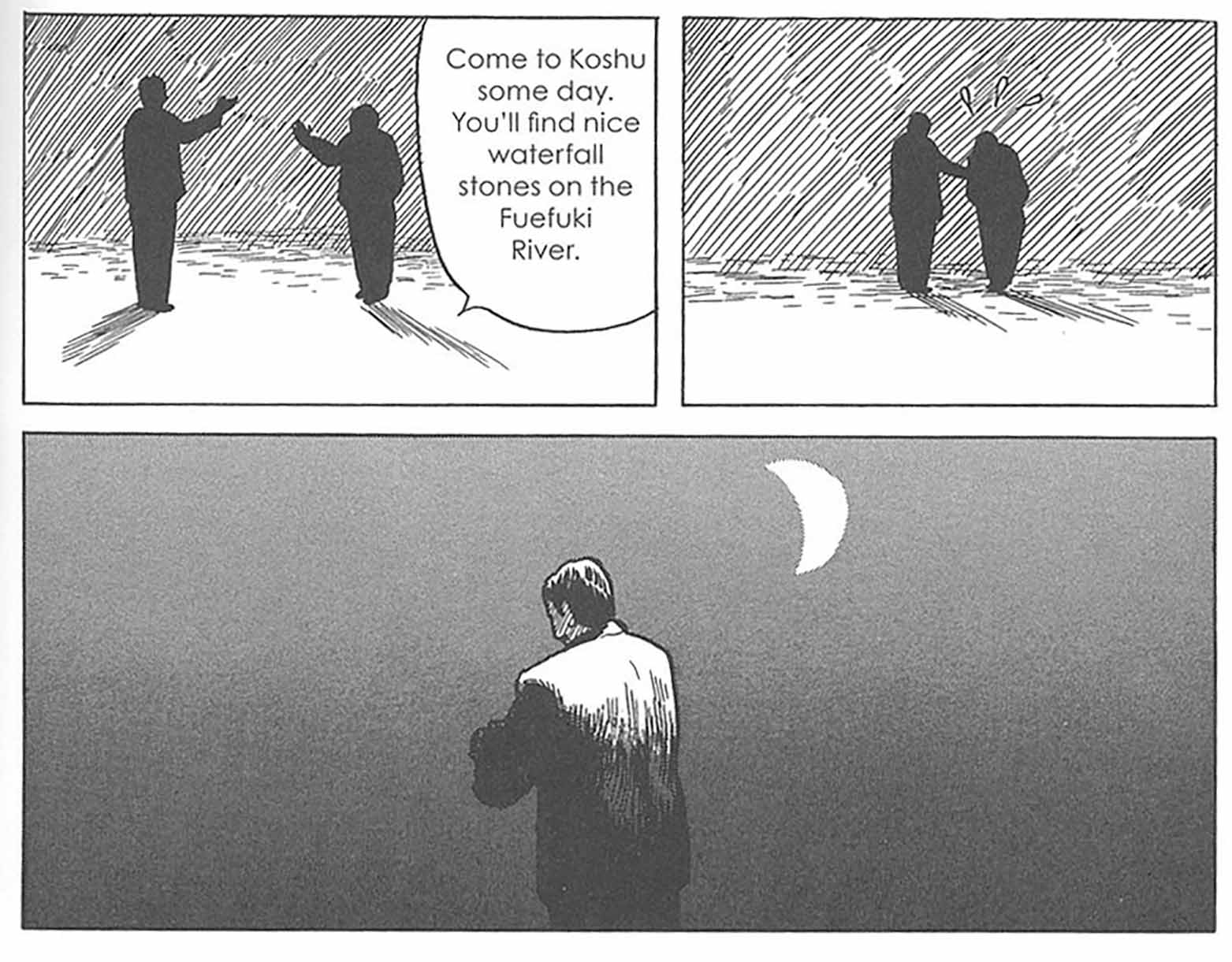

This prioritization of space and the people within it translates to the book’s less detailed illustrations, too—like this one, in which Sukegawa finds himself unexpectedly comforting an acquaintance:

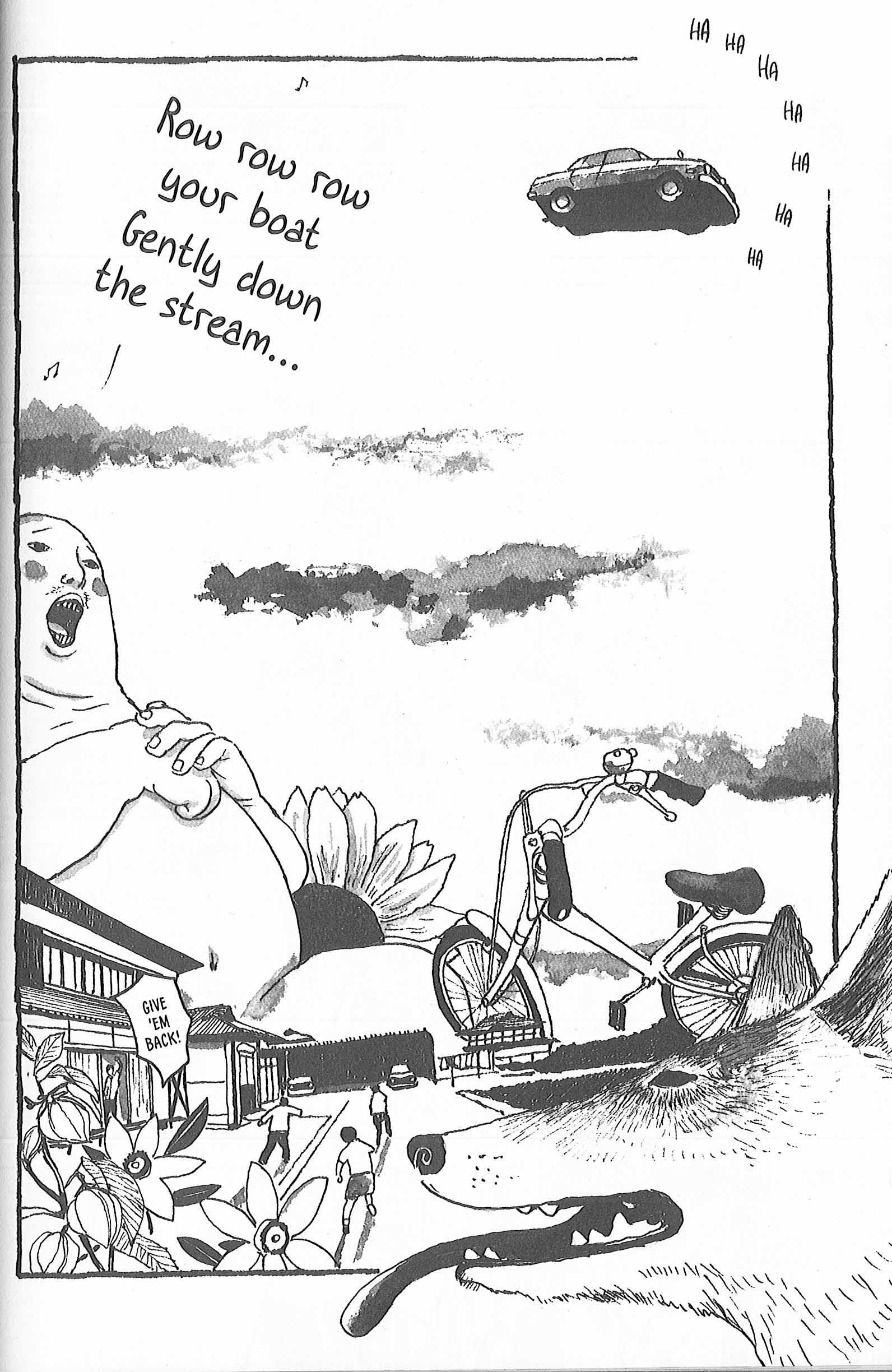

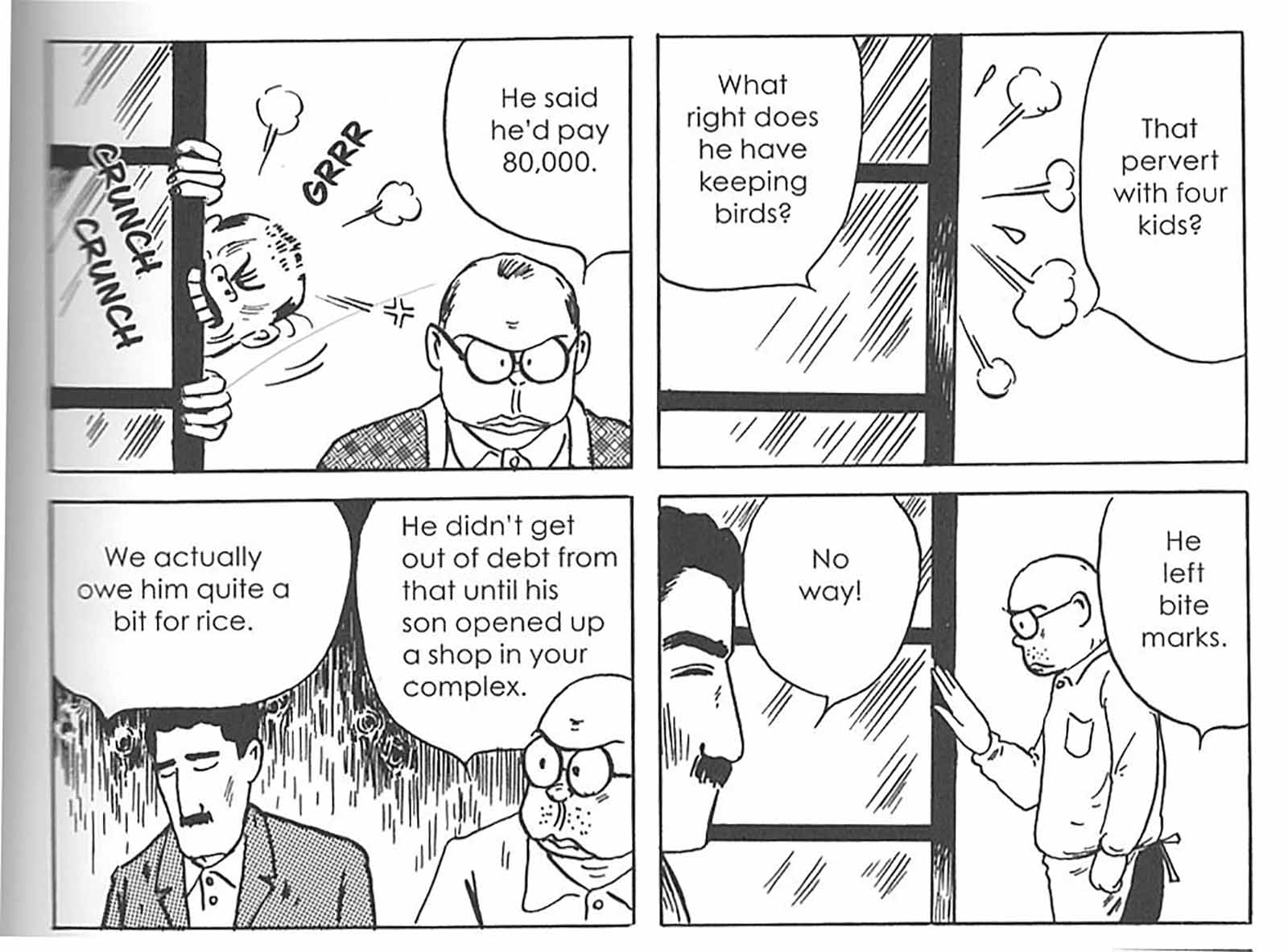

It’s not at all a surprise that this book’s back-cover blurb is by Chris Ware, whose recent work “Rusty Brown” likewise threatens, at times, to prove more depressing than rewarding. Much like Ware, however, Tsuge expertly pulls readers back from the brink just in time, in this instance with humor:

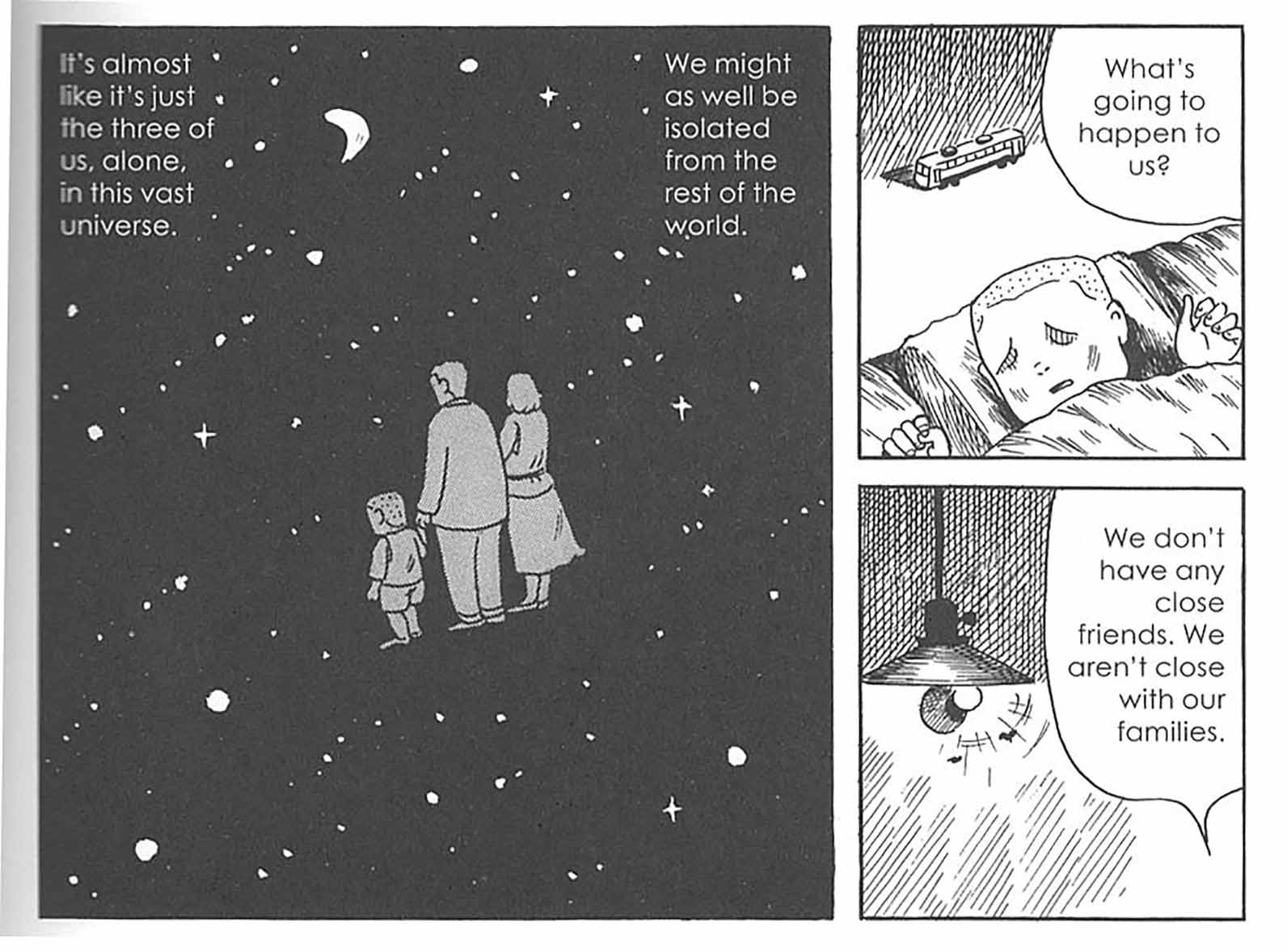

Tsuge’s work repeatedly shifts from serious to slapstick, from despair to hope. Here, for instance, Sukegawa and his family attempt to go on vacation, but seem at first to fail even at recreation, as their trip goes awry step by painful step. Yet the family’s fights and frustrations eventually give way to this moment:

It’s no spoiler in a book like this to tell you that they do make it to the other side of this moment of despair: the family’s there for each other, even on the verge of disaster. The journey isn’t easy, and it’s often not fun, but they do make it. If they can do it—especially with such a spectacularly “talentless” head of household—then maybe we can too.